A Practitioners Guide to Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

How basic techniques can be used to build powerful applications with LLMs...

The recent surge of interest in generative AI has led to a proliferation of AI assistants that can be used to solve a variety of tasks, including anything from shopping for products to searching for relevant information. All of these interesting applications are powered by modern advancements in large language models (LLMs), which are trained over vast amounts of textual information to amass a sizable knowledge base. However, LLMs have a notoriously poor ability to retrieve and manipulate the knowledge that they possess, which leads to issues like hallucination (i.e., generating incorrect information), knowledge cutoffs, and poor understanding of specialized domains. Is there a way that we can improve an LLM’s ability to access and utilize high-quality information?

“If AI assistants are to play a more useful role in everyday life, they need to be able not just to access vast quantities of information but, more importantly, to access the correct information.” - source

The answer to the above question is a definitive “yes”. In this overview, we will explore one of the most popular techniques for injecting knowledge into an LLM—retrieval augmented generation (RAG). Interestingly, RAG is both simple to implement and highly effective at integrating LLMs with external data sources. As such, it can be used to improve the factuality of an LLM, supplement the model’s knowledge with more recent information, or even build a specialized model over proprietary data without the need for extensive finetuning.

What is Retrieval Augmented Generation?

Before diving in to the technical content of this overview, we need to build a basic understanding of retrieval augmented generation (RAG), how it works, and why it is useful. LLMs contain a lot of knowledge within their pretrained weights (i.e., parametric knowledge) that can be surfaced by prompting the model and generating output. However, these models also have a tendency to hallucinate—or generate false information—indicating that the parametric knowledge possessed by an LLM can be unreliable. Luckily, LLMs have the ability to perform in context learning (depicted above), defined as the ability to leverage information within the prompt to produce a better output1. With RAG, we augment the knowledge base of an LLM by inserting relevant context into the prompt and relying upon the in context learning abilities of LLMs to produce better output by using this context.

The Structure of a RAG Pipeline

“A RAG process takes a query and assesses if it relates to subjects defined in the paired knowledge base. If yes, it searches its knowledge base to extract information related to the user’s question. Any relevant context in the knowledge base is then passed to the LLM along with the original query, and an answer is produced.” - source

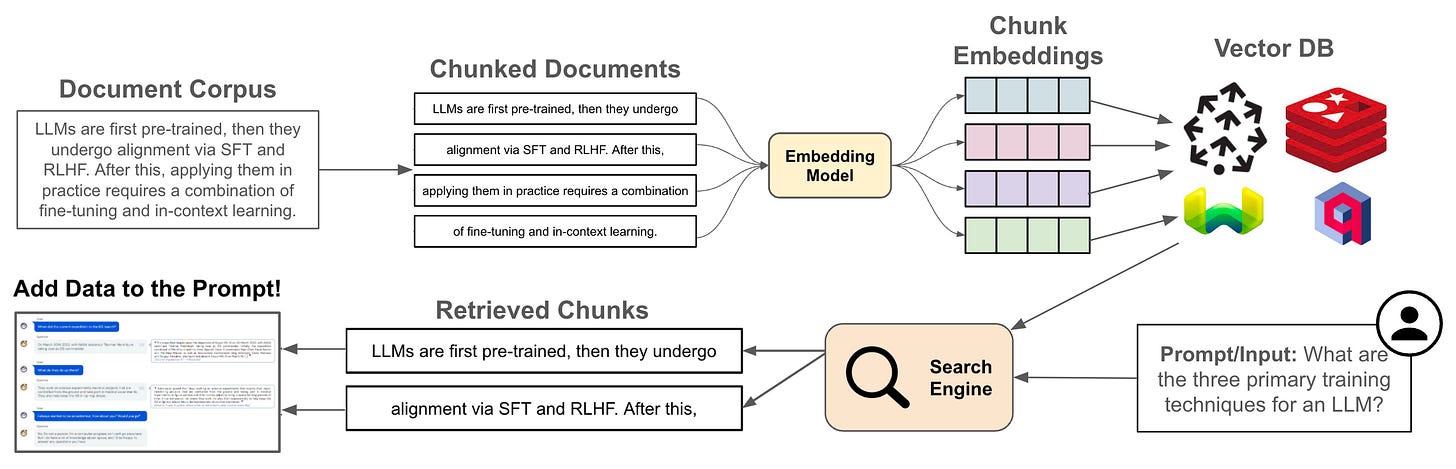

Given an input query, we normally respond to this query with an LLM by simply ingesting the query (possibly as part of a prompt template) and generating a response with the LLM. RAG modifies this approach by combining the LLM with a searchable knowledge base. In other words, we first use the input query to search for relevant information within an external dataset. Then, we add the info that we find to the model’s prompt when generating output, allowing the LLM to use this context (via its in context learning abilities) to generate a better and more factual response; see below. By combining the LLM with a non-parametric data source, we can feed the model correct, specific, and up-to-date information.

Cleaning and chunking. RAG requires access to a dataset of correct and useful information to augment the LLM’s knowledge base, and we must construct a pipeline that allows us to search for relevant data within this knowledge base. However, the external data sources that we use for RAG might contain data in a variety of different formats (e.g., pdf, markdown, and more). As such, we must first clean the data and extract the raw textual information from these heterogenous data sources. Once this is done, we can “chunk” the data, or split it into sets of shorter sequences that typically contain around 100-500 tokens; see below.

The goal of chunking is to split the data into units of retrieval (i.e., pieces of text that we can retrieve as search results). An entire document could be too large to serve as a unit of retrieval, so we must split this document into smaller chunks. The most common chunking strategy is a fixed-size approach, which breaks longer texts into shorter sequences that each contain a fixed number of tokens. However, this is not the only approach! Our data may be naturally divided into chunks (e.g., social media posts or product descriptions on an e-commerce store) or contain separators that allow us to use a variable-size chunking strategy.

Searching over chunks. Once we have cleaned our data and separated it into searchable chunks, we must build a search engine for matching input queries to chunks! Luckily, we have covered the topic of AI-powered search extensively in a prior overview. All of these concepts can be repurposed to build a search engine that can accurately match input queries to textual chunks in RAG.

First, we will want to build a dense retrieval system by i) using an embedding model2 to produce a corresponding vector representation for each of our chunks and ii) indexing all of these vector representations within a vector database. Then, we can embed the input query using the same embedding model and perform an efficient vector search to retrieve semantically-related chunks; see above.

Many RAG applications use pure vector search to find relevant textual chunks, but we can create a much better retrieval pipeline by re-purposing existing approaches from AI-powered search. Namely, we can augment dense retrieval with a lexical (or keyword-based) retrieval component, forming a hybrid search algorithm. Then, we can add a fine-grained re-ranking step—either with a cross-encoder or a less expensive component (e.g., ColBERT [10])—to sort candidate chunks based on relevance; see above for a depiction.

More data wrangling. After retrieval, we might perform additional data cleaning on each textual chunk to compress the data or emphasize key information. For example, some practitioners add an extra processing step after retrieval that passes textual chunks through an LLM for summarization or reformatting prior to feeding them to the final LLM—this approach is common in LangChain. Using this approach, we can pass a compressed version of the textual information into the LLM’s prompt instead of the full document, thus saving costs.

Do we always search for chunks? Within RAG, we usually use search algorithms to match input queries to relevant textual chunks. However, there are several different algorithms and tools that can be used to power RAG. For example, practitioners have recently explored connecting LLMs to graph databases, forming a RAG system that can search for relevant information via queries to a graph database (e.g., Neo4J); see here. Similarly, researchers have found synergies between LLMs and recommendation systems [14], as well as directly connected LLMs to search APIs like Google or Serper for accessing up-to-date information.

Generating the output. Once we have retrieved relevant textual chunks, the final step of RAG is to insert these chunks into a language model’s prompt and generate an output; see above. RAG comprises the full end-to-end process of ingesting an input query, finding relevant textual chunks, concatenating this context with the input query3, and using an LLM to generate an output based on the combined input. As we will see, such an approach has a variety of benefits.

The Benefits of RAG

“RAG systems are composed of a retrieval and an LLM based generation module, and provide LLMs with knowledge from a reference textual database, which enables them to act as a natural language layer between a user and textual databases, reducing the risk of hallucinations.” - from [8]

Implementing RAG allows us to specialize an LLM over a knowledge base of our choosing. Compared to other knowledge injection techniques—finetuning (or continued pretraining) is the primary alternative—RAG is both simpler to implement and computationally cheaper. As we will see, RAG also produces much better results compared to continued pretraining! However, implementing RAG still requires extra effort compared to just prompting a pretrained LLM, so we will briefly cover here the core benefits of RAG that make it worthwhile.

Reducing hallucinations. The primary reason that RAG is so commonly-used in practice is its ability to reduce hallucinations (i.e., generation of false information by the LLM). While LLMs tend to produce incorrect information when relying upon their parametric knowledge, the incorporation of RAG can drastically reduce the frequency of hallucinations, thus improving the overall quality of any LLM application and building more trust among users. Plus, RAG provides us with direct references to data that is used to generate information within the model’s output. We can easily provide the user with references to this information so that the LLM’s output can be verified against the actual data; see below.

Access to up-to-date information. When relying upon parametric knowledge, LLMs typically have a knowledge cutoff date. If we want to make this knowledge cutoff more recent, we would have to continually train the LLM over new data, which can be expensive. Plus, recent research has shown that finetuning tends to be ineffective at injecting new knowledge into an LLM—most information is learned during pretraining [7, 15]. With RAG, however, we can easily augment the LLM’s output and knowledge base with accurate and up-to-date information.

Data security. When we add data into an LLM’s training set, there is always a chance that the LLM will leak this data within its output. Recently, researchers have shown that LLMs are prone to data extraction attacks that can discover the contents of an LLM’s pretraining dataset via prompting techniques. As such, including proprietary data within an LLM’s training dataset is a security risk. However, we can still specialize an LLM to such data using RAG, which mitigates the security risk by never actually training the model over proprietary data.

“Retrieval-augmented generation gives models sources they can cite, like footnotes in a research paper, so users can check any claims. That builds trust.” - source

Ease of implementation. Finally, one of the biggest reasons to use RAG is the simple fact that the implementation is quite simple compared to alternatives like finetuning. The core ideas from the original RAG paper [1] can be implemented in only five lines of code, and there is no need to train the LLM itself. Rather, we can focus our finetuning efforts on improving the quality of the smaller, specialized models that are used for retrieval within RAG, which is much cheaper/easier.

From the Origins of RAG to Modern Usage

Many of the ideas used by RAG are derived from prior research on the topic of question answering. Interestingly, however, the original proposal of RAG in [1] was largely inspired (as revealed by the author of RAG) by a single paper [16] that augments the language model pretraining process with a similar retrieval mechanism. Namely, RAG was inspired by a “compelling vision of a trained system that had a retrieval index in the middle of it, so it could learn to generate any text output you wanted (source)”. Within this section, we will outline the origins of RAG and how this technique has evolved to be used in modern LLM applications.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks [1]

RAG was first proposed in [1]—in 2021, when LLMs were less explored and Seq2Seq models were extremely popular—to help with solving knowledge-intensive tasks, or tasks that humans cannot solve without access to an external knowledge source. As we know, pretrained language models possess a lot of information within their parameters, but they have a notoriously poor ability to access and manipulate this knowledge base4. For this reason, the performance of language model-based systems was far behind that of specialized, extraction-based methods at the time of RAG’s proposal. Put simply, researchers were struggling to find an efficient and simple method of expanding the knowledge base of a pretrained model.

“The retriever provides latent documents conditioned on the input, and the seq2seq model then conditions on these latent documents together with the input to generate the output.” - from [1]

How can RAG help? The idea behind RAG is to improve a pretrained language model’s ability to access and use knowledge by connecting it with a non-parametric memory store—typically a set of documents or textual data over which we can perform retrieval; see below. Using this approach, we can dynamically retrieve relevant information from our datastore when generating output with the model. Not only does this approach provide extra (factual) context to the model, but it also allows us (i.e., the people using/training the model) to examine the results of retrieval and gain more insight into the LLM’s problem-solving process. In comparison, the generations of a pretrained language model are largely a black box!

The pretrained model in [1] is actually finetuned using this RAG setup. As such, the RAG strategy proposed in [1] is not simply an inference-time technique for improving factuality. Rather, it is a general-purpose finetuning recipe that allows us to connect pretrained language models with external information sources.

Details on the setup. Formally, RAG considers an input sequence x (i.e., the prompt) and uses this input to retrieve documents z (i.e., the text chunks), which are used as context when generating a target sequence y. For retrieval, authors in [1] use the dense passage retrieval (DPR) model [2]5, a pretrained bi-encoder that uses separate BERT models to encode queries (i.e., query encoder) and documents (i.e., document encoder); see below. For generation, a pretrained BART model [3] is used. BART is an encoder-decoder (Seq2Seq) language model that is pretrained using a denoising objective6. Both the retriever and the generator in [1] are based upon pretrained models, which makes finetuning optional—the RAG setup already possesses the ability to retrieve and leverage knowledge via its pretrained components.

The data used for RAG in [1] is a Wikipedia dump that is chunked into sequences of 100 tokens. The chunk size used for RAG is a hyperparameter that must be tuned depending upon the application. Each chunk is converted to a vector embedding using DPR’s pretrained document encoder. Using these embeddings, we can build an index for efficient vector search and retrieve relevant chunks when given a sequence of text (e.g., a prompt or message) as input.

Training with RAG. The dataset used to train the RAG model in [1] contains pairs of input queries and desired responses. When training the model in [1], we first embed the input query using the query encoder of DPR and perform a nearest neighbor search within the document index to return the K most similar textual chunks. From here, we can concatenate a textual chunk with the input query and pass this concatenated input to BART to generate an output; see below.

The model in [1] only takes a single document as input when generating output with BART. As such, we must marginalize over the top K documents when generating text, meaning that we predict a distribution over generated text using each individual document. In other words, we run a forward pass of BART with each of the different documents used as input. Then, we take a weighted sum over the model’s outputs (i.e., each output is a probability distribution over generated text) based upon the probability of the document used as input. This document probability is derived from the retrieval score (e.g., cosine similarity) of the document. In [1], two methods of marginalizing over documents are proposed:

RAG-Sequence: the same document is used to predict each target token.

RAG-Token: each target token is predicted with a different document.

At inference time, we can generate an output sequence using either of these approaches using a modified form of beam search. To train the model, we simply use a standard language modeling objective that maximizes the log probability of the target output sequence. Notably, the RAG approach proposed in [1] only trains the DPR query encoder and the BART generator, leaving the document encoder fixed. This way, we can avoid having to constantly rebuild the vector search index used for retrieval, which would be expensive.

How does it perform? The RAG formulation proposed in [1] is evaluated across a wide variety of knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. On these datasets, the RAG formulation is compared to:

Extractive methods: operate by predicting an answer in the form of a span of text from a retrieved document.

Closed-book methods: operate by generating an answer to a question without any associated retrieval mechanism.

As shown in the tables above, RAG sets new state-of-the-art performance on open domain question answering tasks (left table), outperforming both extractive and Seq2Seq models. Interestingly, RAG even outperforms baselines that use a cross-encoder-style retriever for documents. Compared to extractive approaches, RAG is more flexible, as questions can still be answered even when they are not directly present within any of the retrieved documents.

“RAG combines the generation flexibility of the closed-book (parametric only) approaches and the performance of open-book retrieval-based approaches.” - from [1]

On abstractive question answering tests, RAG achieves near state-of-the-art performance. Unlike RAG, baseline techniques are given access to a gold passage that contains the answer to each question, and many questions are quite difficult to answer without access to this information (i.e., necessary information might not be present in Wikipedia). Despite this deficit, RAG tends to generate responses that are more specific, diverse, and factually grounded.

Using RAG in the Age of LLMs

Although RAG was originally proposed in [1], this strategy—with some minor differences—is still heavily used today to improve the factuality of modern LLMs. The structure of RAG used for LLMs is shown within the figure above. The main differences between this approach and that of [1] are the following:

Finetuning is optional and oftentimes not used. Instead, we rely upon the in context learning abilities of the LLM to leverage the retrieved data.

Due to the large context windows present in most LLMs, we can pass several documents into the model’s input at once when generating a response7.

Going further, the RAG approach in [1] uses purely vector search (with a bi-encoder) to retrieve document chunks. However, there is no reason that we have to use pure vector search! Put simply, the document retrieval mechanism used for RAG is just a search engine. So, we can apply everything we know about AI-powered search to craft the best RAG pipeline possible!

“Giving your LLM access to a database it can write to and search across is very useful, but it’s ultimately best conceptualized as giving an agent access to a search engine, versus actually having more memory.” - source

Within this section, we will go over more recent research that builds upon work in [1] and applies this RAG framework to modern, generative (decoder-only) LLMs. As we will see, RAG is highly impactful in this domain due to the emergent ability of LLMs to perform in context learning. Namely, we can inject knowledge into an LLM by just including relevant information in the prompt!

How Context Affects Language Models' Factual Predictions [4]. Pretrained LLMs have factual information encoded within their parameters, but there are limitations with leveraging this knowledge base—pretrained LLMs tend to struggle with storing and extracting (or manipulating) knowledge in a reliable fashion. Using RAG, we can mitigate these issues by injecting reliable and relevant knowledge directly into the model’s input. However, existing approaches—including work in [1]—use a supervised approach for RAG, where the model is directly trained to leverage this context. In [4], authors explore an unsupervised approach for RAG that leverages a pretrained retrieval mechanism and generator, finding that the benefit of RAG is still large when no finetuning is performed; see above.

“Supporting a web scale collection of potentially millions of changing APIs requires rethinking our approach to how we integrate tools.” - from [5]

Gorilla: Large Language Models Connected with Massive APIs [5]. Combining language models with external tools is a popular topic in AI research. However, these techniques usually teach the underlying LLM to leverage a small, fixed set of potential tools (e.g., a calculator or search engine) to solve problems. In contrast, authors in [5] develop a retrieval-based finetuning strategy to train an LLM, called Gorilla, to use over 1,600 different deep learning model APIs (e.g., from HuggingFace or TensorFlow Hub) for problem solving; see below.

First, the documentation for all of these different deep learning model APIs is downloaded. Then, a self-instruct [6] approach is used to generate a finetuning dataset that pairs questions with an associated response that leverages a call to one of the relevant APIs. From here, the model is finetuned over this dataset in a retrieval-aware manner, in which a pretrained information retrieval system is used to retrieve the documentation of the most relevant APIs for solving each question. This documentation is then passed into the model’s prompt when generating output, thus teaching the model to leverage the documentation of retrieved APIs when solving a problem and generating API calls; see below.

Unlike most RAG applications, Gorilla is actually finetuned to better leverage its retrieval mechanism. Interestingly, such an approach allows the model to adapt to real-time changes in an API’s documentation at inference time and even enables the model to generate fewer hallucinations by leveraging relevant documentation.

Fine-Tuning or Retrieval? Comparing Knowledge Injection in LLMs [7]. In [7], authors study the concept of knowledge injection, which refers to methods of incorporating information from an external dataset into an LLM’s knowledge base. Given a pretrained LLM, the two basic ways that we can inject knowledge into this model are i) finetuning (i.e., continued pretraining) and ii) RAG.

We see in [4] that RAG far outperforms finetuning with respect to injecting new sources of information into an LLM’s responses; see below. Interestingly, combining finetuning with RAG does not consistently outperform RAG alone, thus revealing the impact of RAG on the LLM’s factuality and response quality.

RAGAS: Automated Evaluation of Retrieval Augmented Generation [8]. RAG is an effective tool for LLM applications. However, the approach is difficult to evaluate, as there are many dimensions of “performance” that characterize an effective RAG pipeline:

The ability to identify relevant documents.

Properly exploiting data in the documents via in context learning.

Generating a high-quality, grounded output.

RAG is not just a retrieval system, but rather a multi-step process of finding useful information and leveraging this information to generate better output with LLMs. In [8], authors propose an approach, called Retrieval Augmented Generation Assessment (RAGAS), for evaluating these complex RAG pipelines without any human-annotated datasets or reference answers. In particular, three classes of metrics are used for evaluation:

Faithfulness: the answer is grounded in the given context.

Answer relevance: the answer addresses the provided question.

Context relevance: the retrieved context is focused and contains as little irrelevant information as possible.

Together, these metrics—as claimed by authors in [8]—holistically characterize the performance of any RAG pipeline. Additionally, we can evaluate each of these metrics in an automated fashion by prompting powerful foundation models like ChatGPT or GPT-4. For example, faithfulness is evaluated in [8] by prompting an LLM to extract a set of factual statements from the generated answer, then prompting an LLM again to determine if each of these statements can be inferred from the provided context; see below. Answer and context relevance are evaluated similarly (potentially with some added tricks based on embedding similarity8).

Notably, the RAGAS toolset is not just a paper. These tools, which are now quite popular among LLM practitioners, have been implemented and openly released online. The documentation of RAGAS tools is provided at the link below.

Practical Tips for RAG Applications

Although a variety of papers have been published on the topic of RAG, this technique is most popular among practitioners. As a result, many of the best takeaways for how to successfully use RAG are hidden within blog posts, discussion forums, and other non-academic publications. Within this section, we will capture some of this domain knowledge by outlining the most important practical lessons of which one should be aware when building a RAG application.

RAG is a Search Engine!

When applying RAG in practical applications, we should realize that the retrieval pipeline used for RAG is just a search engine! Namely, the same retrieval and ranking techniques that have been used by search engines for years can be applied by RAG to find more relevant textual chunks. From this realization, there are several practical tips that can be derived for improving RAG.

Don’t just use vector search. Many RAG systems purely leverage dense retrieval for finding relevant textual chunks. Such an approach is quite simple, as we can just i) generate an embedding for the input prompt and ii) search for related chunks in our vector database. However, semantic search has a tendency to yield false positives and may have noisy results. To solve this, we should perform hybrid retrieval using a combination of vector and lexical search—just like a normal (AI-powered) search engine! The approach to vector search does not change, but we can perform a parallel lexical search by:

Extracting keywords from the input prompt9.

Performing a lexical search with these keywords.

Taking a weighted combination of results from lexical/vector search.

By performing hybrid search, we make our RAG pipeline more robust and reduce the frequency of irrelevant chunks in the model’s context. Plus, adopting keyword-based search allows us to perform clever tricks like promoting documents with important keywords, excluding documents with negative keywords, or even augmenting documents with synthetically-generated data for better matching!

Optimizing the RAG pipeline. To improve our retrieval system, we need to collect metrics that allow us to evaluate its results similarly to any normal search engine. One way this can be done is by displaying the textual chunks used for certain generations to the end user similarly to a citation, such that the user can use the information retrieved by RAG to verify the factual correctness of the model’s output. As part of this system, we could then prompt the user to provide binary feedback (i.e., thumbs up or thumbs down) as to whether the information was actually relevant; see below. Using this feedback, we can evaluate the results of our retrieval system using traditional search metrics (e.g., DGC or nDCG), test changes to the system via AB tests, and iteratively improve our results.

Evaluations for RAG must go beyond simply verifying the results of retrieval. Even if we retrieve the perfect set of context to include within the model’s prompt, the generated output may still be incorrect. To evaluate the generation component of RAG, the AI community relies heavily upon automated metrics such as RAGAS [8] or LLM as a Judge [9]10, which perform evaluations by prompting LLMs like GPT-4; see here for more details. These techniques seem to provide reliable feedback on the quality of generated output. To successfully apply RAG in practice, however, it is important that we evaluate all parts of the end-to-end RAG system—including both retrieval and generation—so that we can reliably benchmark improvements that are made to each component.

Improving over time. Once we have built a proper retrieval pipeline and can evaluate the end-to-end RAG system, the last step of applying RAG is to perform iterative improvements using a combination of better models and data. There are a variety of improvements that can be investigated, including (but not limited to):

Adding ranking to the retrieval pipeline, either using a cross-encoder or a hybrid model that performs both retrieval and ranking (e.g., ColBERT [10]).

Finetuning the embedding model for dense retrieval over human-collected relevance data (i.e., pairs of input prompts with relevant/irrelevant passages).

Finetuning the LLM generator over examples of high-quality outputs so that it learns to better follow instructions and leverage useful context.

Using LLMs to augment either the input prompt or the textual chunks with extra synthetic data to improve retrieval.

For each of these changes, we can measure their impact over historical data in an offline manner. To truly understand whether they positively impact the RAG system, however, we should rely upon online AB tests that compare metrics from the new and improved system to the prior system in real-time tests with humans.

Optimizing the Context Window

Successfully applying RAG is not just a matter of retrieving the correct context—prompt engineering plays a massive role. Once we have the relevant data, we must craft a prompt that i) includes this context and ii) formats it in a way that elicits a grounded output from the LLM. Within this section, we will investigate a few strategies for crafting effective prompts with RAG to gain a better understanding of how to properly include context within a model’s prompt.

RAG needs a larger context window. During pretraining, an LLM sees input sequences of a particular length. This choice of sequence length during pretraining becomes the model’s context length. Recently, we have seen a trend in AI research towards the creation of LLMs with longer context lengths11. See, for example, MPT-StoryWriter-65K, Claude-2.1, or GPT-4-Turbo, which have context lengths of 65K, 200K, and 128K, respectively. For reference, the Great Gatsby (i.e., an entire book!) only contains ~70K tokens. Although not all LLMs have a large context window, RAG requires a model with a large context window so that we can include a sufficient number of textual chunks in the model’s prompt.

Maximizing diversity. Once we’ve been sure to select an LLM with a sufficiently large context length, the next step in applying RAG is to determine how to select the best context to include in the prompt. Although the textual chunks to be included are selected by our retrieval pipeline, we can optimize our prompting strategy by adding a specialized selection component12 that sub-selects the results of retrieval. Selection does not change the retrieval process of RAG. Rather, selection is added to the end of the retrieval pipeline—after relevant chunks of text have already been identified and ranked—to determine how documents can best be sub-selected and ordered within the resulting prompt.

One popular selection approach is a diversity ranker, which can be used to maximize the diversity of textual chunks included in the model’s prompt by performing the following steps:

Use the retrieval pipeline to generate a large set of documents that could be included in the model’s prompt.

Select the document that is most similar to the input (or query), as determined by embedding cosine similarity.

For each remaining document, select the document that is least similar to the documents that are already selected13.

Notably, this strategy solely optimizes for the diversity of selected context, so it is important that we apply this selection strategy after a set of relevant documents has been identified by the retrieval pipeline. Otherwise, the diversity ranker would select diverse, but irrelevant, textual chunks to include in the context.

Optimizing context layout. Despite increases in context lengths, recent research indicates that LLMs struggle to capture information in the middle of a large context window [11]. Information at the beginning and end of the context window is captured most accurately, causing certain data to be “lost in the middle”. To solve this issue, we can adopt a selection strategy that is more mindful of where context is placed in the prompt. In particular, we can take the relevant textual chunks from our retrieval pipeline and iteratively place the most relevant chunks at the beginning and end of the context window; see below. Such an approach avoids inserting textual chunks in order of relevance, choosing instead to place the most relevant chunks at the beginning and end of the prompt.

Data Cleaning and Formatting

In most RAG applications, our model will be retrieving textual information from many different sources. For example, an assistant that is built to discuss the details of a codebase with a programmer may pull information from the code itself, documentation pages, blog posts, user discussion threads, and more. In this case, the data being used for RAG has a variety of different formats that could lead to artifacts (e.g., logos, icons, special symbols, and code blocks) within the text that have the potential to confuse the LLM when generating output. In order for the application to function properly, we must extract, clean, and format the text from each of these heterogenous sources. Put simply, there’s a lot more to preprocessing data for RAG than just splitting textual data into chunks!

Performance impact. If text is not extracted properly from each knowledge source, the performance of our RAG application will noticeably deteriorate! On the flip side, cleaning and formatting data in a standardized manner will noticeably improve performance. As shown in this blog post, investing into proper data preprocessing for RAG has several benefits (see above):

20% boost in the correctness of LLM-generated answers.

64% reduction in the number of tokens passed into the model14.

Noticeable improvement in overall LLM behavior.

“We wrote a quick workflow that leveraged LLM-as-judge and iteratively figured out the cleanup code to remove extraneous formatting tokens from Markdown files and webpages.” - from [12]

Data cleaning pipeline. The details of any data cleaning pipeline for RAG will depend heavily upon our application and data. To craft a functioning data pipeline, we should i) observe large amounts of data within our knowledge base, ii) visually inspect whether unwanted artifacts are present, and iii) amend issues that we find by adding changes to the data cleaning pipeline. Although this approach isn’t flashy or cool, any AI/ML practitioner knows that 90% of time building an application will be spent observing and working with data.

If we aren’t interested in manually inspecting data and want a sexier approach, we can automate the process of creating a functional data preprocessing pipeline by using LLM-as-a-Judge [9] to iteratively construct the code for cleaning up and properly formatting data. Such an approach was recently shown to retain useful information, remove formatting errors, and drastically reduce the average size of documents [12]. See here for the resulting data preprocessing script and below for an example of a reformatted document after cleanup.

Further Practical Resources for RAG

As previously mentioned, some of the best resources for learning about RAG are not published within academic journals or conferences. There are a variety of blog posts and practical write ups that have helped me to gain insight for how to better leverage RAG. Some of the most notable resources are outlined below.

What is Retrieval Augmented Generation? [link]

Building RAG-based LLM Applications for Production [link]

Best Practices for LLM Evaluation of RAG Applications [link]

Building Conversational Search with RAG at Vespa [link]

RAG Finetuning with Ray and HuggingFace [link]

Closing Thoughts

At this point, we should have a comprehensive grasp of RAG, its inner workings, and how we can best approach building a high-performing LLM application using RAG. Both the concept and implementation of RAG are simple, which—when combined with its impressive performance—is what makes the technique so popular among practitioners. However, successfully applying RAG in practice involves more than putting together a minimal functioning pipeline with pretrained components. Namely, we must refine our RAG approach by:

Creating a high-performing hybrid retrieval algorithm (potentially with a re-ranking component) that can accurately identify relevant textual chunks.

Constructing a functional data preprocessing pipeline that properly formats data and removes harmful artifacts before the data is used for RAG.

Finding the correct prompting strategy that allows the LLM to reliably incorporate useful context when generating output.

Putting detailed evaluations in place for both the retrieval pipeline (i.e., using traditional search metrics) and the generation component (using RAGAS or LLM-as-a-judge [8, 9]).

Collecting data over time that can be used to improve the RAG pipeline’s ability to discover relevant context and generate useful output.

Going further, creating a robust evaluation suite allows us to improve each of the components listed above by quantitatively testing (via offline metrics or an AB test) iterative improvements to our RAG pipeline, such as a modified retrieval algorithm or a finetuned component of the system. As such, our approach to RAG should mature (and improve!) over time as we test and discover new ideas.

New to the newsletter?

Hi! I’m Cameron R. Wolfe, deep learning Ph.D. and Director of AI at Rebuy. This is the Deep (Learning) Focus newsletter, where I help readers understand AI research via overviews of relevant topics from the ground up. If you like the newsletter, please subscribe, share it, or follow me on Medium, X, and LinkedIn!

Bibliography

[1] Lewis, Patrick, et al. "Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 9459-9474.

[2] Karpukhin, Vladimir, et al. "Dense passage retrieval for open-domain question answering." arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.04906 (2020).

[3] Lewis, Mike, et al. "Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension." arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.13461 (2019).

[4] Petroni, Fabio, et al. "How context affects language models' factual predictions." arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.04611 (2020).

[5] Patil, Shishir G., et al. "Gorilla: Large language model connected with massive apis." arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.15334 (2023).

[6] Wang, Yizhong, et al. "Self-instruct: Aligning language model with self generated instructions." arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10560 (2022).

[7] Ovadia, Oded, et al. "Fine-tuning or retrieval? comparing knowledge injection in llms." arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.05934 (2023).

[8] Es, Shahul, et al. "Ragas: Automated evaluation of retrieval augmented generation." arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.15217 (2023).

[9] Zheng, Lianmin, et al. "Judging LLM-as-a-judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena." arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05685 (2023).

[10] Khattab, Omar, and Matei Zaharia. "Colbert: Efficient and effective passage search via contextualized late interaction over bert." Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in Information Retrieval. 2020.

[11] Liu, Nelson F., et al. "Lost in the middle: How language models use long contexts." arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.03172 (2023).

[12] Leng, Quinn, el al. “Announcing MLflow 2.8 LLM-as-a-judge metrics and Best Practices for LLM Evaluation of RAG Applications, Part 2.” https://www.databricks.com/blog/announcing-mlflow-28-llm-judge-metrics-and-best-practices-llm-evaluation-rag-applications-part (2023).

[13] Brown, Tom, et al. "Language models are few-shot learners." Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 1877-1901.

[14] Wang, Yan, et al. "Enhancing recommender systems with large language model reasoning graphs." arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.10835 (2023).

[15] Zhou, Chunting, et al. "Lima: Less is more for alignment." arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11206 (2023).

[16] Guu, Kelvin, et al. "Retrieval augmented language model pre-training." International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020.

[17] Glaese, Amelia, et al. "Improving alignment of dialogue agents via targeted human judgements." arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14375 (2022).

Interestingly, in context learning is an emergent capability of LLMs, meaning that it is most noticeable in larger models. In context learning ability was first demonstrated by the impressive few-shot learning capabilities of GPT-3 [13].

We can also explore other ways of adding context to the query, such as by creating a more generic prompt template.

For more information, check out recent research on the reversal curse and knowledge manipulation within LLMs. These models oftentimes struggle to perform even simple manipulations (e.g., reversal) of factual relationships within their knowledge base.

The original RAG paper purely uses vector search (with a bi-encoder) to retrieve relevant documents.

The denoising objective used by BART considers several perturbations to the original sequence of text, such as token masking/deletion, masking entire sequences of tokens, permuting sentences in a document, or even rotating a sequence about a chosen token. Given the permuted input, the BART model is trained to reconstruct the original sequence of text during pretraining.

The number of textual chunks that we actually pass into the model’s prompt is dependent upon several factors, such as i) the model’s context window, ii) the chunk size, and iii) the application we are solving.

Context relevance follows a simple approach of prompting an LLM to determine whether sentences from the retrieved context are actually relevant or not. For answer relevance, however, we prompt an LLM to generate potential questions associated with the generated answer, then we take the average cosine similarity between the embeddings of these questions and the actual question as the final score.

This can be done via traditional query understanding techniques, or we can simply prompt an LLM to generate a list of keyword associated with the input.

LLMs can effectively evaluate unstructured outputs (semi-)reliably and at a low cost. However, human feedback remains the gold standard for evaluating an LLM’s output.

Plus, there has been a ton of research on extending the context length of existing, pretrained LLMs or making them more capable of handling longer inputs; e.g., ALiBi, RoPE, Self Extend, LongLoRA, and more.

Here, I call this step “selection” rather than ranking as to avoid confusion with re-ranking within search, which sorts documents based on textual relevance. Selection refers to the process of deciding the order of documents as they are inserted into the model’s prompt, and textual relevance is assumed to already be known at this step.

This is a greedy approach for selecting the most diverse subset of documents. The resulting set is not optimal in terms of diversity, but this efficient approximation does a good job of constructing a diverse set of documents in practice.

The cost reduction is due to a reduction in the average size of textual chunks after artifacts and unnecessary components are removed from the text.

Such a great write-up. The more accessible RAG is, the more widespread the adoption of LLMs becomes. For example, chunking and preprocessing, which remain manual steps that many aren't experienced with, can be semi-automated based on the task at hand. A superior chunking method can lead to a double-digit increase in performance.

Thank you so much for this deep dive, very informative! I'm a UX researcher that's new to conversational AI design (no ML practitioner, so please bare with me!) and for our LLM-powered voice assistant and chatbot, RAG has obviously become immensely important. I was wondering, when it comes to preprocessing data and curating a knowledge base for RAG, do the data for the external knowledge base need to be formatted/"cleaned" in a specific way? For example, is it sufficient to simply use links to a website and embedded PDFs/documents are then automatically included in the knowledge base, or would one need to extract and separately add the contents of the PDFs/documents to the database?