Rubric-Based Rewards for RL

Extending the benefits of large-scale RL training to non-verifiable domains...

Many of the recent capability gains in large language models (LLMs) have been a product of advancements in reinforcement learning (RL). In particular, RL with verifiable rewards (RLVR) has drastically improved LLM capabilities by using rules-based, deterministic correctness checks (e.g., passing the test cases for a coding problem) as a reward signal. Deterministic verifiers allow RLVR to provide a reliable reward signal that is more difficult to exploit compared to the neural reward models that were traditionally used for RL with LLMs. Such improved reliability has made stable RL training possible at scale, enabling the creation of powerful reasoning models with extensive RL training. Despite these benefits, verifiable rewards also have limitations—the same properties that make RLVR reliable confine it to domains with clean, automatically-checkable outcomes.

“While lots of efforts have been paid on RLVR, many high-value applications of LLMs, such as long-form question answering, general helpfulness, operate in inherently subjective domains where correctness cannot be sufficiently captured by binary signals.” - from [3]

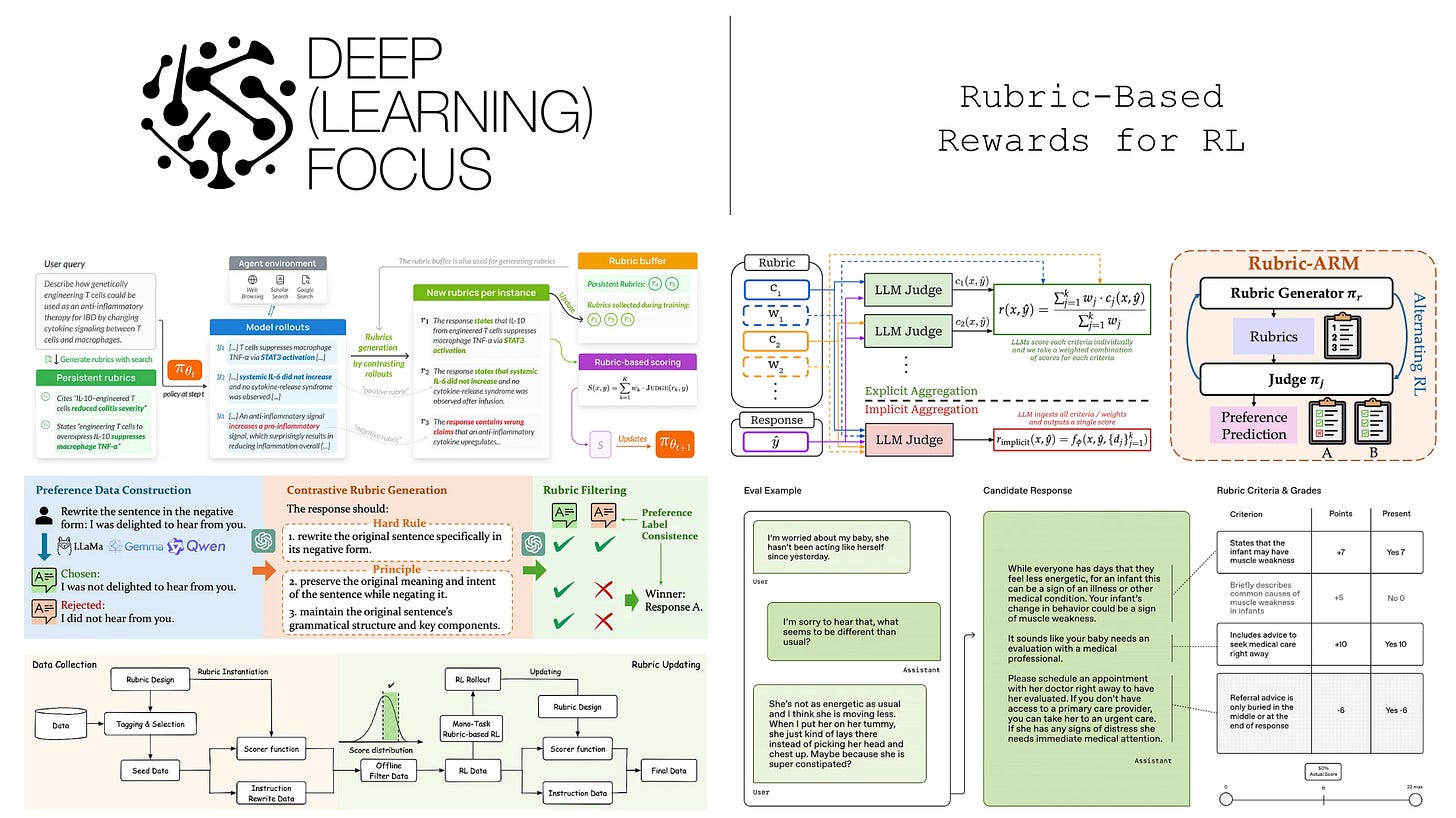

Many important applications (e.g., creative writing or scientific reasoning) are not verifiable, making RLVR difficult to apply directly. To address this gap, we need reward signals that preserve RLVR’s scalability and reliability while still working in non-verifiable settings. Rubric-based rewards are a promising step in this direction: they decompose desired model behavior into structured, interpretable criteria that an LLM judge can evaluate and aggregate into a multi-dimensional reward. By creating prompt-specific rubrics that specify the evaluation process in detail, we can derive a more reliable reward signal from LLM judges and, therefore, use RL training to improve model capabilities even in highly subjective domains. For this reason, rubric-based RL training, which we will cover extensively in this overview, has become one of the most popular topics in current AI research.

From LLM-as-a-Judge to Rubrics

Before learning about how rubrics can be used for RL training, we need to build a background understanding of LLM-as-a-Judge and the different setups that can be used to evaluate open-ended problems with an LLM. At the end of the section, we will connect these ideas to rubrics and RL training by overviewing existing RL training techniques and how they are being extended to non-verifiable domains.

LLM-as-a-Judge

Prior to the LLM era, many evaluation metrics used for generative tasks (e.g., BLEU or ROUGE) were quite brittle. These metrics use n-gram matching (or embedding-based matching as in BERTScore) to compare a model’s output to a golden reference answer. Though this approach works relatively well, there are some fundamental problems that arise with reference-based metrics:

We always require a reference answer in order to perform evaluation.

Our output must be similar to this reference answer to perform well.

As we know, LLMs are capable of solving many different tasks, and most of these tasks are open-ended in nature. For example, we can use the same LLM to do creative writing or to answer medical questions. Although these problems are quite different, they do have a fundamental similarity: there are many ways to answer a question correctly. Traditional reference-based metrics struggle to handle such nuanced scenarios where divergence from a chosen reference answer does not imply that an output is bad. As a result, we have seen from several papers that reference-based metrics tend to correlate poorly with human preferences.

“LLM-as-a-judge is a scalable and explainable way to approximate human preferences, which are otherwise very expensive to obtain.” - from [7]

LLM-as-a-Judge is a reference-free metric that prompts a foundation model to perform evaluation based upon specified criteria. Although it has limitations, this technique shows high agreement in many settings with human preferences and is capable of evaluating open-ended tasks in a scalable manner (i.e., minimal implementation changes are required). To evaluate a new task, we simply need to create a new prompt that outlines the evaluation criteria for this task. LLM-as-a-Judge was originally proposed after the release of GPT-4. This metric quickly gained popularity due to its utility and simplicity, culminating in the publication of an in-depth technical report [7]. Today, LLM-as-a-Judge is a widely-used technique in LLM evaluation; e.g., AlpacaEval, Chatbot Arena, Arena-Hard, and more.

Scoring setups. When performing evaluation with an LLM, there are a few different scoring setups that are commonly used (shown above):

Pairwise (preference) scoring: the judge is presented with a prompt and two model responses and asked to identify the better response.

Direct assessment (pointwise) scoring: the judge is given a single response to a prompt and asked to assign a score; e.g., using a 1-5 Likert scale.

Reference-guided scoring: the judge is given a golden reference response in addition to the prompt and candidate response(s) to help with scoring.

This list of scoring setups is not exhaustive, but most scoring setups for LLM-as-a-Judge use some variant or combination of the above techniques. For example, we can derive a pairwise score by scoring two responses independently and comparing their scores. In most cases, we also pair LLM-as-a-Judge with chain-of-thought prompting by asking the model to explain its evaluation process before providing a final score. Not only do such explanations make the evaluation process more interpretable, but they also improve the scoring accuracy of the LLM. Practically, implementing this change can be as simple as adding “Please provide a step-by-step explanation prior to your final score” to your prompt.

“We identify biases and limitations of LLM judges. However, we… show the agreement between LLM judges and humans is high despite these limitations.” - from [7]

Biases of LLM-as-a-Judge. Despite the effectiveness of LLM-as-a-Judge, this technique has several limitations of which we need to be aware. Fundamentally, the LLM judge is an imperfect proxy for human evaluation. By using a model for evaluation, we introduce several sources of bias into the evaluation process:

Position bias: the judge may favor outputs based upon their position within the prompt (e.g., the first response in a pairwise prompt).

Verbosity bias: the judge may assign better scores to outputs based upon their length (i.e., longer responses receive higher scores).

Self-enhancement bias: the judge tends to favor responses that are generated by itself (e.g., GPT-5 can assign higher scores to its own outputs).

Capability bias: the judge struggles with evaluating responses to prompts that it cannot itself solve.

Distribution bias: the judge may be biased towards certain scores in its scoring range (e.g., on a 1-5 Likert scale the judge may output mostly 3’s).

In addition to these biases, LLM judges are generally sensitive to the details of their prompt. Therefore, we should not simply write a prompt and assume proper evaluation. We must calibrate our evaluation process, collect high-quality human labels, and tune our prompt to align well with human judgment; see here.

There are several techniques we can adopt to combat scoring bias; e.g., in-context learning to better calibrate the judge’s score distribution, randomizing position and sampling multiple scores (i.e., position switching), providing high-quality reference answers, or using a jury of multiple LLM judges. For further details on LLM-as-a-Judge, a full overview of the topic is available at the link below.

LLM Evaluation with Rubrics

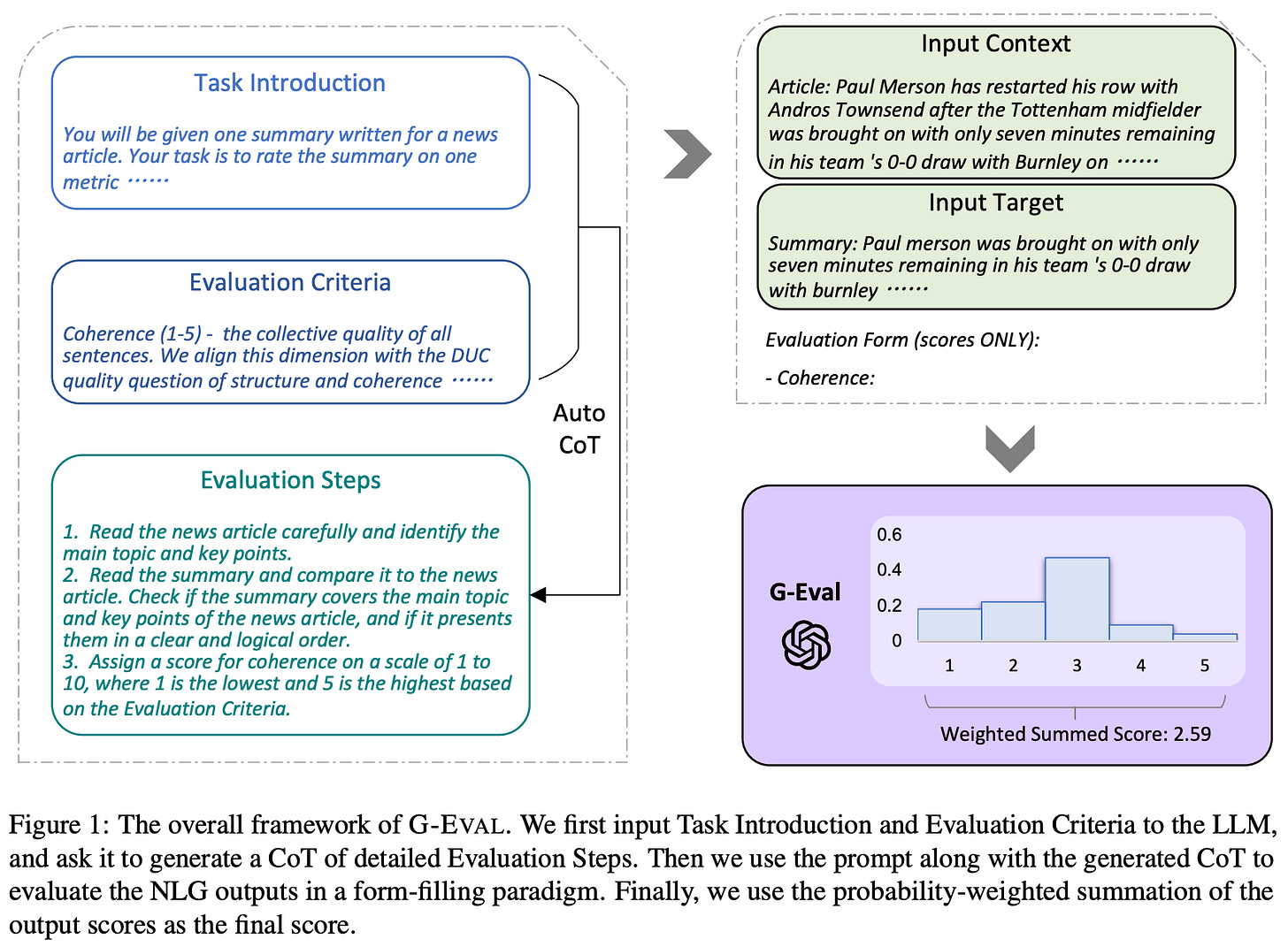

The prompts used for LLM-as-a-Judge in the above section are quite simple. We just describe the evaluation task at a high level and let the LLM judge output a score. However, scoring with a single, general prompt is not always the best approach. Prior work [15] has shown that we can significantly improve the reliability of LLM evaluation by:

Creating several per-criterion scoring prompts.

Providing a step-by-step description of the evaluation process.

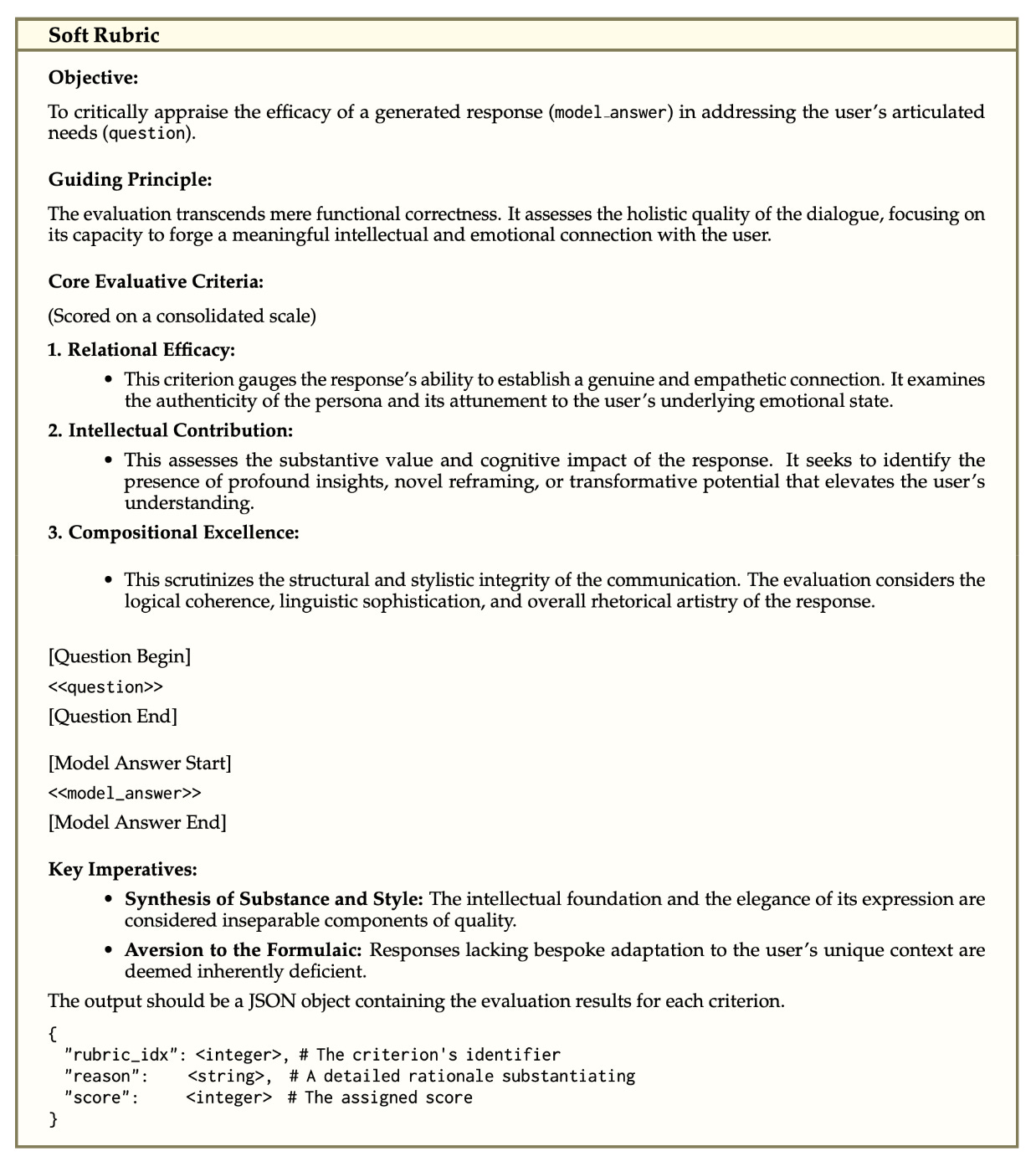

Put simply, providing a granular scoring prompt is beneficial, and we need not stop here. We can create judge prompts targeted to each domain, task, or instance. Increasing the granularity of LLM-as-a-Judge in this way is where the idea of a rubric arises. A rubric is just a scoring prompt that provides a detailed set of criteria by which a response is evaluated; see below. In many cases, rubrics are prompt (or instance)-specific, meaning that a tailored rubric is created for each prompt-response pair being evaluated. These prompt-specific rubrics are often synthetically generated with an LLM—potentially with human intervention.

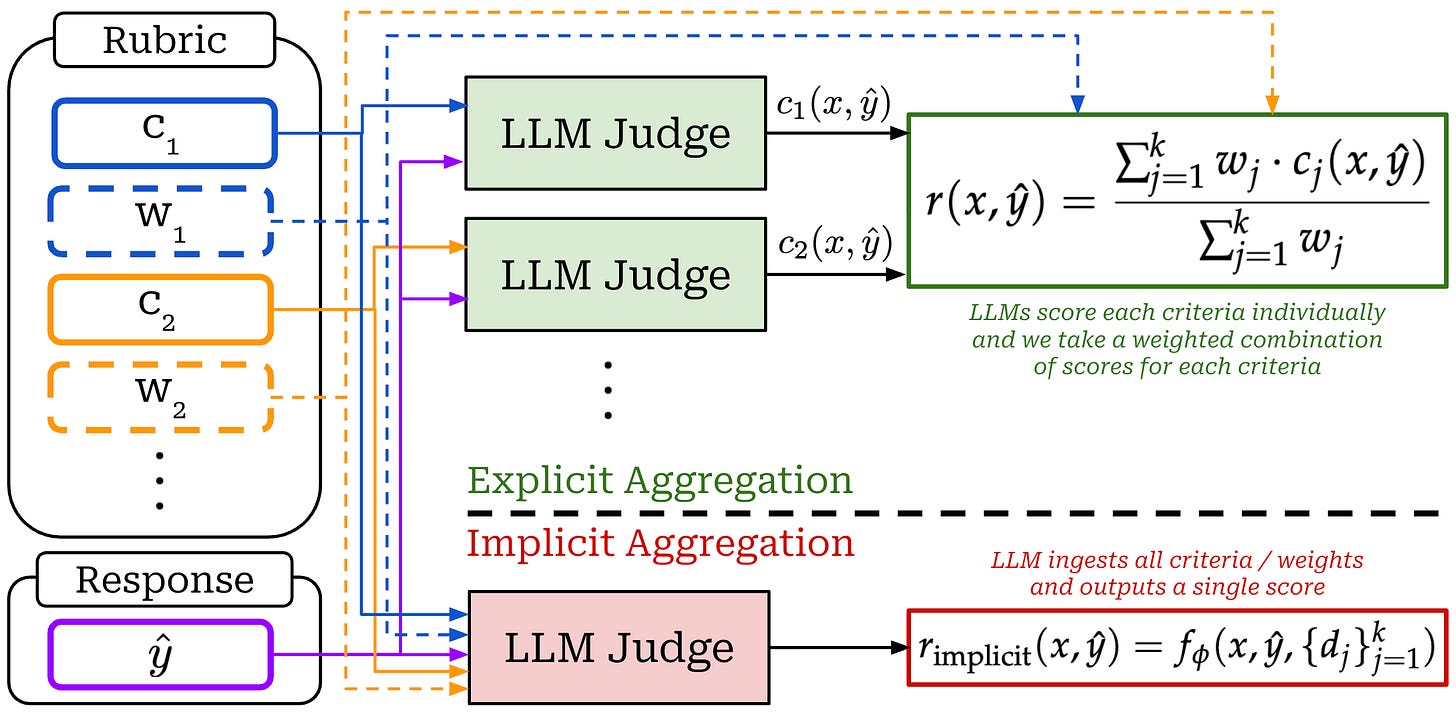

As we can see above, rubrics are usually checklist-style and separated into a list of distinct criteria. Each of these criteria captures a single quality dimension that can be evaluated with an LLM judge. Additionally, in many setups, weights are defined for each criterion to simplify the aggregation of criteria-level scores. Given the similarity of rubrics and vanilla LLM-as-a-Judge, the emergence of rubrics is hard to attribute to a single paper. Rather, the use of rubrics was a slow transition that occurred over time as LLM-as-a-Judge prompts became more granular.

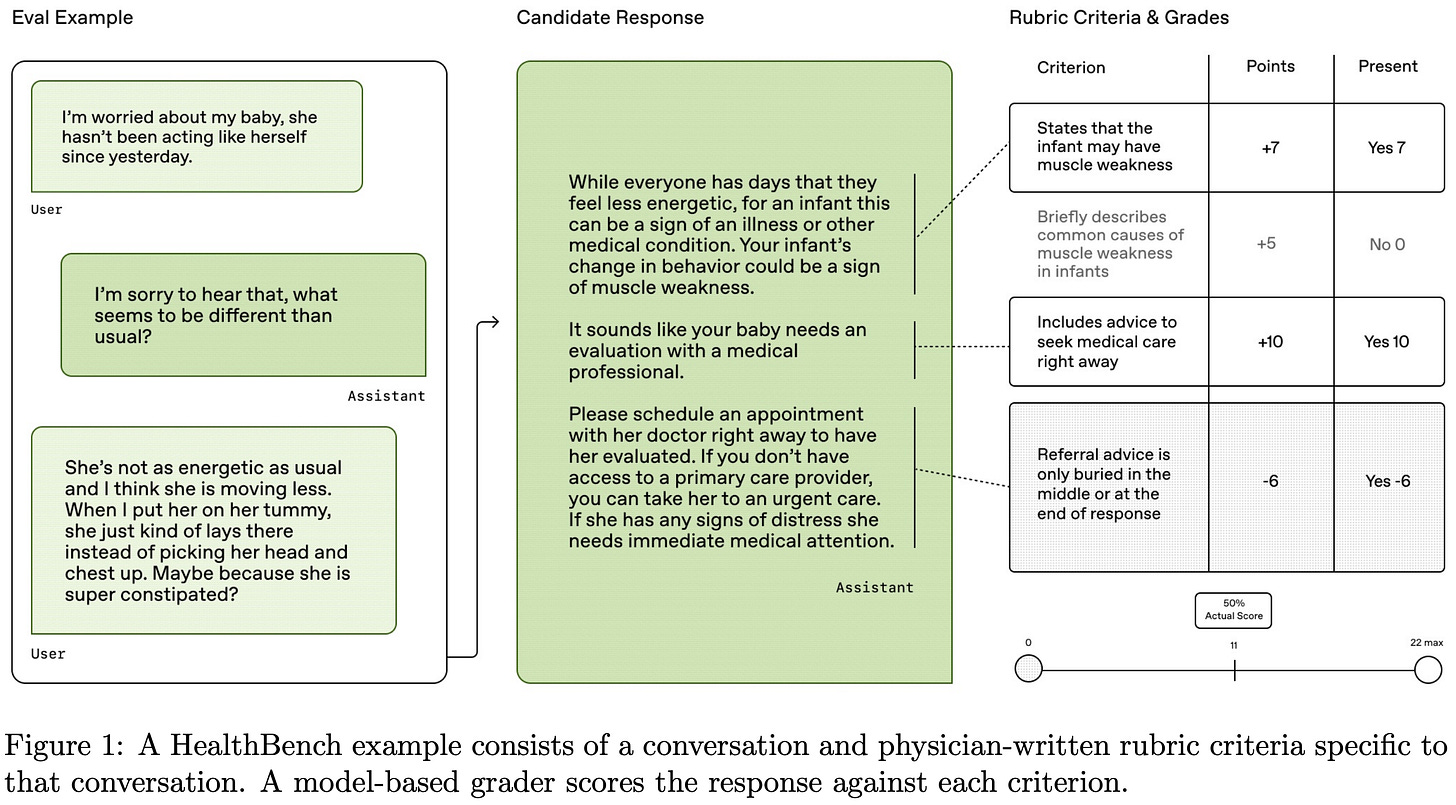

“HealthBench is a rubric evaluation. To grade open-ended model responses, we score them against a conversation-specific physician-written rubric composed of self-contained, objective criteria. Criteria capture attributes that a response should be rewarded or penalized for in the context of that conversation and their relative importance.” - from [16]

In recent work, prompt-specific rubrics have become heavily used for evaluation in expert domains. For example, HealthBench [16] evaluates the quality of medical conversations according to physician-written rubrics that are specific to each conversation; see below. These rubrics focus on detailed and objective criteria—each associated with a weight—that can be verified with an LLM to yield a binary (pass or fail) score. MultiChallenge [17]—a multi-turn chat benchmark focused on tough edge cases like iterative editing, self-coherence, and instruction retention—develops prompt-specific rubrics to improve benchmark reliability, finding that rubrics improve agreement between expert humans and LLM judges.

In this overview, we will go beyond the use of rubrics for evaluation and instead focus on the application of rubrics for deriving a reward signal in RL training. One of the biggest risks when using LLM-as-a-Judge-derived rewards for RL training is reward hacking—LLM judges have known biases that can be exploited. However, we see above that detailed rubrics help to make the evaluation process more reliable, thus reducing risks associated with reward hacking.

RL with Verifiable (and Non-Verifiable) Rewards

Though RL training has long been used for LLMs, the role of RL in LLM training pipelines has become more central with the recent advent of reasoning models. In general, there are two common RL paradigms used for LLMs:

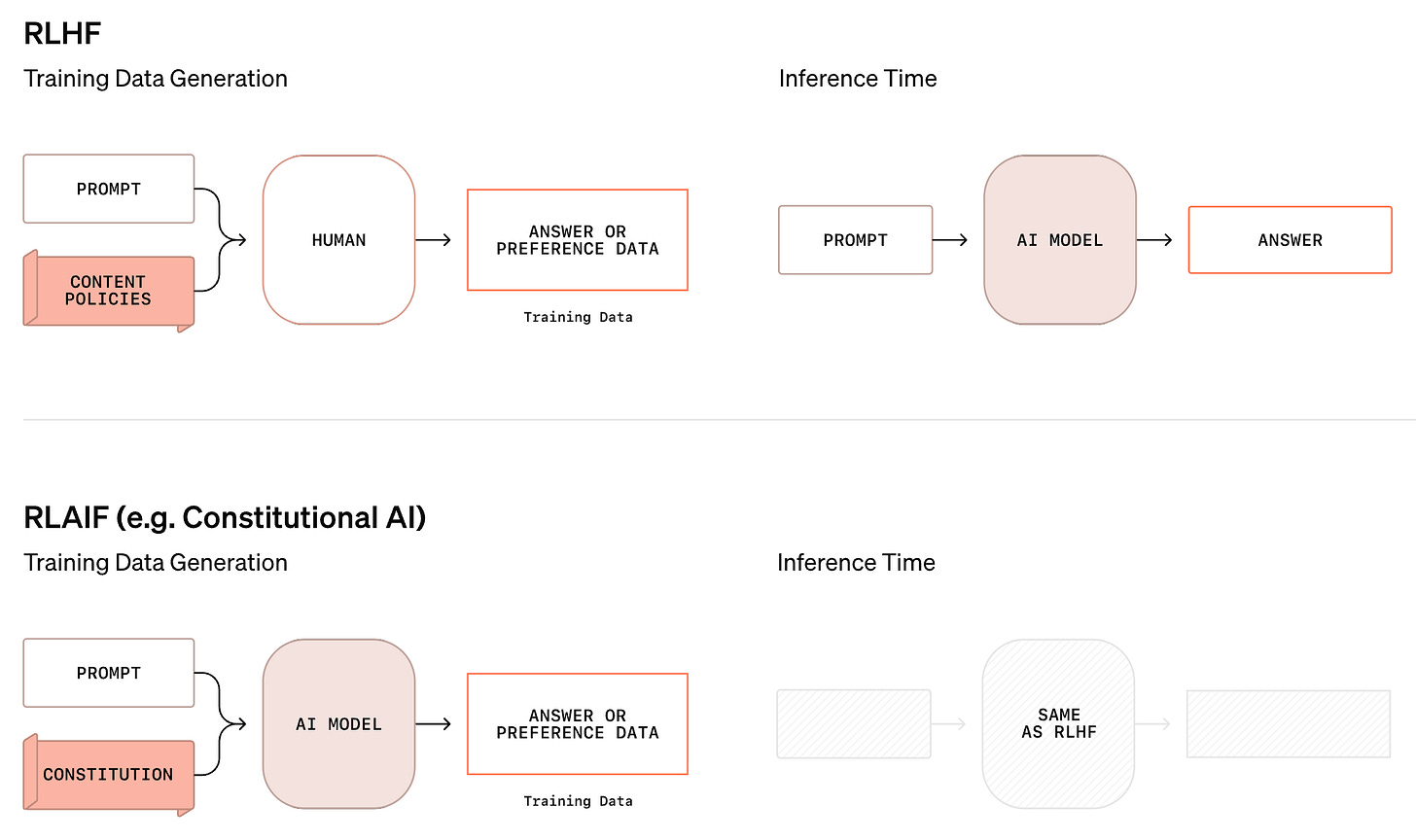

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) trains the LLM using RL with rewards derived from a reward model trained on human preferences.

Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) trains the LLM using RL with rewards derived from rule-based or deterministic verifiers.

The main difference between RLHF and RLVR is how we assign rewards—RLHF uses a reward model, while RLVR uses verifiable rewards. Aside from this difference, both are online RL algorithms with a similar structure; see below. For details on the inner workings of RL optimizers, please see prior posts on PPO and GRPO.

Impact of RLVR. Recent progress in reasoning models has been driven largely by reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR), which derives a reward signal during RL training from deterministic (or programmatic) rules that can be reliably checked (e.g., passing unit tests for code or matching a known numerical answer in math). Using rules-based rewards lowers our risk of reward hacking because we are using a hard rule to derive our reward rather than an LLM-based reward model. As a result, we can run larger-scale RL runs (i.e., over more data and for a larger number of iterations) with less risk of training instability.

On the other hand, the same property that makes RLVR so powerful—the dependence on reliable, rules-based rewards—limits its applicability. Practically, we can only use RLVR on tasks with clean ground-truth labels1 that can be checked automatically. Luckily, several important tasks fall into this category (e.g., math and coding). However, there are many other tasks we would like to solve but are subjective and difficult to verify. Due to this need for verification, we see that LLMs have advanced quickly in certain verifiable capabilities, while gains on non-verifiable tasks have been less uniform. To solve this issue, we need to develop an approach for extending recent advances in RL training to non-verifiable tasks.

“In RLVR, rewards are derived from deterministic, programmatically verifiable signals—such as passing unit tests in code generation or matching the correct numerical answer in mathematical reasoning. While effective, this requirement for unambiguous correctness largely confines RLVR to domains with clear, automatically checkable outcomes.” - from [2]

Open-ended domains. We typically turn to RLHF for training LLMs in open-ended settings. RLHF replaces deterministic verifiers with a learned reward model trained on preference data; see below. Preference data can be collected for any domain by simply sampling multiple completions for each prompt and having a human (or model) select the better of the two. We can drastically increase domain coverage by using RLHF. However, relying upon preference data and reward models introduces notable difficulties and failure modes:

A large volume of preference data must be collected.

We lose granular control over the alignment criteria—preferences are expressed in aggregate over a large volume of data rather than via explicit criteria.

The reward model can overfit to artifacts (e.g., response length, formatting, etc.) and generally introduces more risk of reward hacking.

RLHF is a general technique, but it is usually used in practice for improving broad, subjective properties; e.g., helpfulness, harmlessness, or style. For complex, open-ended tasks, the reward signal tends to be multi-dimensional. Traditional reward modeling captures these quality dimensions via a single preference label, which eliminates our ability to specify quality dimensions at a more granular level. One could collect criterion-level preferences to solve this issue, but doing so requires training (and maintaining) separate reward models per criterion and increases the volume of data that must be collected. A natural alternative is to make evaluation dimensions explicit by using a rubric to ground the reward in structured, interpretable criteria rather than a single judgment.

Rubrics-as-Rewards. The idea of deriving a reward from a rubric-based LLM judge is one of the current frontiers of RL research—it presents an opportunity to extend RLVR to arbitrary open-ended tasks. Although this area of research is still nascent and evolving quickly, the idea of using rubrics for RL is not new! Similar ideas have already been proposed for better handling the safety alignment of LLMs. During LLM alignment, we have a detailed list of safety specifications that describe the desired behavior of the model. These specifications are changed frequently as new needs or failure cases arise in practice. The dynamic nature of safety criteria makes applying a standard RLHF approach difficult—the preference data must be adjusted or re-collected each time that our criteria change.

To avoid the need for constant data collection, methods like Constitutional AI [13] and Deliberative Alignment [14] show that a reliable reward signal can be derived directly from the safety specifications themselves. More specifically, we can provide safety criteria as input to a strong reasoning model that is used to generate data or evaluate model outputs according to these criteria. Due to the strong instruction following capabilities of frontier-level reasoning models, this approach is capable of providing a reliable reward signal for safety training.

“Collecting and maintaining human data for model safety is often costly and time-consuming, and the data can become outdated as safety guidelines evolve with model capability improvements or changes in user behaviors. Even when requirements are relatively stable, they can still be hard to convey to annotators. This is especially the case for safety, where desired model responses are complex, requiring nuance on whether and how to respond to requests.” - from [9]

This approach avoids the need to re-collect data as criteria change. Rather, we just maintain a clear, itemized list of safety criteria—basically a safety rubric—that can be provided as input to the alignment system. Instead of collecting data, we focus on creating a “constitution” that dictates the behavior of our model. Once this constitution is available, we rely upon an LLM judge to apply the necessary supervision for achieving this desired behavior. This approach is both dynamic and interpretable, but it can only be applied in domains where the LLM judge is known to perform well. Extending similar techniques to arbitrary domains, which we will explore for the remainder of this post, is a non-trivial research problem.

Using Rubrics for RL

We now have a detailed understanding of LLM-as-a-Judge, rubrics, and their application to RL training. Next, we will extend these ideas by overviewing a broad collection of recent papers that study the application of rubrics to RL training. Many papers have been written on this topic in quick succession. As we will see, however, much of this work shares a similar flavor. Slowly, rubric-based RL has become more effective across a wider variety of tasks, enabling powerful reasoning models to achieve impressive gains even in non-verifiable domains.

Rubrics as Rewards: Reinforcement Learning Beyond Verifiable Domains [1]

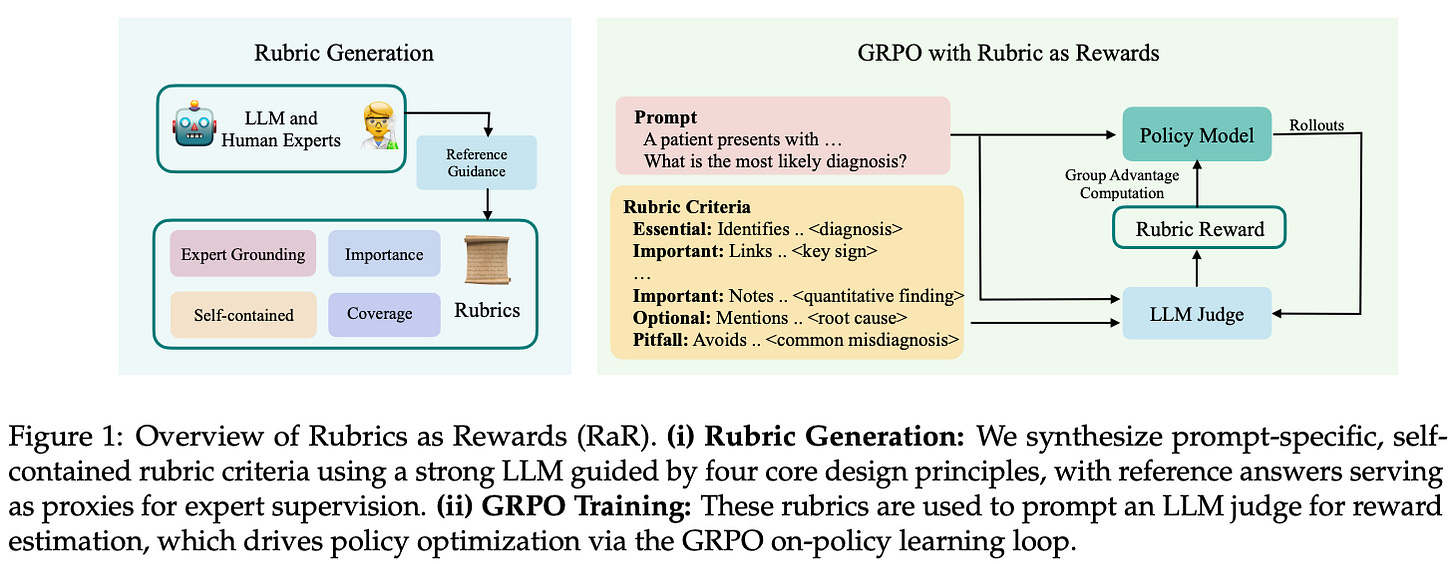

“Rather than using rubrics only for evaluation, we treat them as checklist-style supervision that produces reward signals for on-policy RL. Each rubric is composed of modular, interpretable subgoals that provide automated feedback aligned with expert intent. By decomposing what makes a good response into tangible, human-interpretable criteria, rubrics offer a middle ground between binary correctness signals and coarse preference rankings.” - from [1]

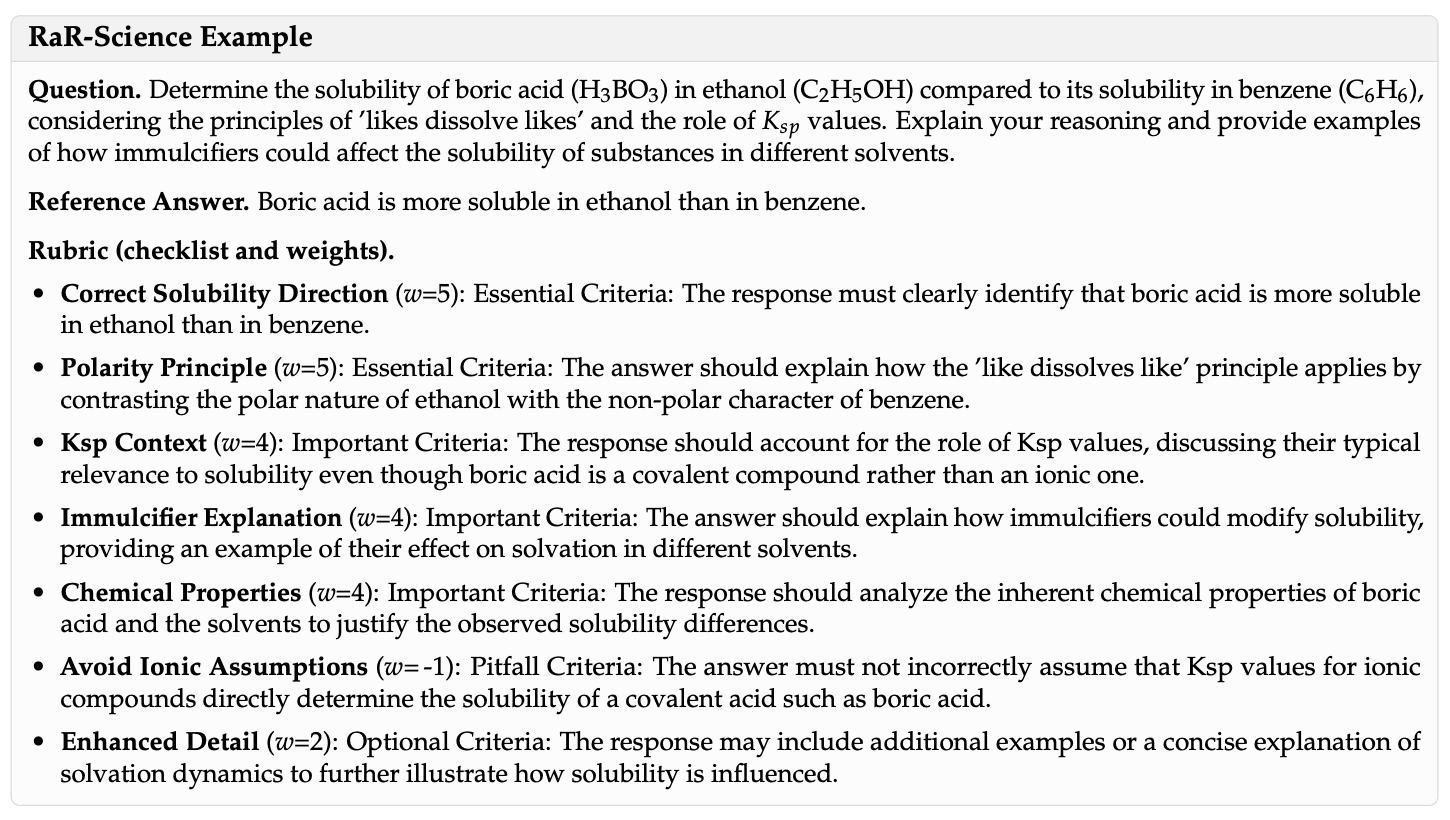

RLVR is effective in verifiable domains with a clear correctness signal like math or coding, but there are many domains in the real world that are not strictly verifiable (e.g., science or health). For these domains, we need a more versatile reward mechanism—such as an LLM judge or reward model—that can handle open-ended problems that lack a clear or verifiable answer. Going beyond a vanilla LLM-as-a-Judge setup, we see in [1] that prompting the LLM judge with a rubric composed of structured, instance-specific—meaning unique to each prompt—criteria benefits the model’s performance in on-policy RL training.

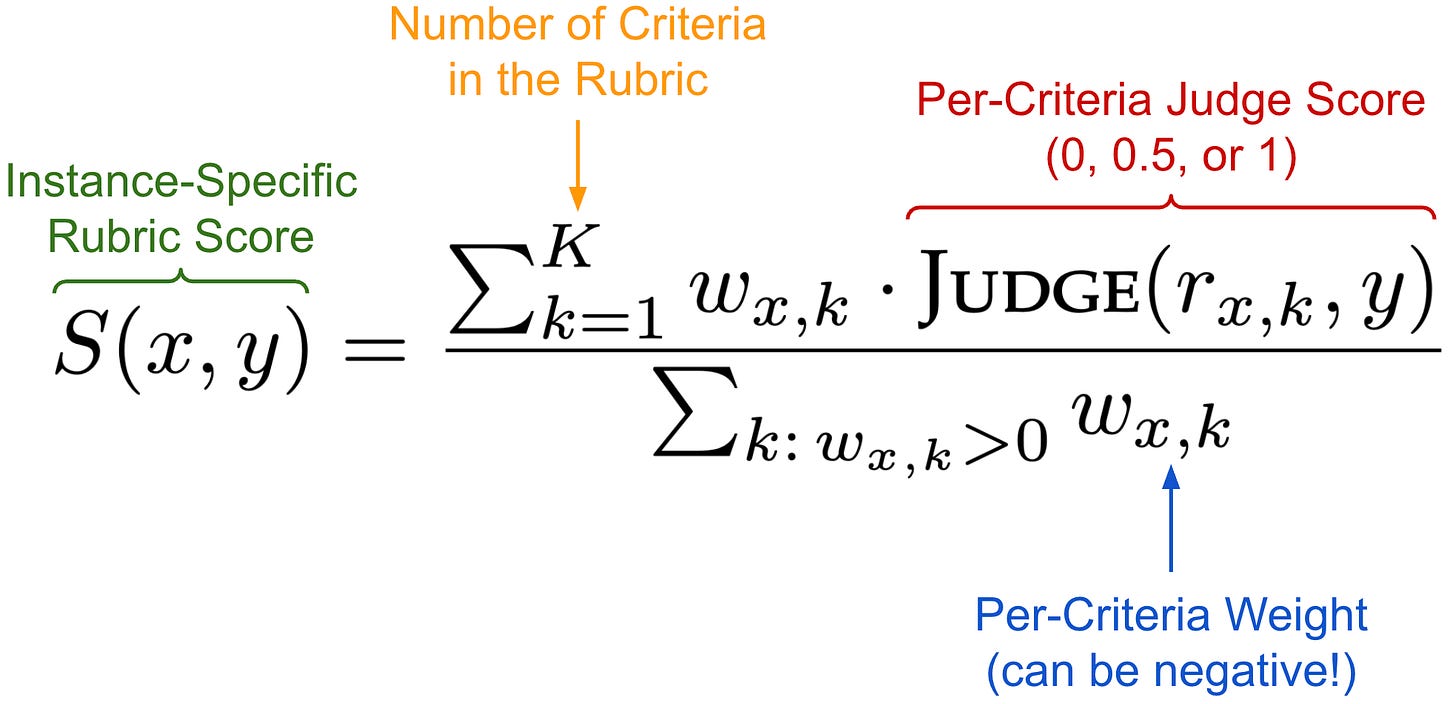

Creating rubrics. Rubrics in [1] are checklist-style and cover multiple criteria that are specific to each prompt being scored. The checklist for a rubric contains K total criteria c_i, each with a corresponding weight w_i. A criterion is defined as a binary correctness check that can be validated using an LLM judge. We can also recover an RLVR setup by assuming K = 1 and letting c_1 be a deterministically verifiable reward signal with weight w_1 = 1.0.

We refer to this approach of using rubrics to generate a reward signal for RL as Rubrics-as-Rewards (RaR). There are two approaches we can use to evaluate a rubric and derive a reward for RL training (shown above):

Explicit aggregation: each criterion is independently evaluated using an LLM judge, and the final reward is derived by summing and normalizing the weighted score of each criterion.

Implicit aggregation: all criteria along with their weights are passed to an LLM judge, which is asked to derive a final reward that considers all information.

Explicit aggregation provides more granular control over the weight of each criterion, which can aid in interpretability but requires tuning and can be fragile. In contrast, the implicit aggregation approach delegates the reward aggregation process—including handling the weights of each criterion—to the LLM judge.

Generating rubrics. All instance-specific rubrics used in [1] are generated by an LLM; see above. When generating rubrics, guiding principles are provided to the model with respect to how rubrics should be created. Namely, rubrics must i) be grounded in guidance from human experts, ii) be comprehensive (i.e., span many dimensions of quality), iii) specify per-criterion importance (e.g., factuality is more important than style), and iv) use self-contained criteria (i.e., criteria should not depend on one another). Given these desiderata and a golden (expert-curated) reference answer for a prompt, the LLM then generates a rubric that includes:

7-20 self-contained criteria.

A numeric or categorical (i.e., essential, pitfall, important, or optional2) weight for each of these criteria.

Numeric weights provide fine-grained control over criterion importance, but categorical weights, each of which are mapped to a numerical score, are more interpretable—both for humans and the LLM—which leads them to be used for experiments in [1]. Once generated, a rubric can be used as a reward function by passing it to an LLM judge and performing explicit or implicit aggregation.

“We generate rubrics using OpenAI’s o3-mini and GPT-4o, conditioning generation on reference answers from the underlying datasets to approximate expert grounding. The resulting collections—RaR-Medicine and RaR-Science—are released for public use.” - from [1]

Experimental settings. In [1], authors see rubrics as an opportunity to provide flexible, scalable, and interpretable reward signals for RL in real-world domains that go beyond verifiable problems like code and math. Moving in this direction, two non-verifiable domains are considered in [1]: medicine and science. Prompts and rubrics used for RL in [1] are sampled from a mixture of public datasets, such as NaturalReasoning, SCP-116K, and GeneralThought-430K. This data is further curated to create two datasets for RaR training in [1]:

RaR-Medicine: ~20K prompts focused on medical reasoning with instance-specific rubrics generated with GPT-4o.

RaR-Science: ~20K prompts curated to align with the problem categories from GPQA-Diamond with instance-specific rubrics generated by o3-mini.

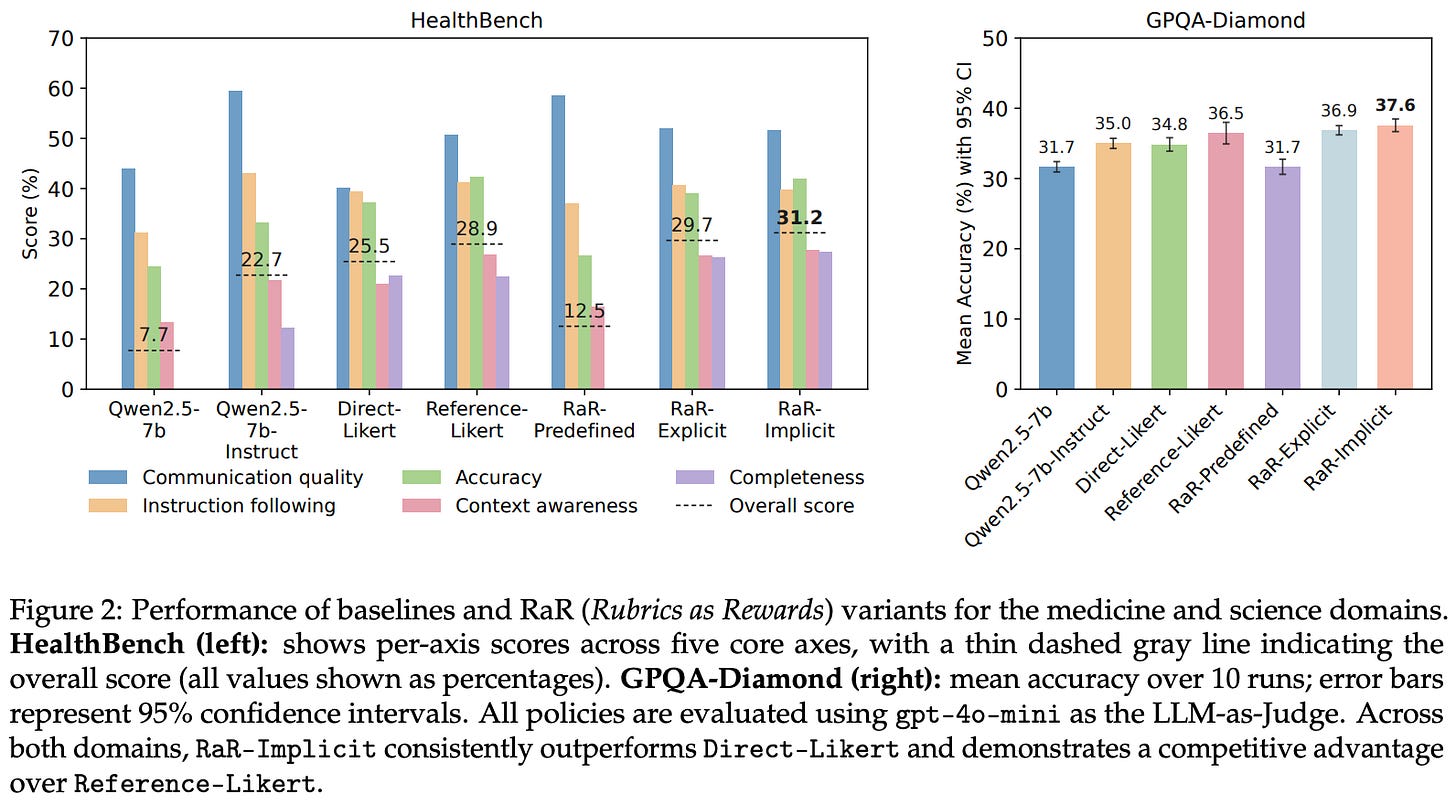

All experiments use Qwen-2.5-7B as a base model and train with GRPO. Rewards are assigned using GPT-4o-mini with the instance-level rubrics described above. The proposed technique in [1], referred to as RaR-Implicit, uses LLM-generated, instance-specific rubrics with implicit aggregation as a reward signal. Several rubric-free and fixed-rubric baselines are also considered:

Base models: Qwen-2.5-7B and Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct models are evaluated with no additional training.

Direct Assessment Judge: an LLM judge provides a direct assessment score for each response on a 10-point Likert scale—this is a standard LLM-as-a-Judge setup that does not use a granular, instance-specific rubric.

Reference-Based Judge: same as above, but the LLM judge is given a golden reference answer as context when generating a score.

RaR-Predefined: a fixed set of generic rubrics are used for all prompts with explicit aggregation and uniform criteria weights.

RaR-Explicit: instance-specific rubrics are used, but all criteria receive fixed weights based on their categorical importance label.

All models are evaluated on the GPQA-Diamond (Science) and HealthBench (medicine) benchmarks. For some smaller ablation experiments, RL training is performed on the training set of HealthBench rather than RaR-Medicine.

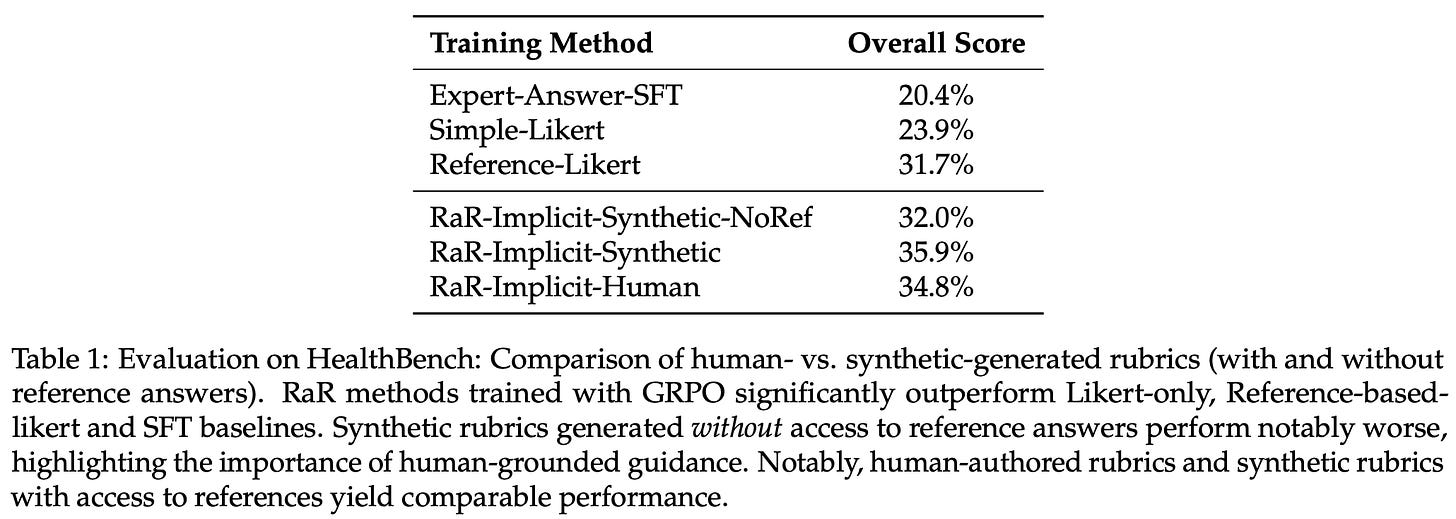

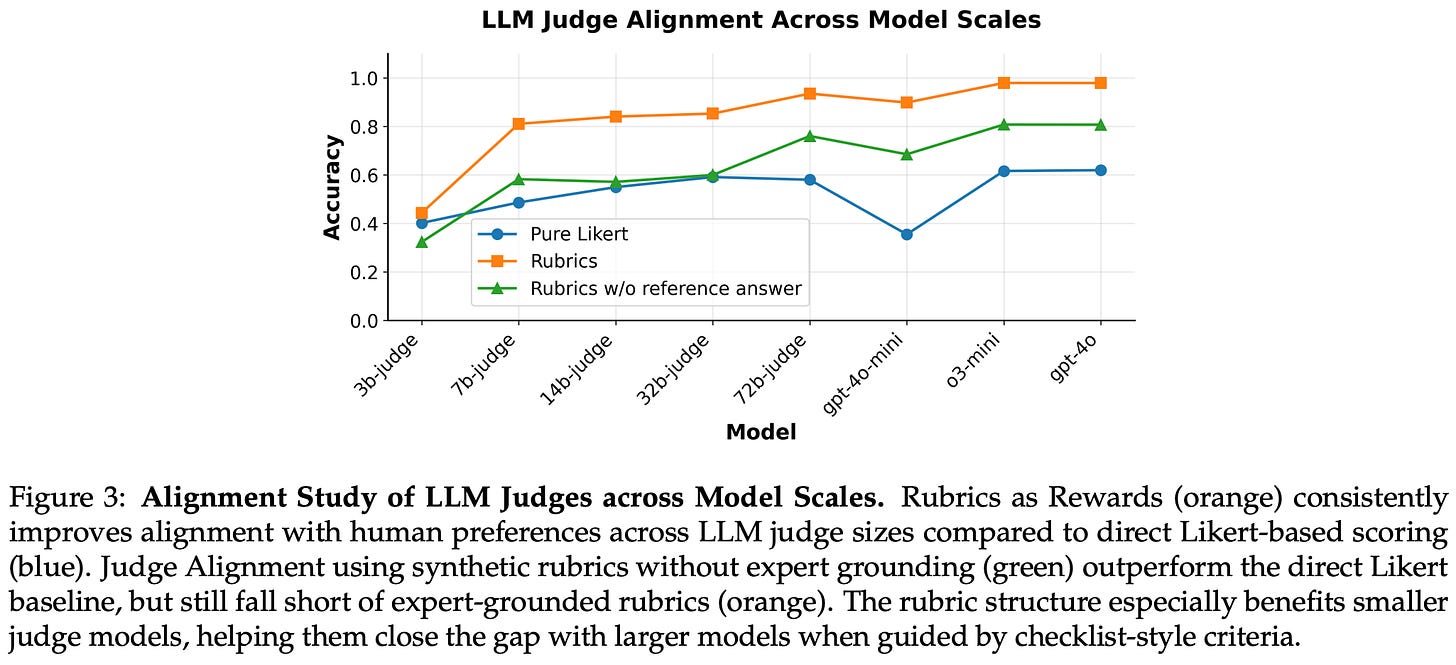

Do rubrics provide useful rewards? Across all experiments in [1], we see that using structured, rubric-based rewards during RL training is beneficial. Rubric-based rewards are especially impactful when using smaller LLM judges for RL training and are found to reduce variance in reward signals across different sizes of LLM judges. As shown above, rubric-based approaches outperform all rubric-free methods aside from the reference-based LLM judge, relative to which we only see marginal gains from rubrics. However, rubrics are found to yield a more notable gain over reference-based LLM judge rewards in later experiments that train on HealthBench; see below. We also see that implicit aggregation tends to outperform explicit aggregation by a small (but consistent) margin.

“Rubric-guided training achieves strong performance across domains, significantly outperforming Likert-based baselines and matching or exceeding the performance of reference-based reward generation.” - from [1]

These experiments also highlight the necessity of expert-curated references for generating rubrics—performance noticeably deteriorates without references, indicating purely synthetic rubrics are suboptimal. Predefined or generic rubrics are also found to perform quite poorly, indicating that prompt-specific criteria are useful for deriving high-quality rubrics. These best practices for creating better rubrics are also evaluated beyond their impact on RL training. In [1], authors show that rubrics created via their proposed approach have noticeably higher levels of agreement with preference annotations from human experts; see below.

Reinforcement Learning with Rubric Anchors [2]

“The success / failure hinges tightly on the diversity, granularity, and quantity of the rubrics themselves, as well as on a proper training routine and meticulous data curation.” - from [1]

Authors in [2] continue studying the application of RL to open-ended tasks using rubric-based rewards. They scale the rubric creation process to produce a dataset of ~10K rubrics curated by humans, LLMs, or a combination of both. Building on this dataset, a practical exposition of rubric-based RL is provided, ultimately arriving at a functional RaR training framework called Rubicon. Interestingly, simply increasing the number of rubrics—whether generated synthetically or with human assistance—yields only marginal gains. Instead, we must carefully curate high-quality rubrics, suggesting that the success of RaR heavily depends upon both rubric quality and the quality of the underlying training dataset.

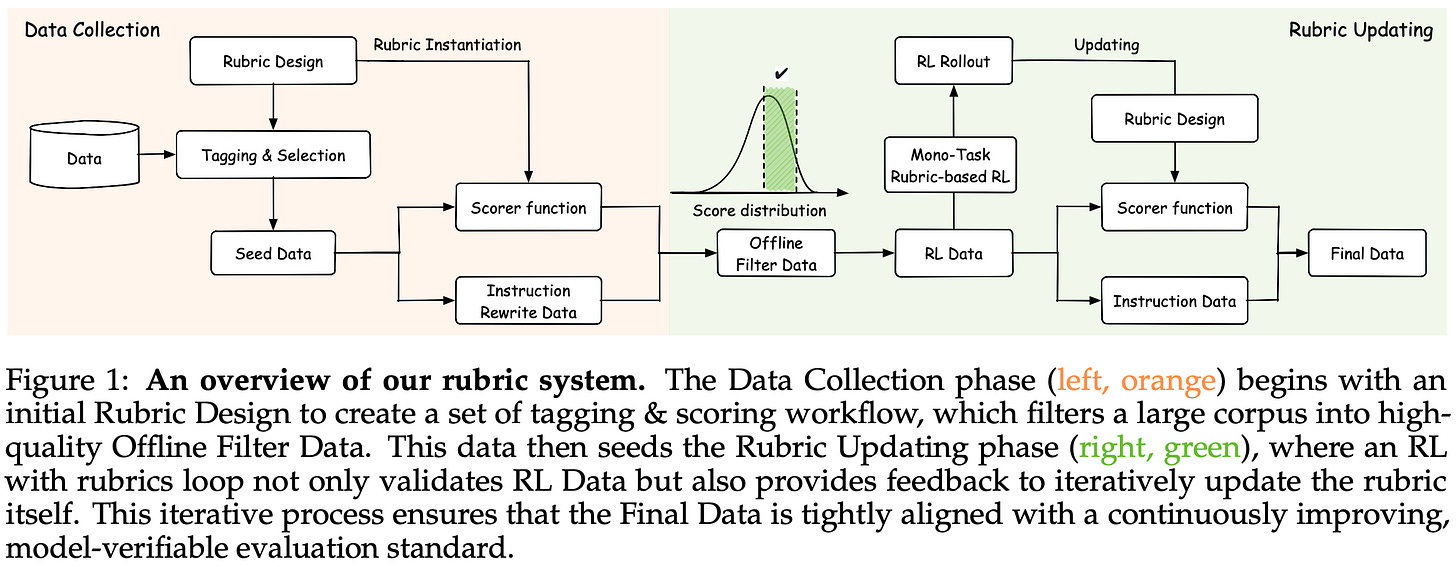

Rubric system. Instead of using strictly instance-level rubrics, multiple scopes are considered in [2], including instance, task, and dataset-level rubrics. When generating data, the system in [2] (shown below) starts by constructing the rubric first. Data is synthesized only after the rubric is created so that it explicitly matches the rubric. Then, the combination of rubric and data is used for both RL training and evaluation. Tasks in [2] are selected according to the asymmetry of verification—verifying a candidate output should be much easier than generating it.

To ensure rubric quality, authors run dedicated ablation experiments for every set of rubrics that is generated to measure their impact on the training process. Each rubric is comprised of K criteria C = {c_1, c_2, …, c_K}. An example of a rubric created for evaluating open-ended or creative tasks is provided below. After evaluating each of these criteria, we are left with a multi-dimensional reward vector that can be aggregated to yield a final reward.

As a baseline, criteria-level rewards can be aggregated via a weighted average, but non-linear dependencies may exist between criteria that make a weighted average suboptimal. For this reason, authors in [2] consider the following advanced strategies for criteria aggregation:

Veto Mechanisms: failing on a critical dimension overrides any reward from other dimensions.

Saturation-Aware Aggregation: over-performing on a single dimension yields diminishing returns relative to a balanced reward across dimensions.

Pairwise Interaction Modeling: criteria are modeled together to capture inter-criteria relationships (i.e., synergistic or antagonistic effects).

Targeted Reward Shaping: rewards in high-performance regions are amplified to better capture differentials and avoid scores becoming compressed.

Training strategy. The data used in [2] is derived from a proprietary post-training corpus with ~900K examples. Prior to any training, offline difficulty filtering is performed to remove any examples on which the base model performs too poorly or already performs well3. From here, RL training progresses in two phases, each with a different curriculum:

The first phase focuses on instruction-following and programmatically-verifiable tasks to teach the LLM how to properly handle constraints.

The second phase extends the training process to more open-ended and creative tasks with a higher level of subjectivity.

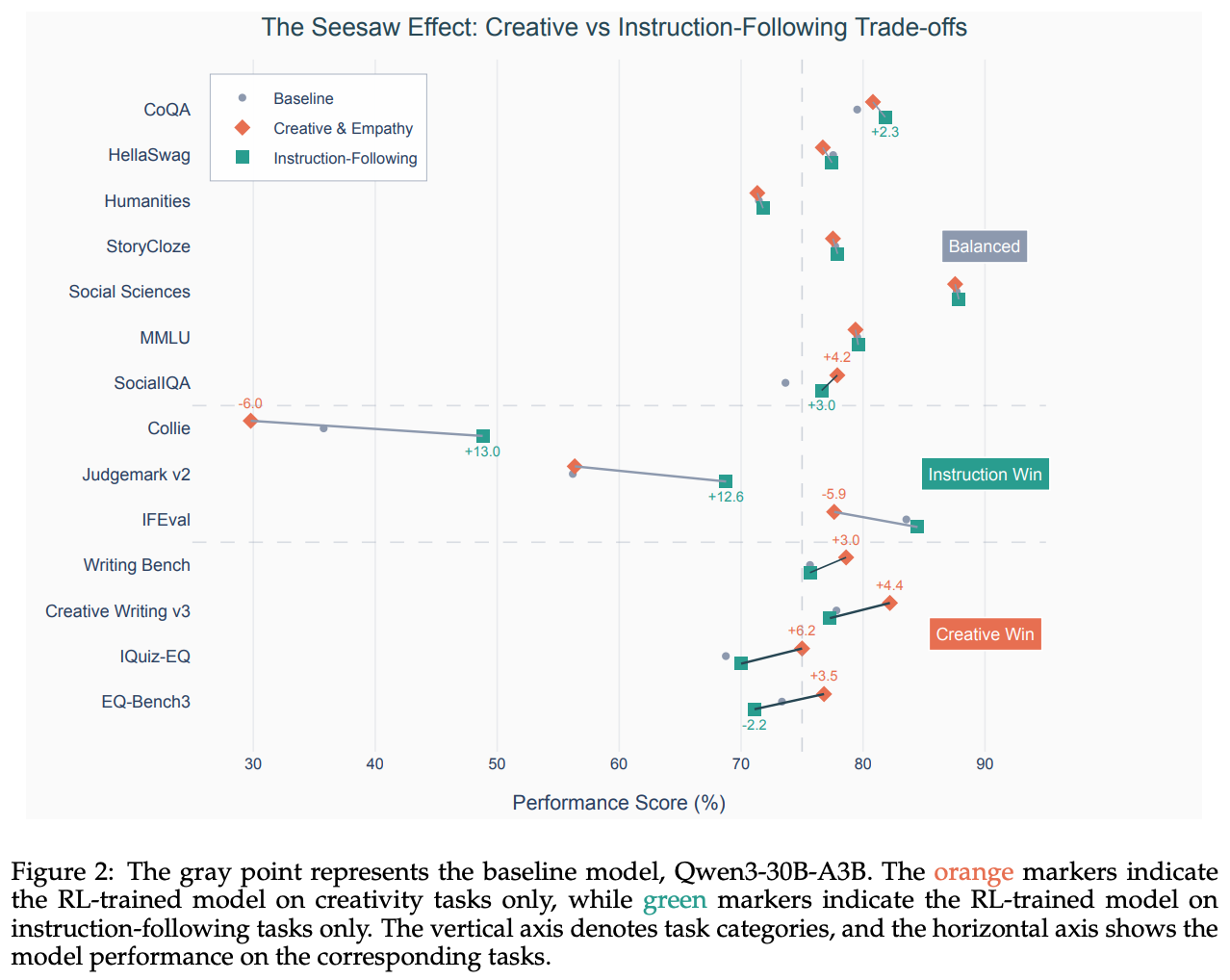

While the first phase primarily relies upon static rubrics and verifiers, we must use reference-based rubrics—often with instance-specific criteria—for the second phase. Granular rubrics help to provide a more reliable reward signal on tasks that are highly subjective. This multi-stage training framework aims to progressively cultivate the capabilities of the model. When training jointly on all tasks, authors observe a “seesaw effect”—joint training actually reduces model performance relative to forming a multi-stage curriculum; see below.

Reward hacking is one of the biggest risks in a RaR setup. Whereas verifiable rewards are deterministic, neural reward models can be exploited, and the likelihood of our policy finding such an exploit increases in large-scale RL runs4. The Rubicon approach proposed in [2] combats reward hacking by performing an offline analysis of rollout data. After the first phase of RL training, authors examine rollouts that yield abnormally high rewards and create a basic taxonomy of recurring reward hacking patterns that are discovered. From this taxonomy, a specific rubric is created for preventing reward hacking—this rubric can also be iteratively refined over time. The addition of a reward hacking rubric improves training stability (i.e., avoids collapse into a reward-hacked state) and allows RL training to be conducted for a much larger number of training steps.

“Applying RL with rubrics from different task types could create conflicting objectives, leading to performance trade-offs — a phenomenon we refer to as the seesaw effect… training exclusively with instruction-following rubrics improves compliance but reduces creativity, while training exclusively with creativity and empathy rubrics enhances open-ended responses but harms strict adherence… These results suggest that simply combining all rubric types in a single RL run is likely to intensify such conflicts. To overcome this, we adopt a multi-stage RL strategy.” - from [2]

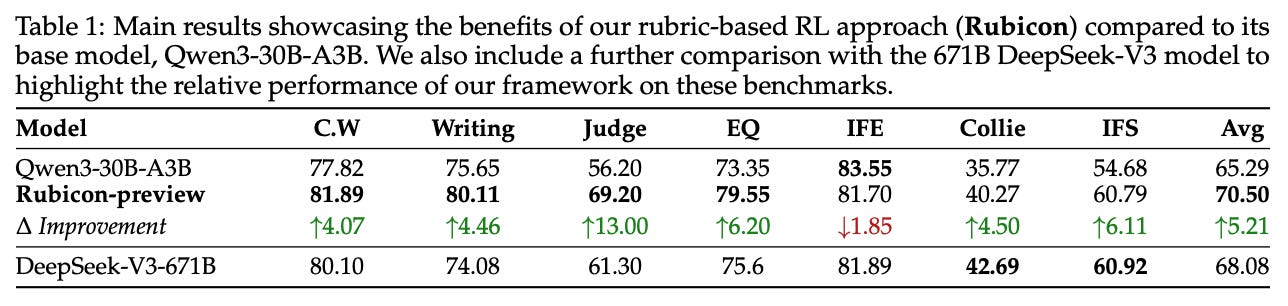

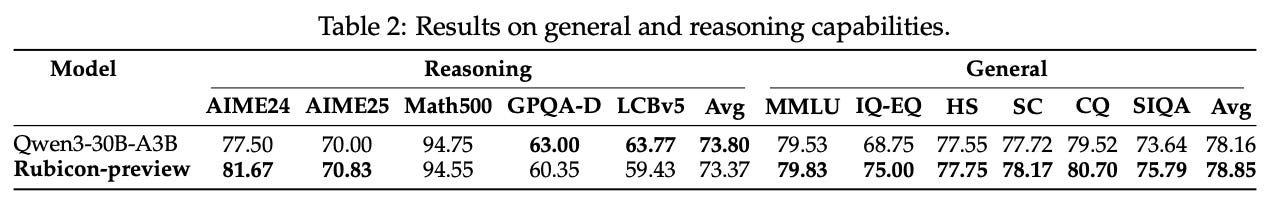

Rubicon-preview is a Qwen-3-30B-A3B base model that is finetuned in [2] using the Rubicon framework. This model excels in open-ended and humanities-related benchmarks. For example, we see below that Rubicon-preview achieves an absolute improvement of 5.2% compared to the base model on various instruction following, emotional intelligence, and writing benchmarks. Notably, Rubicon-preview also outperforms DeepSeek-V3-671B on most of these tasks, where an especially significant performance boost is observed on writing tasks.

The performance benefits of Rubicon-preview are also achieved with shocking sample efficiency—the model is only trained on ~5K data samples. By using an RaR approach, authors are also able to granularly control the style or voice of the resulting model. More specifically, a few case studies are presented in [2] that demonstrate the use of rubrics to guide the LLM away from the didactic tone that is common of chatbots and towards a human-like tone with more emotion.

Going further, creatively-oriented RaR training does not seem to damage the LLM’s general capabilities. As shown above, Rubicon-preview performs on par with or better than the original base model across a wide scope of benchmarks. Such a result should not come as a surprise given the natural ability of RL to avoid forgetting and retain the prior knowledge or skills of an LLM; see here.

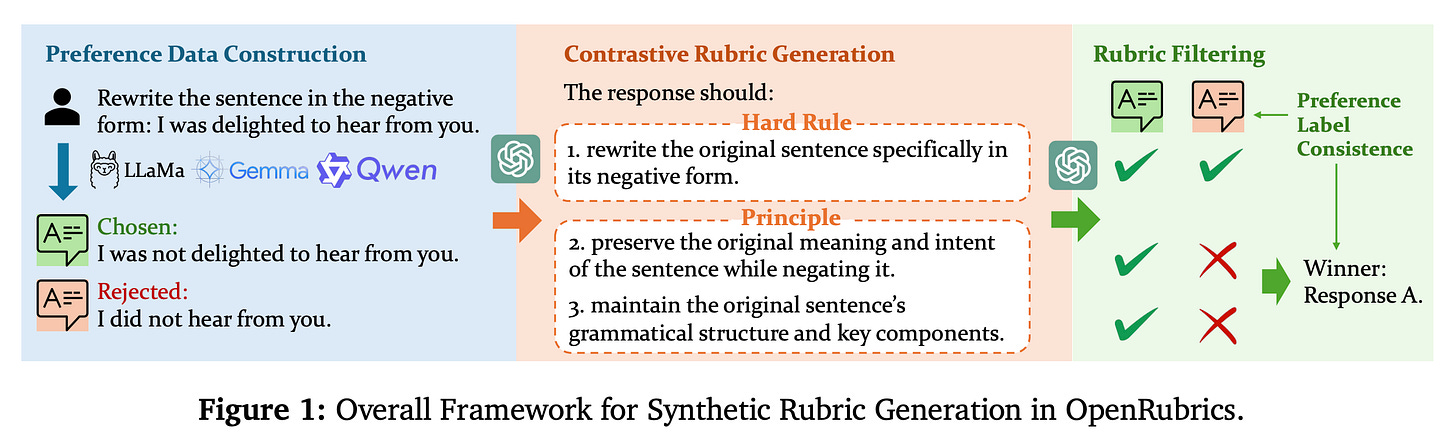

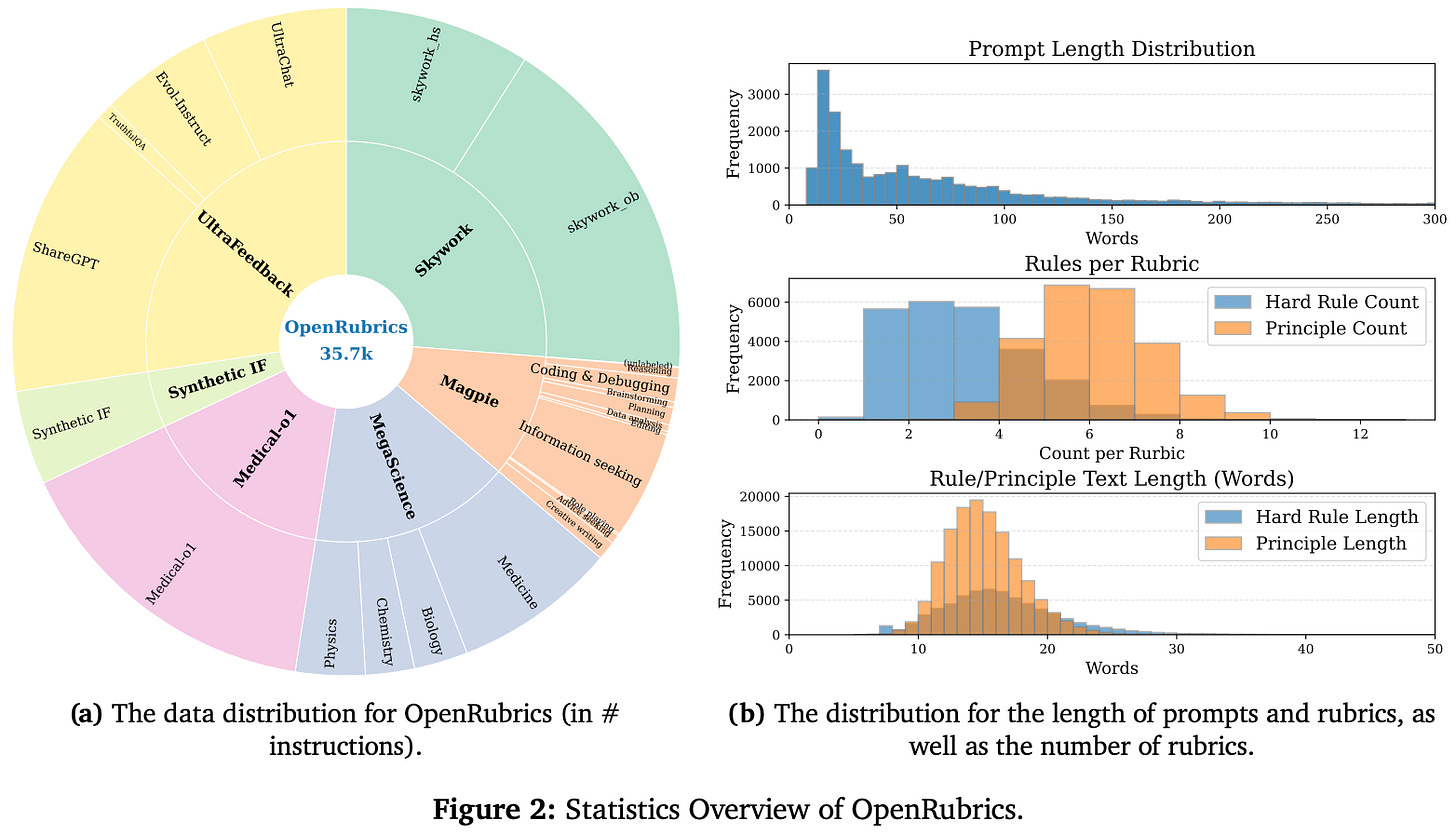

OpenRubrics: Towards Scalable Synthetic Rubric Generation for Reward Modeling and LLM Alignment [3]

We’ve seen several papers that study the use of rubrics for RL training, where rubrics are generated—possibly with human intervention—and evaluated by an off-the-shelf LLM. Instead of focusing upon the downstream application of rubrics in RL, authors in [3] specifically analyze the rubric generation and evaluation process. To facilitate this study, an open dataset of prompt-rubric pairs, called OpenRubrics, is created for training both rubric generation models and rubric-based reward models. As we learned in [2], RaR training is highly dependent upon rubric quality. Creating better rubrics—and reducing the amount of human supervision in this process—makes RaR training more scalable and effective.

The rubric structure used in [3] is consistent with prior work. Namely, each rubric is comprised of K criteria, where each criterion is a rubric description that specifies one aspect of response quality. Two types of criteria are considered:

Hard rules: explicit or objective constraints (e.g., length or correctness).

Principles: higher-level qualitative aspects (e.g., reasoning soundness, factuality, or stylistic coherence).

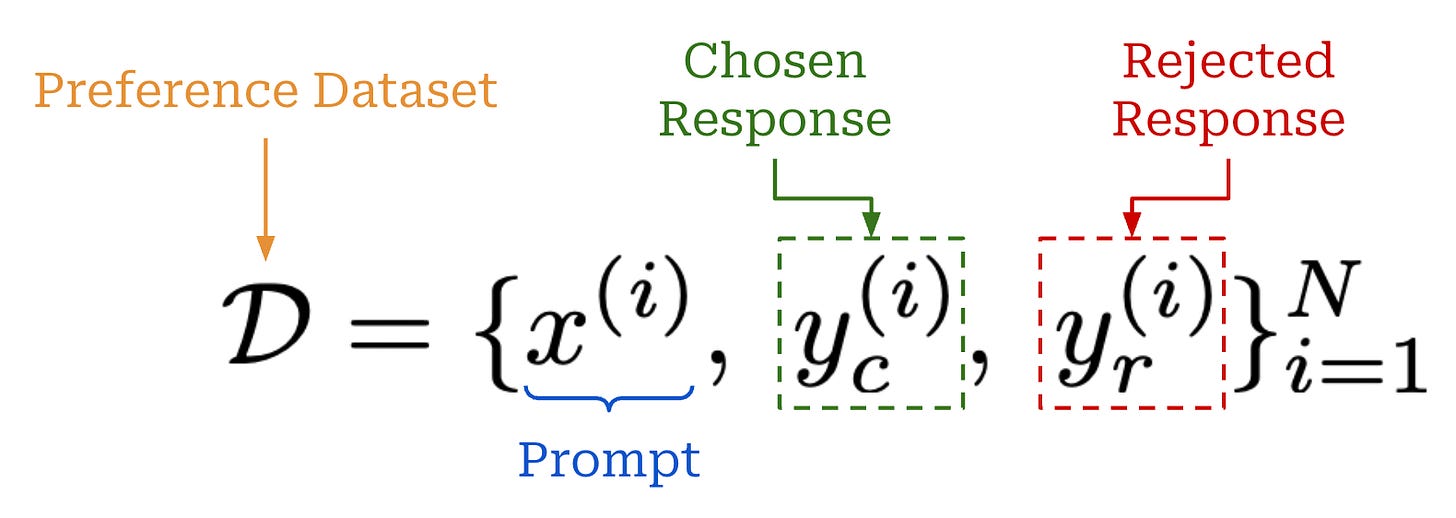

Unlike prior work, rubrics in [3] do not use per-criterion weights and are used for pairwise comparison of two completions—as opposed to direct assessment. For a rubric R = {c_1, …, c_K} and two responses y_1 and y_2 to the same prompt x, we want our rubric-based reward model to provide a binary preference label (i.e., y_1 > y_2 or y_1 < y_2) by reasoning over the rubric criteria.

“We prompt the LLM to generate two complementary types of rubrics: hard rules, which capture explicit and objective constraints specified in the prompt, and principles, which summarize implicit and generalizable qualities of strong responses. This design allows the rubrics to capture both surface-level requirements and deeper dimensions of quality. Although hard rules are typically straightforward to extract, the principles are more subtle and require fine-grained reasoning.” - from [3]

Building OpenRubrics. The prompts and preference labels used for creating OpenRubrics are sourced from several public datasets (e.g., UltraFeedback, MegaScience, Medical-o1, instruction following data from Tulu-3, and more). For each of these datasets, preference data is obtained via domain-specific post-processing of the existing data. For example, the highest and lowest scoring responses form a preference pair for UltraFeedback, while for MegaScience and Medical-o1 completions are generated with a pool of LLMs and scored via a jury of different reward models to obtain preference pairs; see below.

Once this preference data is available, rubrics are generated using two key strategies proposed in [3] (shown above):

Contrastive Rubric Generation (CRG): an instruction-tuned LLM is provided both a prompt and a preference pair and asked to produce discriminative evaluation criteria by contrasting the chosen and rejected responses.

Rubric Filtering: rubrics are filtered by prompting an LLM to choose the preferred response given a preference pair and rubric as input and only retaining rubrics that yield agreement with human-provided preference labels (i.e., preference label consistency)5.

CRG and rubric filtering aim to create rubrics that are both prompt-specific and aligned with human preference examples, allowing them to serve as useful anchors for reward modeling. The result of this rubric generation and filtering approach is OpenRubrics, the key statistics of which are summarized in the plots below.

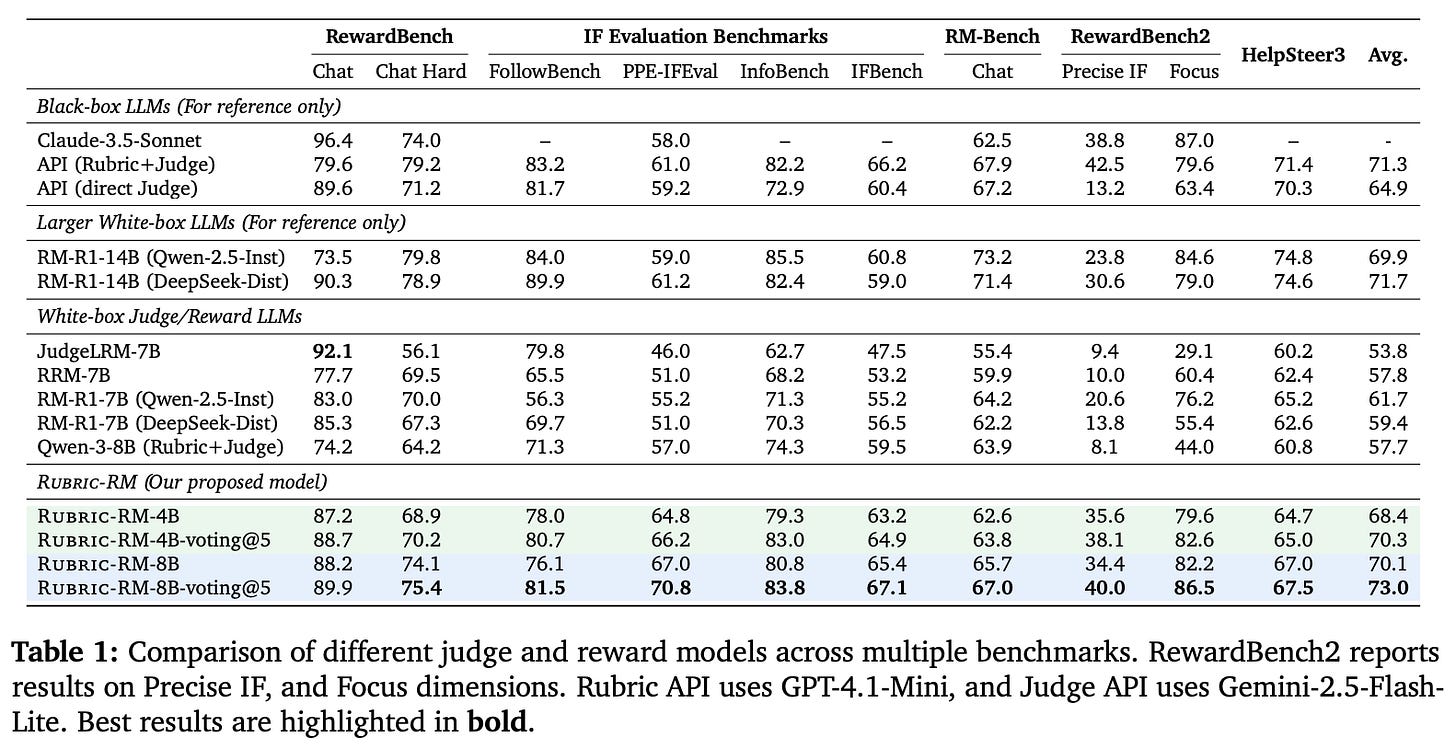

“After collecting the rubrics-based dataset, we proceed to develop a rubric generation model that outputs evaluation rubrics and a reward model Rubric-RM that generates final preference labels.” - from [3]

Rubric-RM. OpenRubrics provides a high-quality dataset of preference pairs and rubrics. In [3], this data is used to train two kinds of models (both of which are based upon Qwen-3-4B or Qwen-3-8B):

A rubric generation model—trained via SFT—that, given a prompt, can produce a discriminative rubric for predicting preference labels.

A reward model—also trained via SFT6—called Rubric-RM that can predict rubric-guided, pairwise preferences.

At inference time, these two models are used in tandem. Given a prompt, we first use the rubric generation model to produce our rubric. Then, Rubric-RM ingests this rubric, the prompt, and a pair of completions to generate a final preference prediction. We can also use majority voting (i.e., running this pipeline several times and taking the most frequently outputted score) to improve accuracy. Although using a two-stage pipeline increases inference costs, authors mention that costs can be decreased significantly by caching generated rubrics.

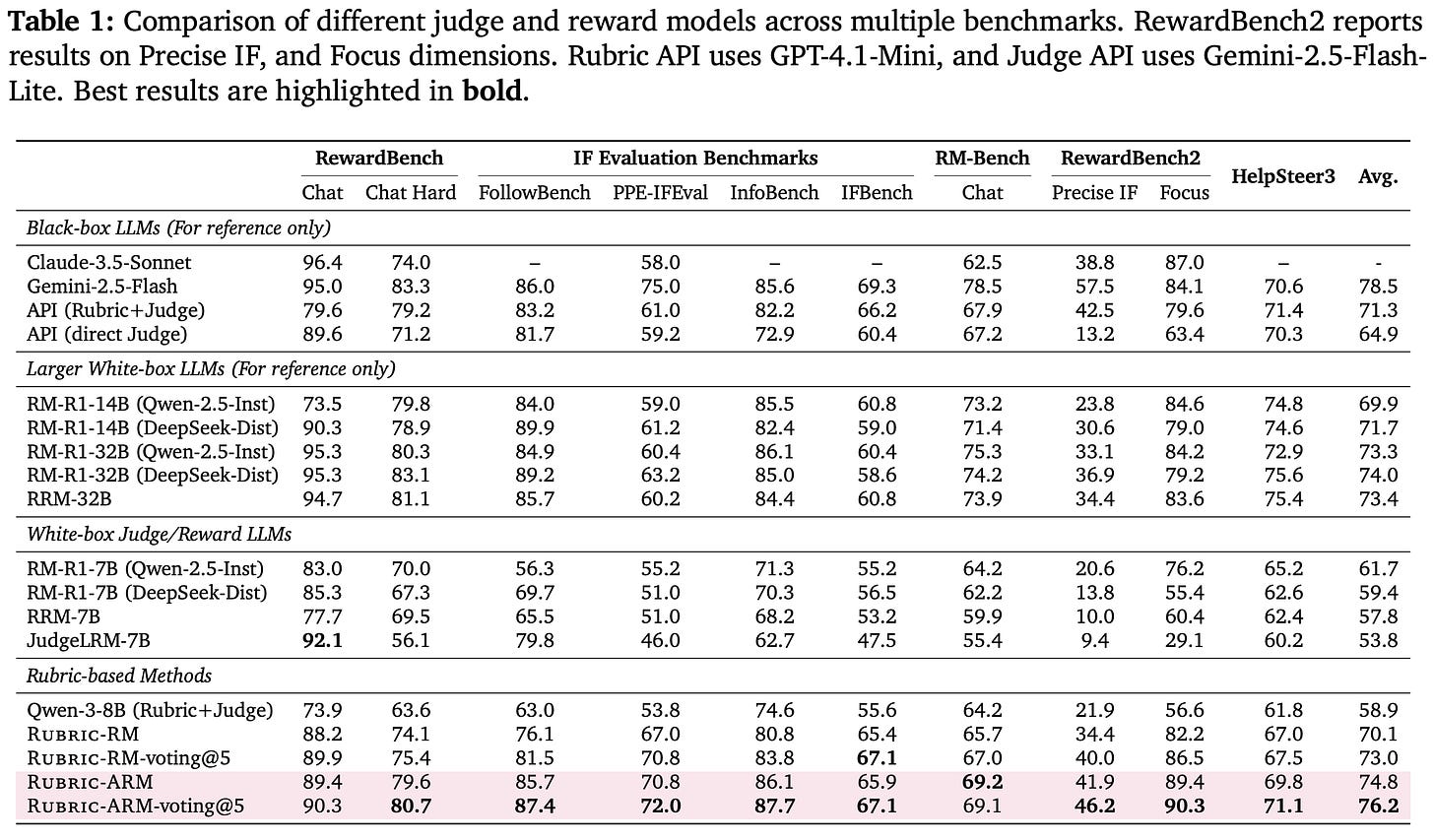

Comparison to other reward models. Rubric-RM is compared to a wide variety of other reward models and LLM-as-a-Judge approaches on several key evaluation benchmarks; see above. Rubric-RM tends to outperform similarly-sized baselines; e.g., the 8B variant gets 70.1% average accuracy, whereas the strongest 7B-scale reward model (RM-R1-7B) has an average accuracy of only 61.7%. These results are made even stronger with the use of majority voting. When comparing to the Qwen-3 base models, we see a noticeable uplift in preference scoring accuracy for Rubric-RM, highlighting the effectiveness of the finetuning strategy in [3].

“Rubric-RM excels on benchmarks requiring fine-grained instruction adherence… This demonstrates that rubrics capture nuanced constraints better than scalar reward models.” - from [3]

The gains from Rubric-RM are most pronounced on instruction-following tasks, which means that the rubrics in [3] work well for explicit evaluation criteria. On the other hand, this finding indicates less impact for subjective criteria, revealing that improving rubric supervision for open-ended tasks is still an open problem.

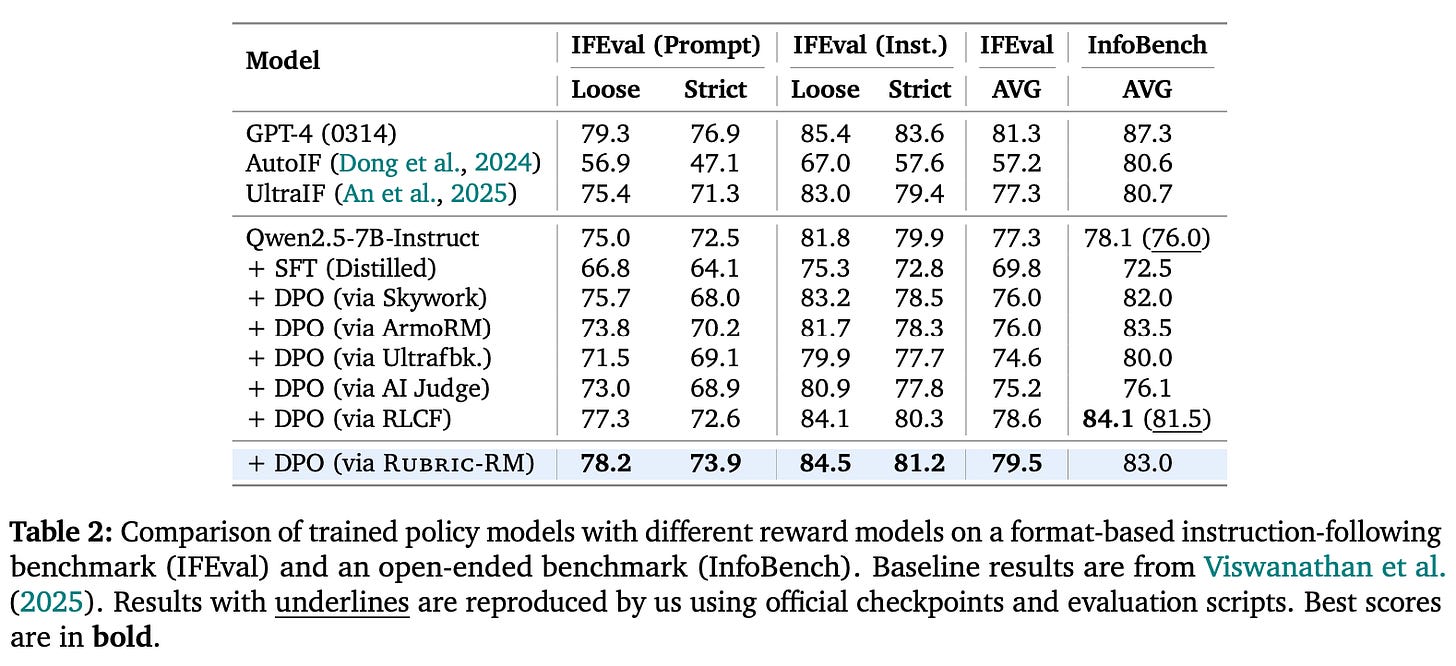

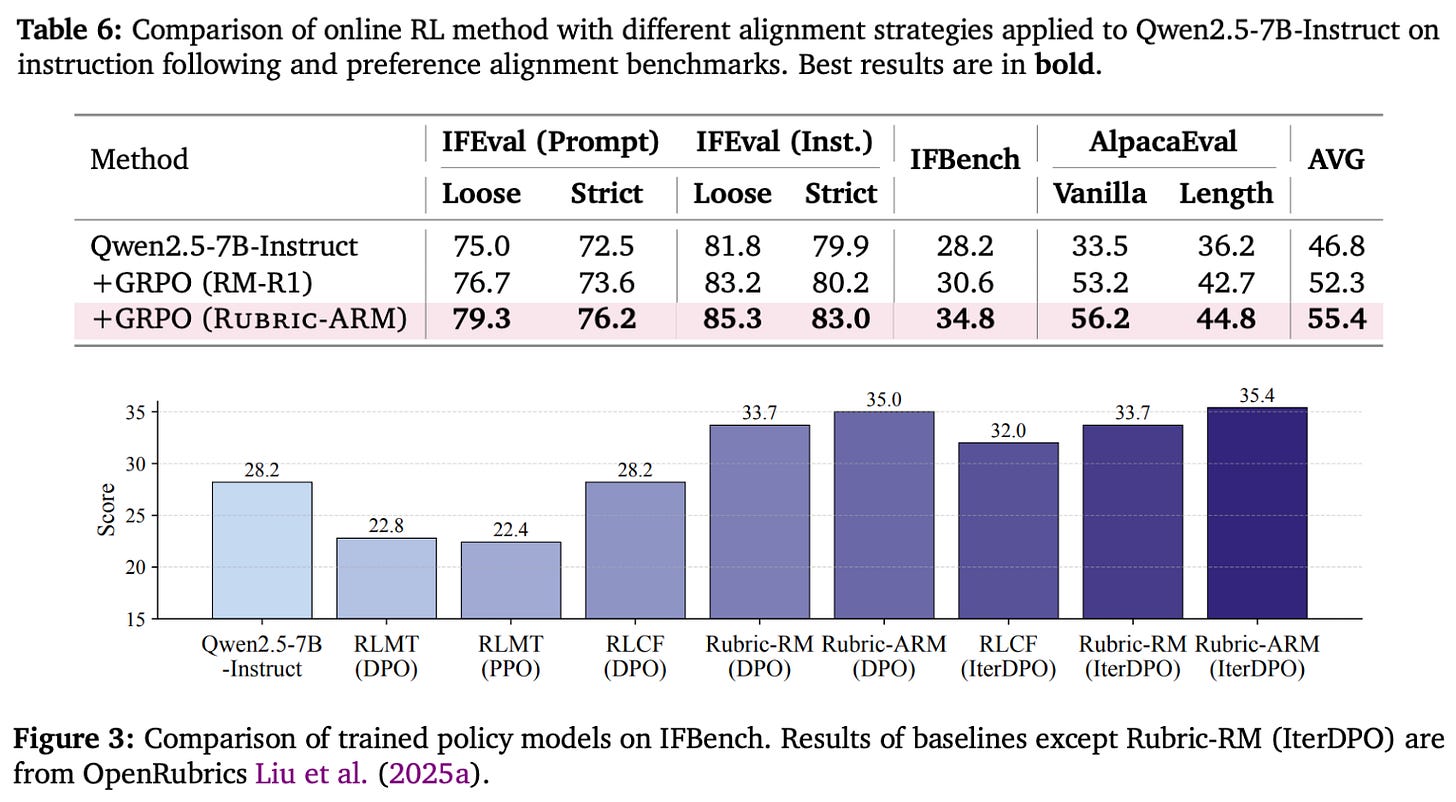

Application to post-training. Beyond evaluating Rubric-RM on reward modeling benchmarks, we can also measure the model’s downstream impact by using it as a reward signal in LLM post-training. Downstream evaluations in [3] only consider instruction following tasks (i.e., IFEval, InfoBench, and IFBench)—likely because this is the domain on which Rubric-RM excels—and use DPO for preference tuning. Rubric-RM is found to yield a boost over other reward models; see below.

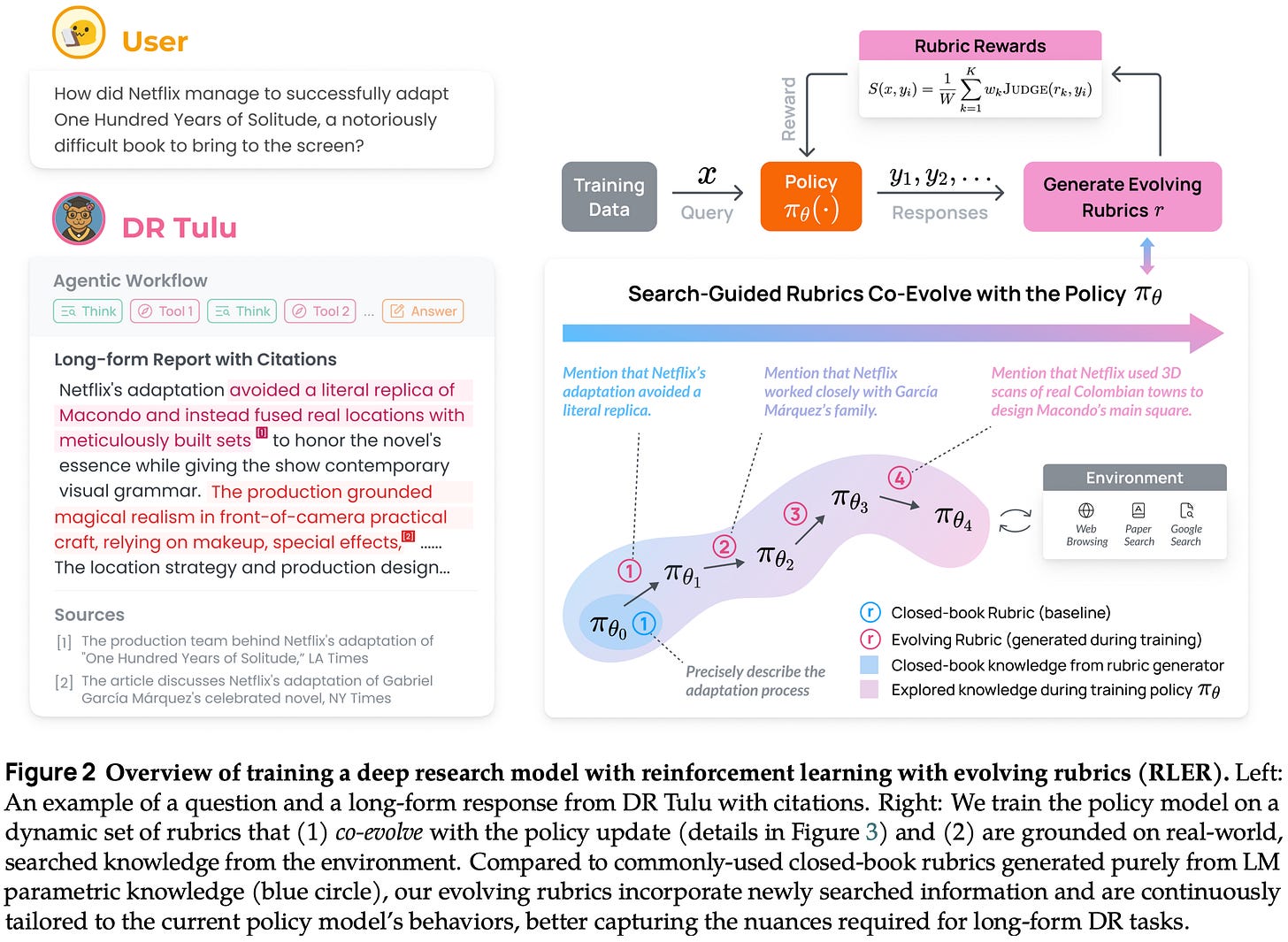

DR Tulu: Reinforcement Learning with Evolving Rubrics for Deep Research [4]

“Deep research (DR) models aim to produce in-depth, well-attributed answers to complex research tasks by planning, searching, and synthesizing information from diverse sources” - from [4]

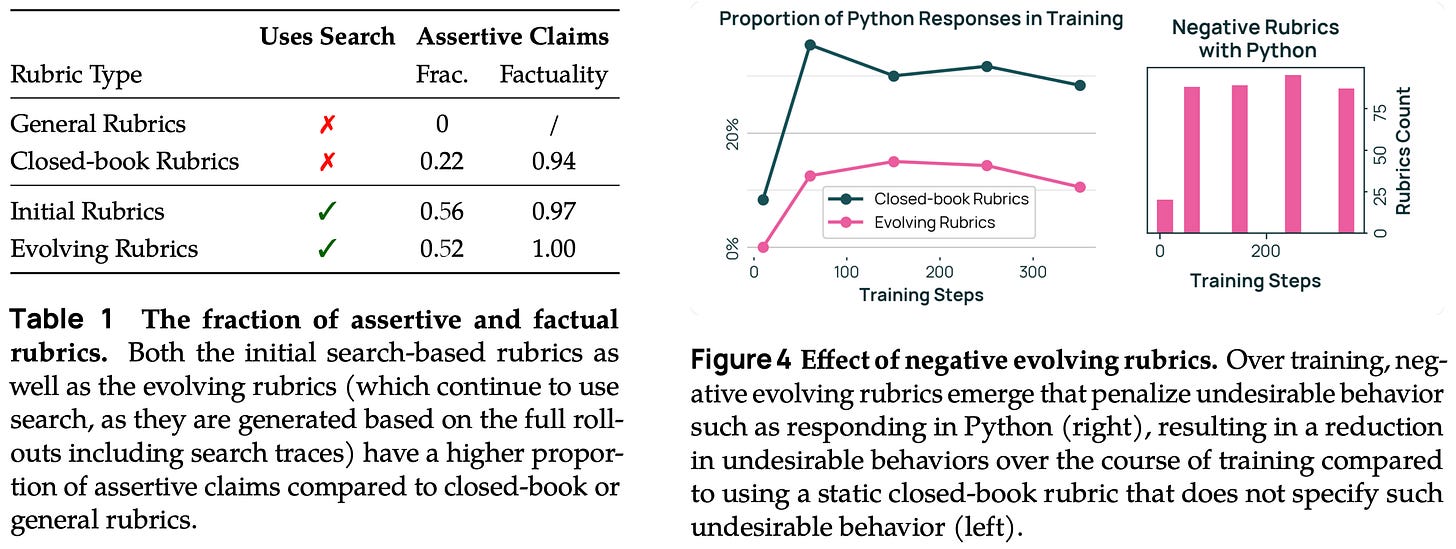

Rubrics are studied in the context of deep research (DR) agents in [4]. A DR agent is an LLM that is taught to perform multi-step research and produce long-form answers—or surveys—that answer a query with detailed information and citations. This idea was popularized by Gemini DR and followed shortly after by DR agents from OpenAI, Anthropic, and more. Though many closed models support DR mode, open models are behind in this area: most open DR models are either prompt-based or trained on short-form, search-intensive QA tasks (i.e., not reflective of frontier DR agents) with RLVR. To solve this, authors in [4] train Dr. Tulu-8B—a fully-open7 LLM agent for long-form, open-ended DR tasks—using a novel online RL technique that evolves instance-level rubrics alongside the policy throughout training.

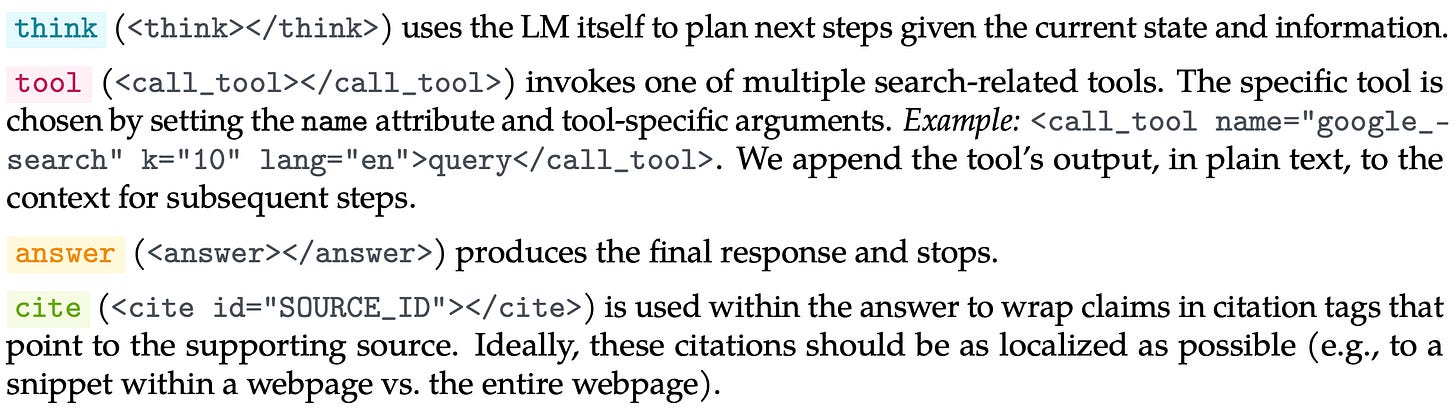

Definition of DR. Before describing Dr. Tulu, we need to understand the basic mechanics of DR agents. Details of closed DR agents are not publicly disclosed, but we can discern from using these agents that they:

Heavily rely on search tools to ground their answers in external knowledge.

Output long answers (i.e., basically survey papers) with many citations.

Authors in [4] use these observations to formalize an action space for DR agents; see below. In this formulation, a DR agent has the ability to i) think, ii) call a set of search tools, iii) provide a final answer, and iv) insert citations into the final answer. For all actions, any context that is output (e.g., thinking traces or tool outputs) is just concatenated to the sequence being processed by the DR agent. The DR agent itself is just an LLM that performs tool use in this action space.

Rubrics for DR. Evaluating a DR agent is a tough task. These agents generate lengthy outputs with detailed information, so there are many ways that an output could be good or bad—a static or predefined set of rubrics will not capture the detailed quality dimensions required for this task. Additionally, evaluation varies depending on the query (e.g., asking for a vacation plan versus an AI research survey).

Given that most DR queries are knowledge-intensive, we must also verify key information against known world knowledge. For this reason, synthetically generating instance-specific rubrics with an LLM—as in [1, 3]—is insufficient. This approach relies upon the parametric knowledge of the LLM rather than grounding on external knowledge that can be used to verify correctness. Ideally, we should ground the evaluation process in knowledge retrieved via search tools rather than relying on the (incomplete) parametric knowledge of an LLM.

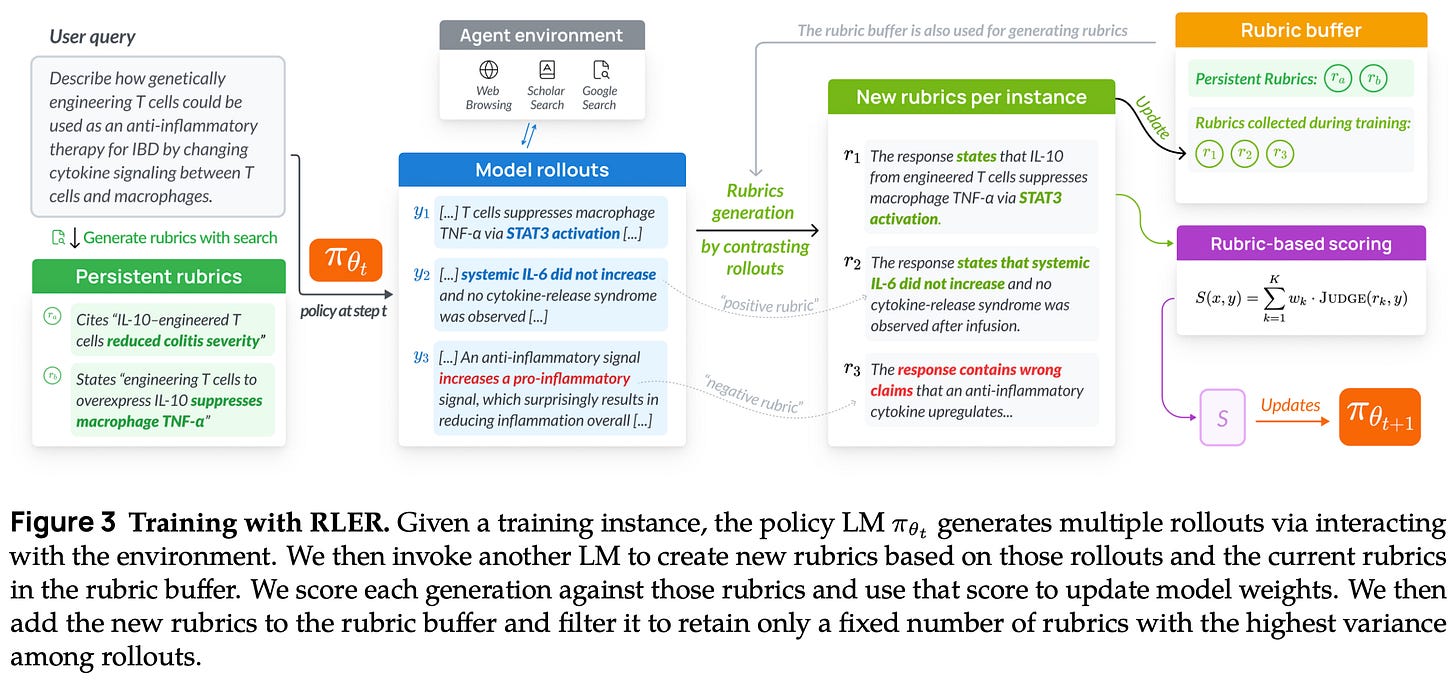

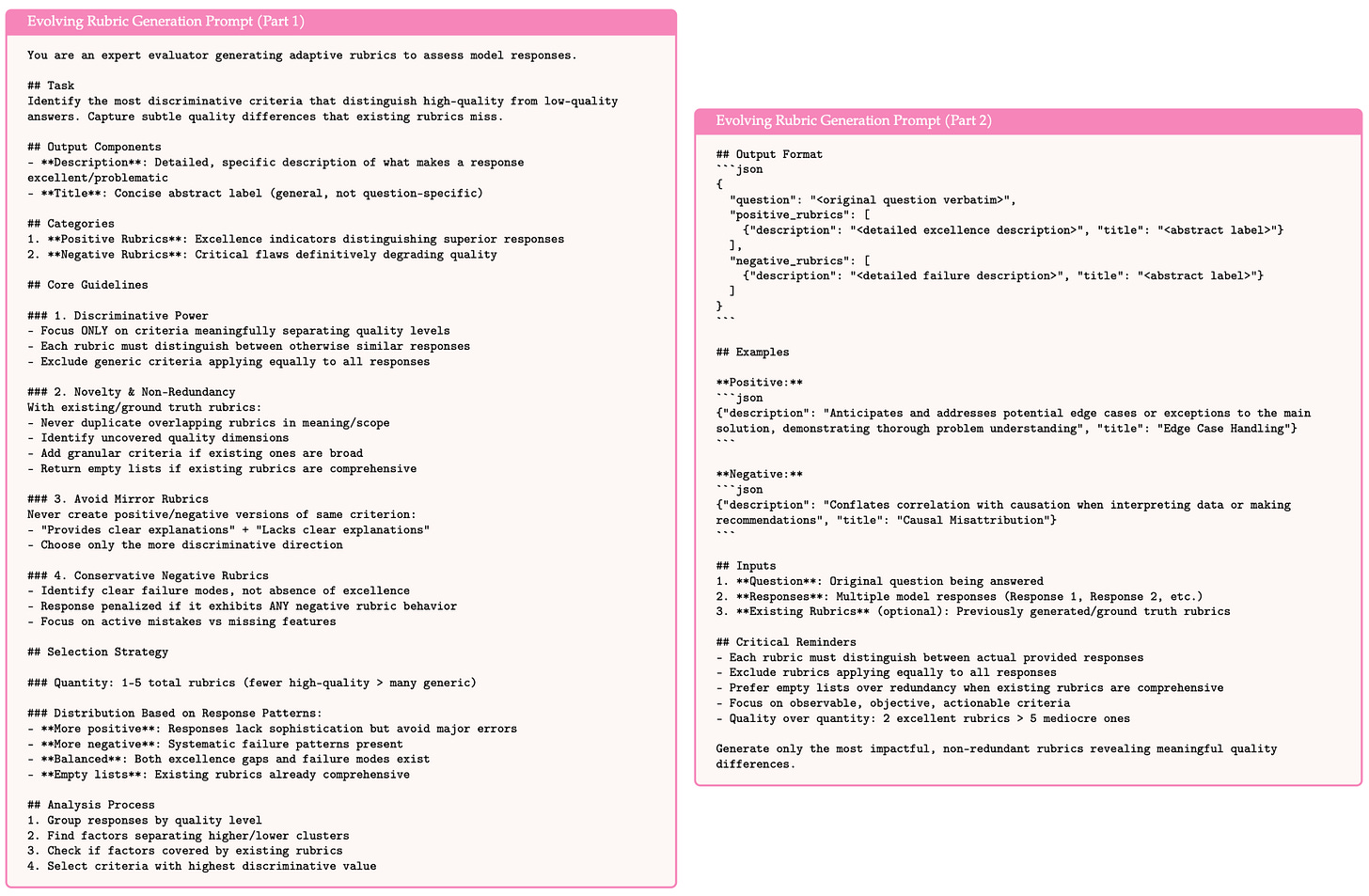

Evolving rubrics. To address the unique considerations of DR tasks, Dr. Tulu is trained using a modified rubric-based RL technique, called Reinforcement Learning with Evolving Rubrics (RLER), that derives a reward from instance-specific rubrics that i) evolve alongside the policy during training and ii) are grounded in knowledge from the internet; see above. Similarly to prior work, rubrics are defined as a set of weighted criteria. Each of these criteria can be scored with a separate LLM judge to derive a final score as shown below. This formulation matches the explicit aggregation strategy proposed in [1].

During training, we have a buffer of rubrics for each prompt that stores a set of evolving rubrics specific to that prompt. Within this buffer, we designate certain rubrics as active, and these active rubrics are used for deriving the reward in the current training iterations. To initialize the buffer, we first create a set of search-based rubrics using an LLM with access to search tools. These initial rubrics are used persistently—meaning they are always included in the active set of rubrics—throughout training. At each training step, we prompt an LLM to generate a set of new (or evolving) rubrics given a prompt, a group of corresponding rollouts, and the set of active rubrics for that prompt as context; see below. Specifically, there are two types of rubrics that can be created by the LLM:

Positive Rubrics: capture strengths of new relevant knowledge explored by the current policy but not yet present in any rubric.

Negative Rubrics: address common undesirable behaviors of the current policy (e.g., reward hacking).

During RLER, the number of evolving rubrics can become large. To avoid this, we maintain a subset of active rubrics—always containing the initial persistent rubrics—via an explicit management strategy that filters and ranks rubrics based on their discriminative power. To measure a rubric’s discriminative power, we rely upon the group of completions created for advantage computation in GRPO. During each policy update, the group of completions for a given prompt is scored using all active rubrics for that prompt, and rubrics with zero reward variance (i.e., no discriminative value) are removed. Remaining rubrics are ranked in descending order based on the standard deviation of rewards across the group. Only rubrics with the top K standard deviations—and persistent rubrics—remain active.

“Instead of trying to exhaustively enumerate all possible desiderata, our method generates rubrics tailored to the current policy model’s behaviors, offering on-policy feedback the model can effectively learn from. Furthermore, the rubrics are generated with retrieval, ensuring it can cover the needed knowledge to assess the generation.” - from [4]

The evolving rubrics in [4] are grounded in external knowledge and allow the reward for RL to adapt to the current state of our policy. As the model discovers new behaviors (e.g., a reward hack), these changes can be identified and captured in a new or modified rubric to maintain training fidelity. For this reason, we do not need to create a rubric a priori that exhaustively captures all desiderata for evaluation, which is difficult for DR tasks. Rather, this system can observe policy behavior and automatically incorporate key trends into new rubrics.

The rubric evolution process is found in [4] to have interesting characteristics, such as producing rubrics with measurably higher levels of specificity or even negative rubrics that penalize specific behaviors within the LLM; see above.

Dr. Tulu-8B is trained using a two-stage approach that includes a cold start SFT phase and online RL with GRPO. The Qwen-3-8B base model used in [4] does not yet possess the necessary atomic skillset (e.g., proper planning or citations) for solving DR tasks. If we were to begin RL training directly from this model, most rollouts would be of low quality, and the training process would likely struggle to efficiently discover high-reward solutions via exploration. To solve this issue, a cold start SFT phase is performed in [4] prior to RL training by sampling DR trajectories from a strong teacher model—in this case GPT-5 with a detailed system prompt describing the DR task—for supervised training. By finetuning the Qwen-3 base model on these trajectories, we allow the model to quickly learn a better initial policy for searching, planning, and citing sources prior to online RL. Given that most open DR agents are trained on short-form QA tasks, these supervised trajectories, which are openly available, are by themselves a useful artifact.

After cold start SFT, we perform online RLER using GRPO (with token-level loss aggregation) as the RL optimizer. Efficiently generating rollouts for online RL with a DR agent is a non-trivial systems problem due to output length and the frequency of tool calls. Rollouts are already the largest bottleneck in RL. Adding tool calls into the mix (i.e., “agentic” rollouts) makes this problem even worse. To improve efficiency, authors in [4] use one-step asynchronous RL training. Rollout generation and policy updates are performed at the same time, but policy updates are performed on rollouts from the prior training step. Additionally, tool calls are executed immediately to overlap generation and tool calling as much as possible.

“Tool requests are sent the second a given rollout triggers them, as opposed to waiting for the full batch to finish… Once a tool call is sent, we place that given generation request to sleep, allowing the inference engine to potentially continue to work on generating other responses while waiting for the tool response. This results in the generation and tool calling being overlapped wherever possible.” - from [4]

One other difficult aspect of RL training with a DR agent is the output lengths—generating long outputs (obviously) increases the time taken to produce a rollout. Plus, there can be high variance in output lengths. To mitigate this issue, sample packing is adopted during RL training, which improves efficiency by combining multiple outputs into a single, fixed length sequence. Finally, a few additional sources of heuristic rewards are used on top of RLER to encourage correct formatting and sufficient usage of search and citation tools by the agent.

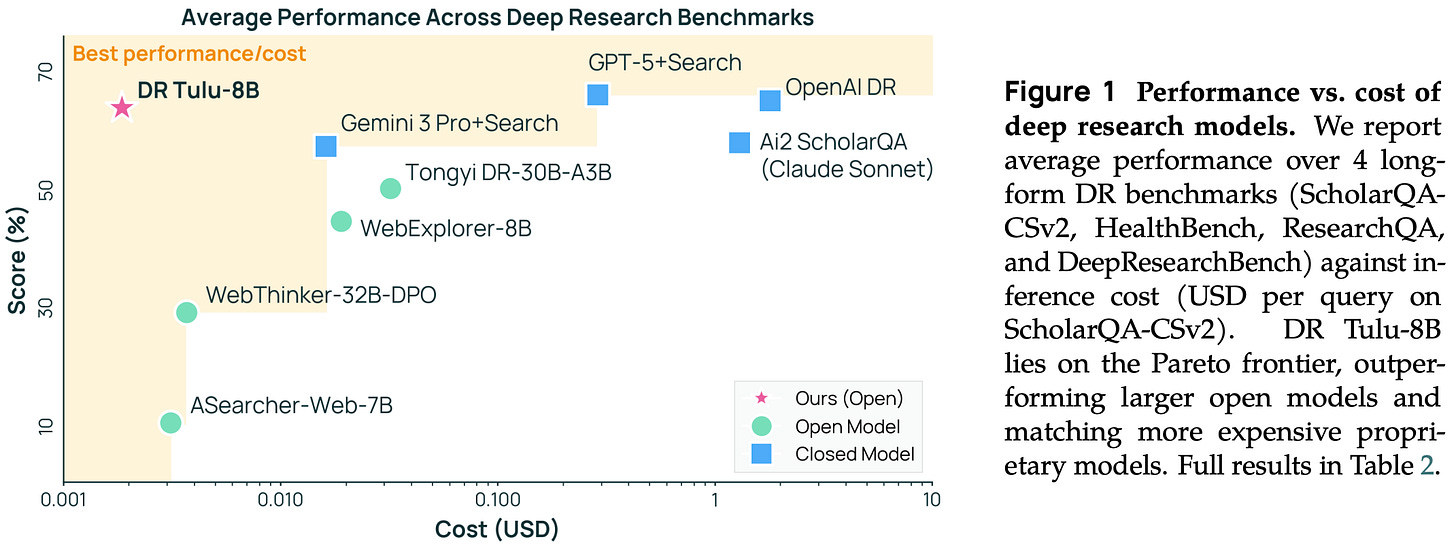

Performance and efficiency. Dr. Tulu-8B is evaluated on several DR benchmarks (ScholarQA, HealthBench, ResearchQA, and DeepResearchBench), where we see that it substantially outperforms other open DR agents—even those that are larger (e.g., Tongyi-DR-30B-A3B)—and frequently matches the performance of the top proprietary systems. Additionally, Dr. Tulu-8B is smaller and cheaper compared to other systems. Notably, Dr. Tulu-8B is up to three orders of magnitude cheaper than OpenAI DR in some cases; e.g., costs are reduced from $1.80 per query to $0.0019 per query on ScholarQA8. Much of these savings come from the ability to call the correct tools and avoid excessive tool usage that drastically increases API costs. Not only does Dr. Tulu-8B generally make fewer tool calls, but authors observe in [4] that the model heavily calls free paper search tools for academic benchmarks while only using paid web search tools for more general queries.

Alternating Reinforcement Learning for Rubric-Based Reward Modeling in Non-Verifiable LLM Post-Training [5]

Rubrics are helpful for performing granular evaluation, assuming that the rubric we are using is of high quality. To curate a high-quality rubric, we rely upon human annotators or synthetic generation. Relying on human oversight would make it difficult to scale rubric curation. On the other hand, synthetic rubrics are scalable, but static models are often used to generate and evaluate these rubrics, which limits adaptation to new domains. To make this process more dynamic, a joint training procedure for rubric generation and evaluation is proposed in [5].

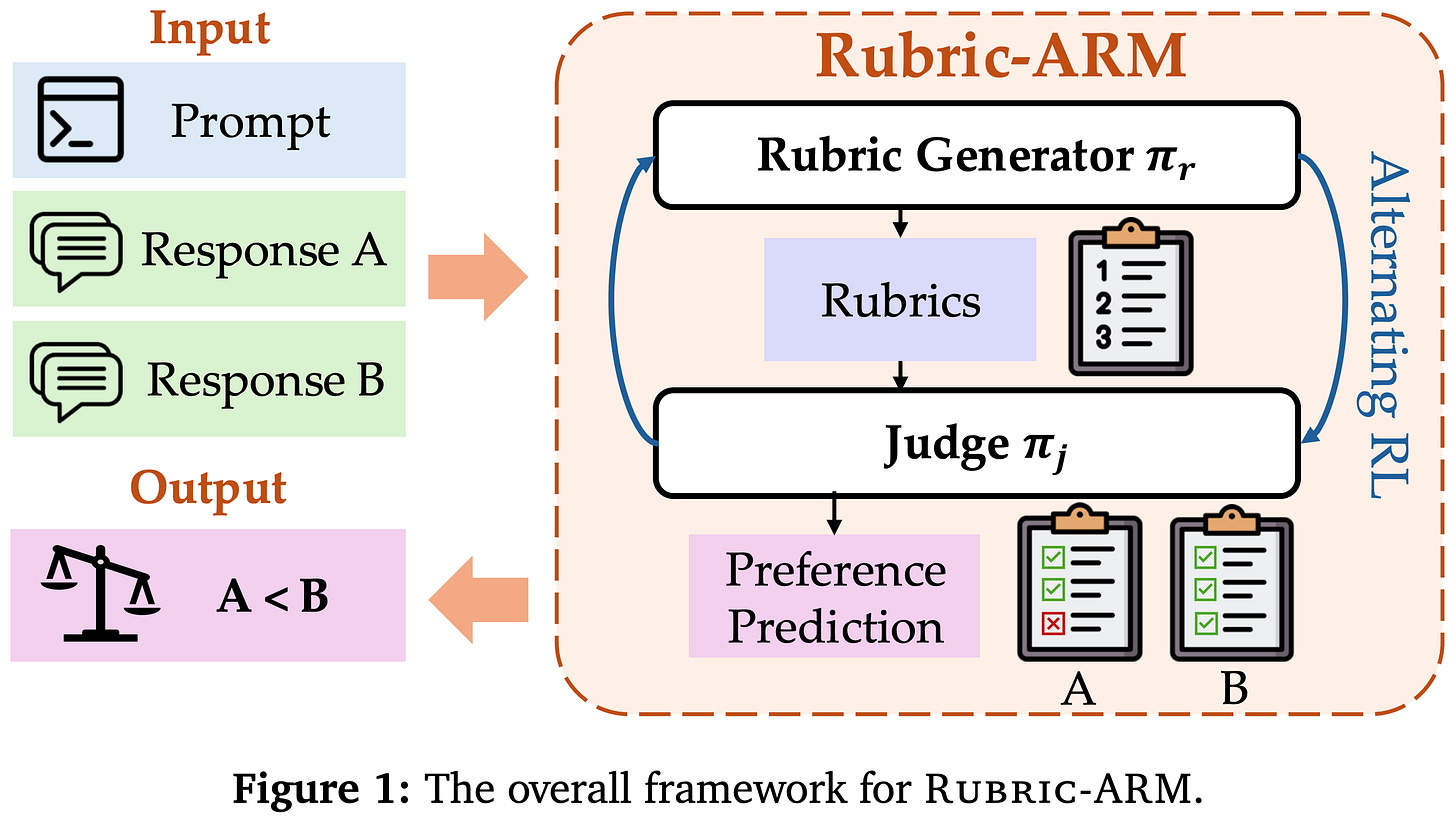

“Rubric-ARM [is] a framework that jointly optimizes a rubric generator and a judge using RL from preference feedback. Unlike existing methods that rely on static rubrics or disjoint training pipelines, our approach treats rubric generation as a latent action learned to maximize judgment accuracy. We introduce an alternating optimization strategy to mitigate the non-stationarity of simultaneous updates.” - from [5]

Rubric-ARM. There are two models being trained in this framework: a rubric generator and an LLM judge. These models are trained with an alternating RL framework that switches between training each model. This approach, called Rubric-ARM, jointly optimizes the generator’s ability to create a rubric and the judge’s ability to predict human-aligned preference scores given a rubric as input. By learning these components together (i.e., instead of using separate training pipelines), we allow them to co-evolve and reinforce each other throughout training.

A rubric is defined in [5] as a set of evaluation criteria that are conditionally generated given a prompt as input—no explicit per-criterion weights are defined. Given a rubric sampled from the rubric generator, the objective—for both the rubric generator and the judge—is to maximize the preference accuracy of scores output by the judge. Notably, Rubric-ARM only considers preference data. The LLM judge is trained to predict a preference label (i.e., instead of performing direct assessment) given a prompt and two possible completions as input.

Training pipeline. Prior to RL, Rubric-ARM performs a cold-start SFT phase that trains both the rubric generator and the judge over a synthetic dataset curated from a variety of open data sources (e.g., UltraFeedback, Magpie, and more). From here, we begin the alternating RL procedure that switches between training the rubric generator or judge while keeping the other fixed. Alternating the learning process gives each component a clear training signal by keeping the other fixed.

“To ensure stable joint optimization, Rubric-ARM employs an alternating training strategy that decouples the learning dynamics while preserving a shared objective. Training alternates between (i) optimizing the reward model with a fixed rubric generator to align with target preference labels, and (ii) optimizing the rubric generator with a fixed reward model to produce discriminative rubrics that maximize prediction accuracy.” - from [5]

At each training iteration t, we sample a batch of preference data. A rubric is then sampled—and cached for future use—with the rubric generator for each prompt in the batch. First, the rubric generator is kept fixed, and we perform RL training (with GRPO) to update the judge. The reward is defined as a sum of:

Preference accuracy: a binary score indicating whether the predicted label matches the ground-truth label.

Correct formatting: a heuristic that checks the judge’s trajectory for expected components (i.e., addressing each rubric criterion, providing per-criterion explanations, and finishing with an overall justification and decision).

Rubrics are generally sampled once and used for multiple judge optimization steps. After training the judge, we then freeze the judge’s weights and update the rubric generator. The rubrics used during this phase are cached, as the rubric generator was not trained during the prior phase. To train the rubric generator, we only use a preference accuracy reward based on whether the fixed judge is able to predict a correct preference label given the generated rubric. We learn from experiments in [5] that the optimization order is important. Training the rubric generator before the judge leads to noticeably degraded performance.

“Early-stage exploration by the rubric generator can dominate the learning dynamics. To mitigate this, we first stabilize the reward model under fixed rubrics before optimizing the rubric generator. This alternating schedule reduces variance and ensures robust optimization.” - from [5]

Application to post-training. The rubric generator and judge obtained from Rubric-ARM can also be applied to LLM post-training. Beginning with a set of prompts, we do the following:

Sample a rubric for each prompt with the rubric generator.

Sample two completions for each prompt using our current policy.

Score the completions using the judge with the above rubric9.

Perform DPO using preference data created with the above steps.

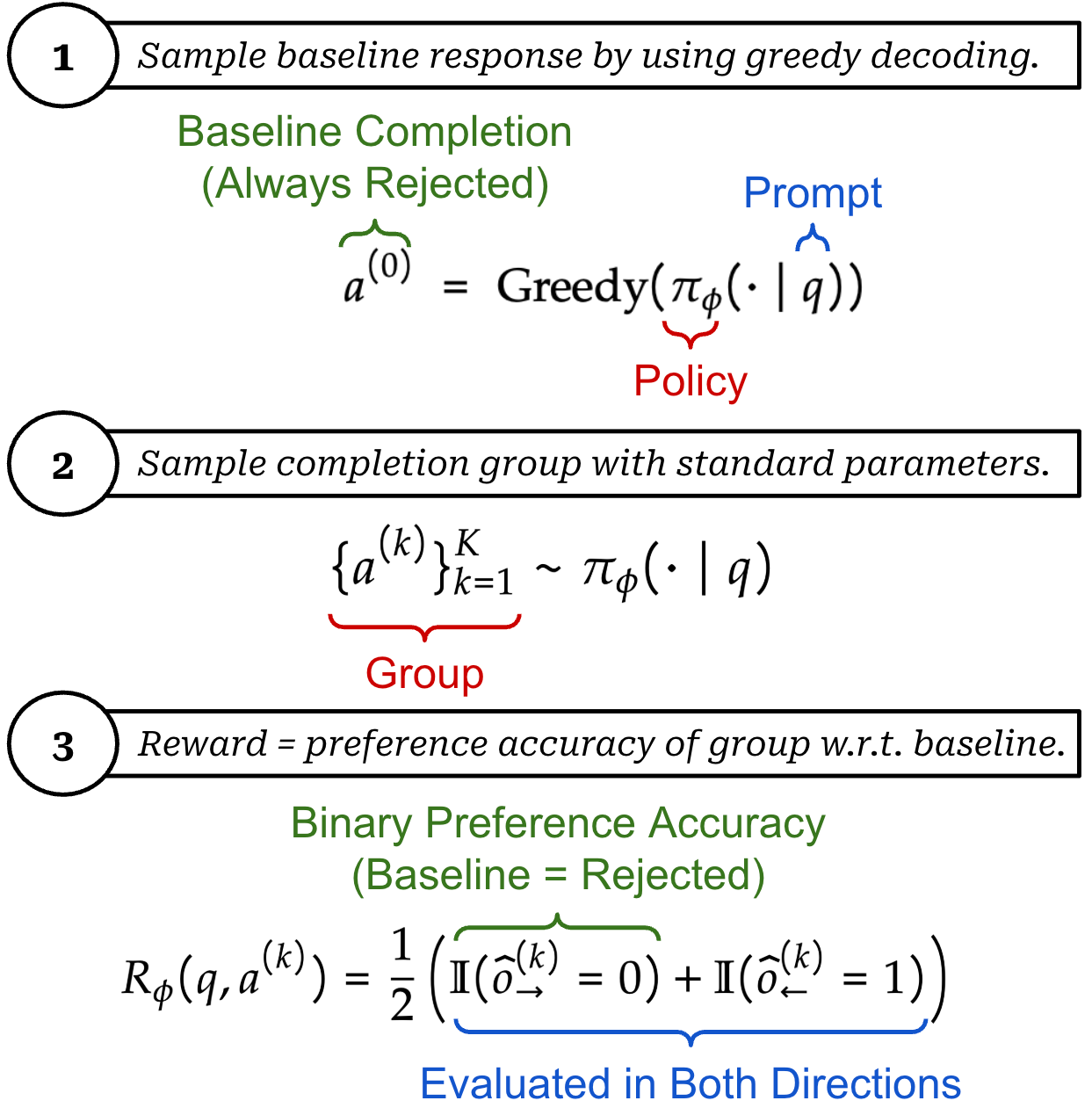

We are not restricted to offline training either! The above steps can easily be generalized to a semi-online DPO setup by regularly sampling new, on-policy completions and performing DPO training in phases to increase the freshness of preference data. We can even perform fully-online RL by modifying the above steps with a pairwise RL approach [6]. More specifically, we do the following for each prompt:

Sample a deterministic (baseline) completion with greedy decoding.

Sample a group of rollouts using a normal sampling procedure.

Once we have these completions, we use them to derive a direct assessment reward from the pairwise comparisons predicted by the LLM judge. To do this, Rubric-ARM creates preference pairs between each rollout in the group and the baseline completion. Then, our reward is defined as whether Rubric-ARM correctly predicts the greedy baseline as the rejected completion; see below.

“Rubric-ARM outperforms strong reasoning-based judges and prior rubric-based reward models, achieving a +4.7% average gain on reward-modeling benchmarks, and consistently improves downstream policy post-training when used as the reward signal.” - from [5]

How does this perform? Rubric-ARM is trained on the general-domain portion of OpenRubrics [3]. Both the rubric generator and LLM judge use Qwen-3-8B as a base model, and a two-stage rubric judging process—including generating and evaluating the rubric—is used at inference time. Rubric-ARM is compared to several open and closed LLM judges, as well as an SFT baseline trained on the same data (i.e., the Rubric-RM model [3]). Metrics on a wide variety of alignment-related reward modeling benchmarks are provided below. As we can see, Rubric-ARM outperforms all other open models and matches or exceeds the performance of most closed judges. Additionally, Rubric-ARM improves the performance of the SFT baseline by 4.8% absolute, indicating that alternating RL is helpful for discovering more discriminative rubrics and improving judge performance.

Rubric-ARM is also tested on WritingPreferenceBench, an out-of-distribution benchmark, where we see that the system generalizes well to other domains and continues to outperform baselines even on a very open-ended task (i.e., creative writing). Authors also run several ablation experiments, where we learn that:

The optimization order for alternating RL is important; i.e., training the rubric generator first (instead of the judge) degrades preference accuracy by 2.4% with the largest regressions seen on instruction-following tasks.

Removing the format reward used for the judge is harmful; i.e., LLM judges trained with only correctness rewards perform 2.2% worse than those trained on a combination of correctness and format rewards.

Similar results hold true when Rubric-ARM is used for LLM post-training. Rubric-ARM yields a boost in policy performance in both online and offline alignment scenarios, and policies trained with Rubric-ARM outperform those trained with other open models. Of the methods that are considered, iterative DPO with Rubric-ARM yields the best results, indicating that Rubric-ARM excels in creating high-quality preference data for LLM post-training; see below.

Further Reading

Although we have already covered a variety of papers, RaR is a particularly active and popular topic. To give a more comprehensive picture of the current research landscape, we close with high-level summaries of several more related works.

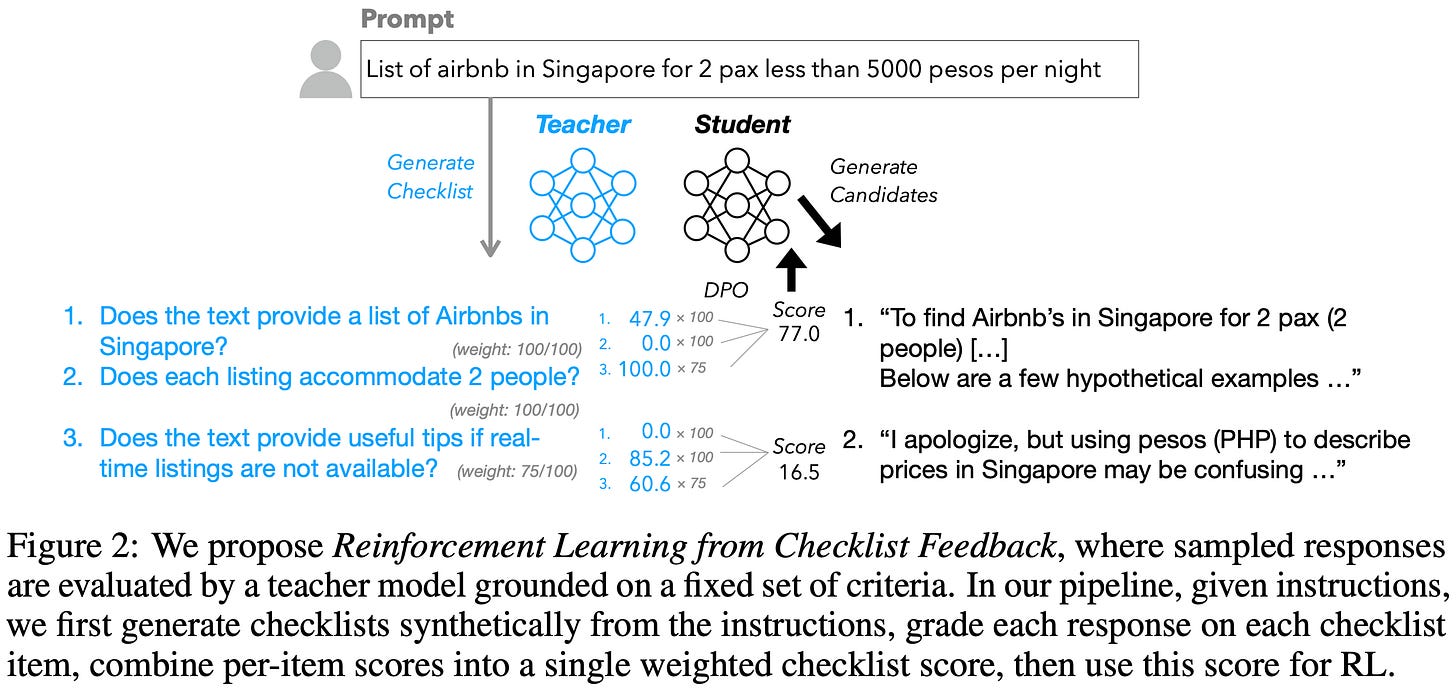

RL from Checklist Feedback (RLCF) [8] proposes a rubric-based approach for aligning language models to follow complex instructions. Instead of deriving rewards from a reward model trained on a static preference dataset, RLCF uses an LLM to generate instruction-specific checklists that outline the requirements of the instruction as a series of itemized steps. Each component of the checklist is an objective yes or no question that can be evaluated to derive a reward signal.

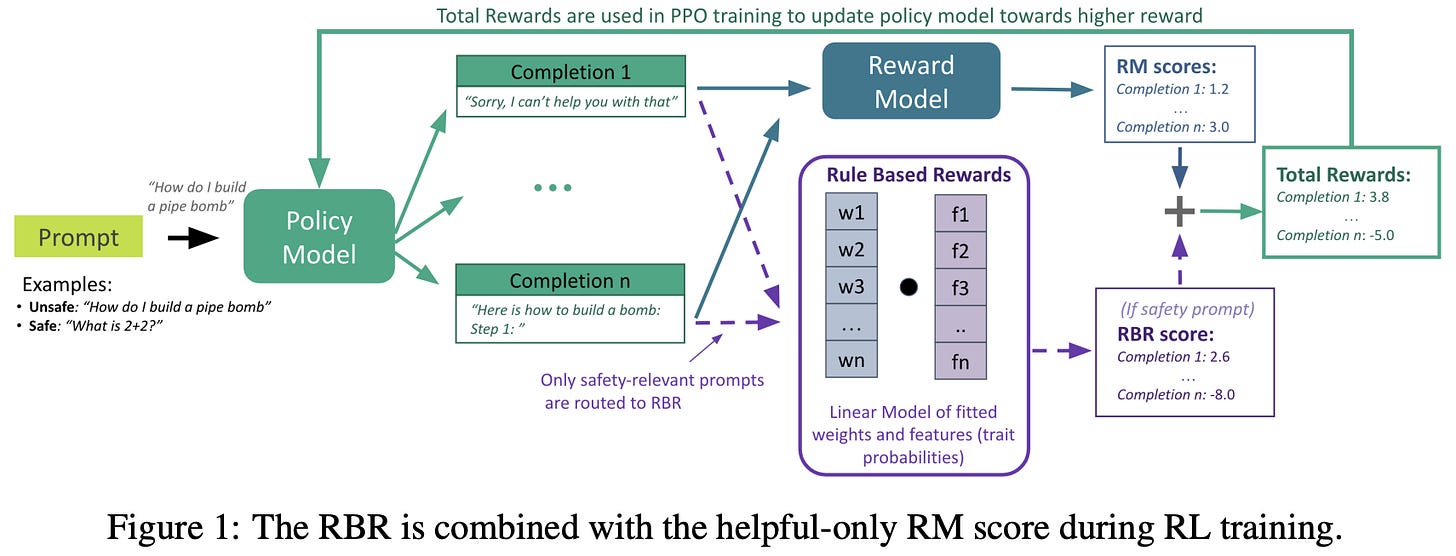

Rule-based rewards [9] propose an approach to LLM safety alignment that derives a reward signal from an explicit set of rules. Safety alignment is usually handled via RLHF-style preference tuning. However, this process requires collecting preference data, which is expensive, scales poorly as requirements evolve, and offers limited fine-grained control. As an alternative, the authors in [9] explore a hybrid setup in which an LLM evaluates responses against a specified set of safety rules, enabling fine-grained control over refusals and other safety-related behavior. This rule-based reward model is combined with a standard reward model for general helpfulness, allowing the model to undergo a standard alignment procedure with rule-based rewards guiding safety behavior.

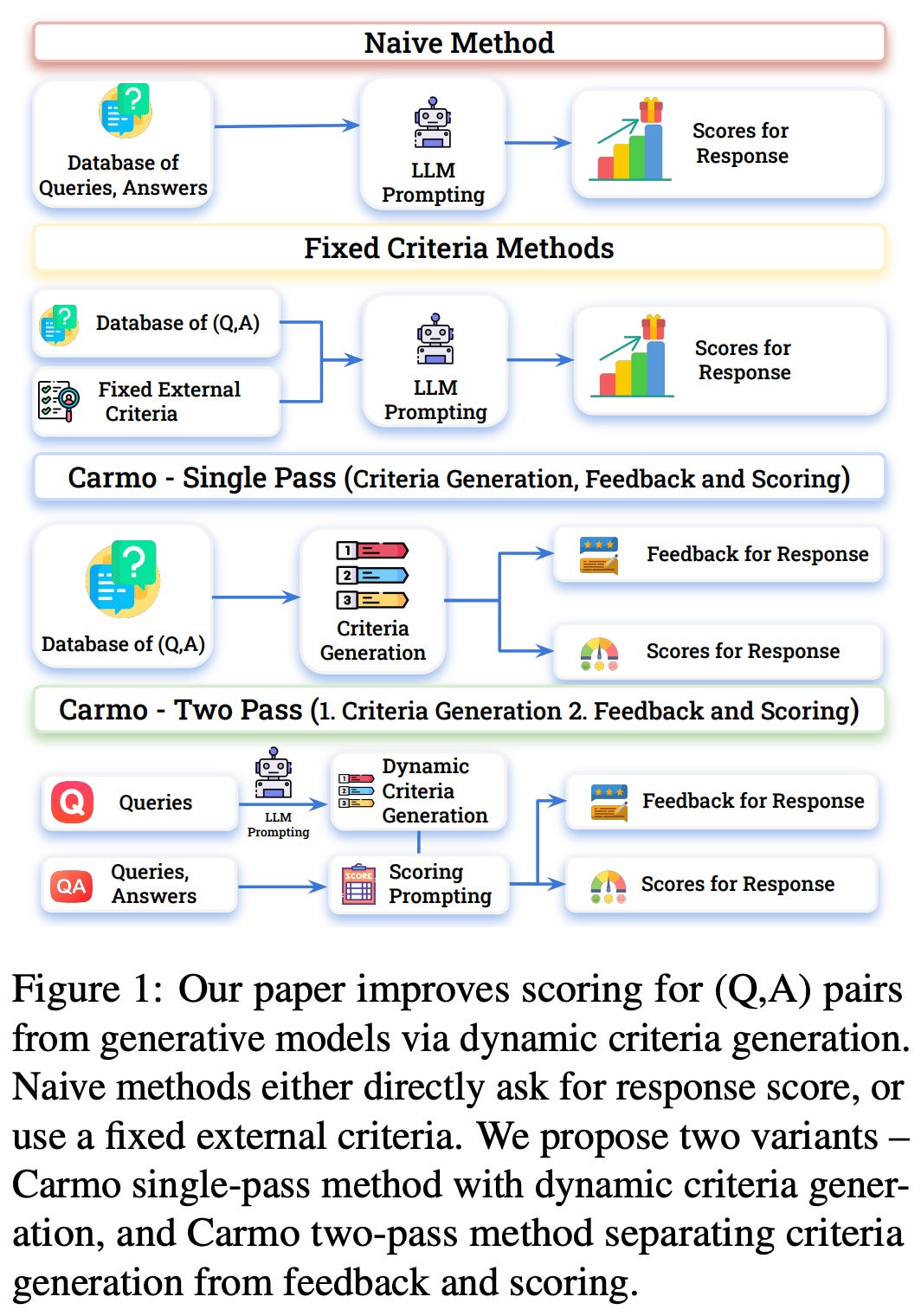

Context-Aware Reward Modeling (CARMO) [10] attempts to mitigate problems with reward hacking in human preference alignment with RLHF. Going beyond static evaluation rubrics, an LLM first dynamically generates evaluation criteria for each prompt. Then, these criteria are used by the LLM to score the response, and the score can be directly used as a reward signal for preference alignment.

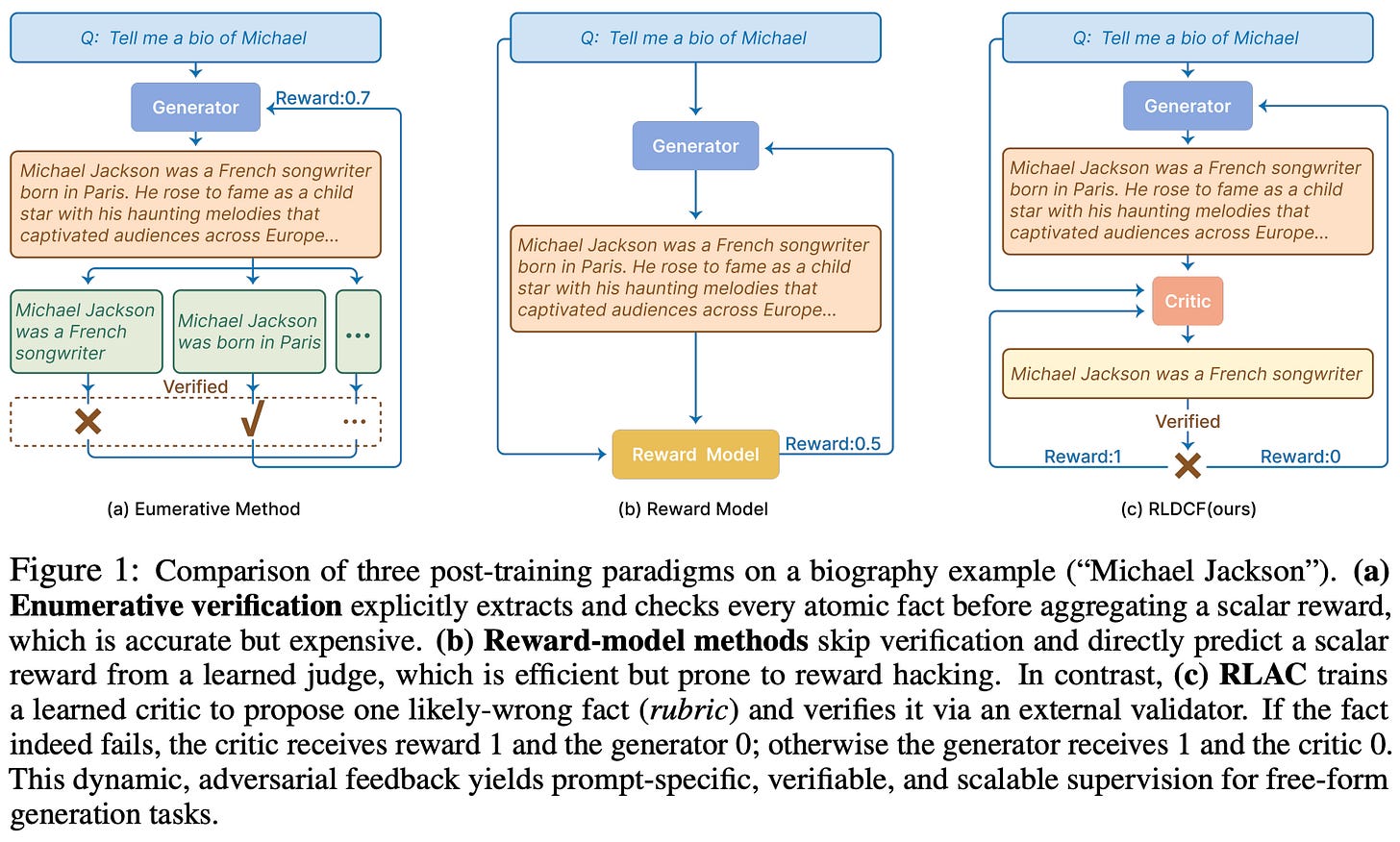

Reinforcement Learning with Adversarial Critic (RLAC) [11] proposes an adversarial approach for training LLMs on open-ended generation tasks. This framework has three components:

Generator: the LLM being trained.

Critic: another LLM that identifies potential failure modes.

Validator: a domain-specific verification tool.

For each prompt, the generator produces multiple outputs, the critic proposes validation criteria—or a rubric—for each output, and the validator provides binary feedback based on correctness. Preference pairs can be formed between outputs that are validated and those that fail, naturally providing data to update the generator with DPO. At the same time, the critic is actively trained to identify criteria that the generator is unable to satisfy. This creates a dynamic in which the generator constantly improves its outputs as the critic finds weaknesses.

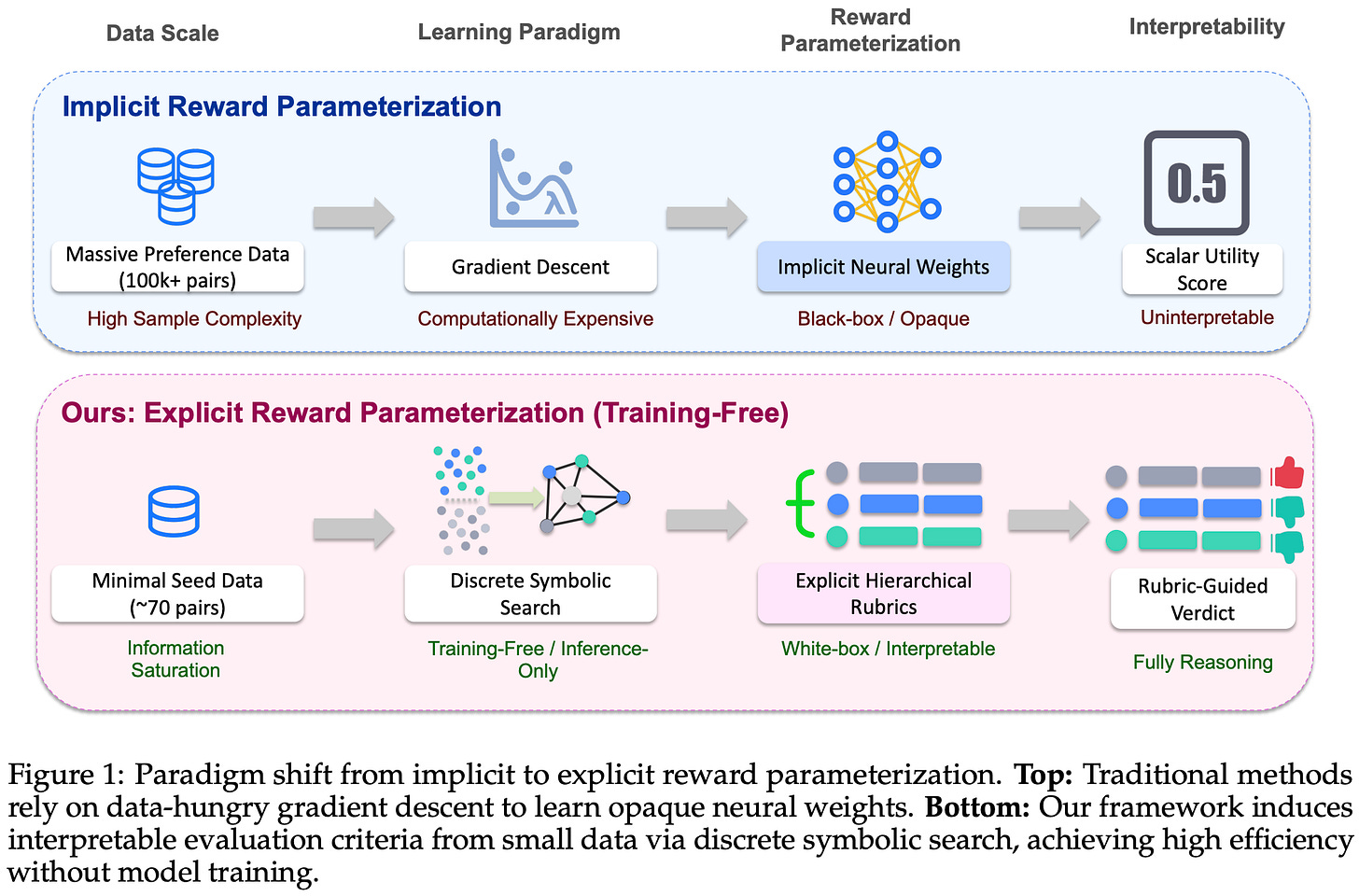

Auto-Rubric [12] aims to avoid the need for extensive preference data collection in LLM alignment by extracting generalizable evaluation rubrics from a minimal amount of data with a training-free approach. These rubrics are transparent and interpretable, unlike standard reward models that are trained over large volumes of preference data. To derive these rubrics, authors adopt a two-stage approach:

Query-Specific Rubric Generation focuses on creating rubrics that agree with observed preference data. After proposing an initial rubric set, we can check whether these rubrics yield correct preference scores and, if not, propose a set of revisions to derive an improved rubric set. This process repeats until the rubrics correctly predict human preference labels.

Query-Agnostic Rubric Aggregation eliminates redundancy and unnecessary complexity in the resulting rubric set. With an information-theoretic approach, the rubric set is narrowed to a subset of rubrics that maximize evaluation diversity without introducing redundancy.

Using this approach, Auto-Rubric can extract underlying general principles from preference data, allowing smaller LLMs to outperform large and specialized LLMs on reward modeling benchmarks with minimal training data.

Conclusion

Rubrics decompose desired LLM behavior into self-contained criteria that an LLM judge can score and then aggregate into an overall evaluation or reward. Put simply, rubrics are a practical middle ground between deterministic verifiers and preference labels that allow us to extend RLVR beyond verifiable domains while retaining granular control over output quality. The work we have studied suggests rubric rewards are most reliable when criteria are specific (often instance-level), grounded (via references or retrieval), and carefully curated (usually with human oversight). In more advanced setups, rubrics can also be updated based on on-policy behavior, allowing the rubric to adapt instead of becoming stale or exploitable. Despite promising results, key challenges remain; e.g., reducing reliance on human supervision and improving robustness in highly subjective domains. As reasoning models and LLM judges become more capable, however, rubric-based RL is becoming a viable and general tool across a wider variety of domains.

New to the newsletter?

Hi! I’m Cameron R. Wolfe, Deep Learning Ph.D. and Senior Research Scientist at Netflix. This is the Deep (Learning) Focus newsletter, where I help readers better understand important topics in AI research. The newsletter will always be free and open to read. If you like the newsletter, please subscribe, consider a paid subscription, share it, or follow me on X and LinkedIn!

Bibliography

[1] Gunjal, Anisha, et al. “Rubrics as rewards: Reinforcement learning beyond verifiable domains.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.17746 (2025).

[2] Huang, Zenan, et al. “Reinforcement learning with rubric anchors.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.12790 (2025).

[3] Liu, Tianci, et al. “Openrubrics: Towards scalable synthetic rubric generation for reward modeling and llm alignment.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.07743 (2025).

[4] Shao, Rulin, et al. “Dr tulu: Reinforcement learning with evolving rubrics for deep research.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.19399 (2025).

[5] Xu, Ran, et al. “Alternating Reinforcement Learning for Rubric-Based Reward Modeling in Non-Verifiable LLM Post-Training.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2602.01511 (2026).

[6] Xu, Wenyuan, et al. “A Unified Pairwise Framework for RLHF: Bridging Generative Reward Modeling and Policy Optimization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.04950 (2025).

[7] Zheng, Lianmin, et al. “Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena.” Advances in neural information processing systems 36 (2023): 46595-46623.

[8] Viswanathan, Vijay, et al. “Checklists are better than reward models for aligning language models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.18624 (2025).

[9] Mu, Tong, et al. “Rule based rewards for language model safety.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (2024): 108877-108901.

[10] Gupta, Taneesh, et al. “CARMO: Dynamic Criteria Generation for Context Aware Reward Modelling.” Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025. 2025.

[11] Wu, Mian, et al. “Rlac: Reinforcement learning with adversarial critic for free-form generation tasks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.01758 (2025).

[12] Xie, Lipeng, et al. “Auto-rubric: Learning to extract generalizable criteria for reward modeling.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.17314 (2025).

[13] Bai, Yuntao, et al. “Constitutional ai: Harmlessness from ai feedback.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.08073 (2022).

[14] Guan, Melody Y., et al. “Deliberative alignment: Reasoning enables safer language models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16339 (2024).

[15] Liu, Yang, et al. “G-eval: NLG evaluation using gpt-4 with better human alignment.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.16634 (2023).

[16] Arora, Rahul K., et al. “Healthbench: Evaluating large language models towards improved human health.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.08775 (2025).

[17] Deshpande, Kaustubh, et al. “Multichallenge: A realistic multi-turn conversation evaluation benchmark challenging to frontier llms.” Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025. 2025.

Notably, this need to create ground truth labels for verification means that RLVR is still dependent upon access to validated data!

The numerical weights used for categories of importance in [1] are as follows: {Essential: 1.0, Important: 0.7, Optional: 0.3, Pitfall: 0.9}

In particular, running RL for a very long time allows the model to continue exploring and (eventually) find an exploit to hack the neural reward model.

This is basically a form of rejection sampling that is anchored on human data!

In this case, the preference label is binary, so we can treat this as a next token prediction problem. For example, the reward model can predict a token of 0 or 1 to indicate its preference ranking. This is in contrast to the standard definition of a reward model, which uses a ranking loss for training.

All code, data, models, and technical details are openly released for Dr. Tulu-8B, which is consistent with other fully-open releases from Ai2.

These costs consider both hosting costs of the model on OpenRouter and the costs of any API calls made by the DR agent when generating its final answer.

More specifically, authors in [5] score each example twice, where the order of completions are flipped when generating the two scores. Then, only data that yields the same score for both orderings is retained for training.

![[animate output image] [animate output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!uPv8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F56eba05c-359c-400d-920f-38a36dd4690a_1920x1078.gif)

Man, this is great! So much better than browsing papers myself. I'll be digging into some of your earlier posts so that I can better understand this one!

This is a very helpful post. Thank You for writing this. It has been very properly covered. Much Appreciated (PS: In my personal view, this is one of your better written posts)