AI Agents from First Principles

Understanding AI agents by building upon the most basic concepts of LLMs...

The capabilities of large language models (LLMs) are advancing rapidly. As LLMs become more capable, we can use them to create higher-level systems that solve increasingly complex problems, interact with external environments and operate over longer time horizons—these are referred to as AI agent systems. AI agents are a popular topic, but there is considerable confusion regarding the definition and capabilities of these agents. In this overview, we will build an understanding of AI agents from first principles. Starting with a standard text-to-text LLM, we will explore how functionalities like tool usage, reasoning and more can enhance a standard LLM, leading to the creation of complex, autonomous systems.

LLMs and their Capabilities

The functionality of an LLM is depicted above. Given a textual prompt, the LLM generates a textual response. This functionality is easy to understand and can be generalized to solve nearly any problem. In many ways, the generality of an LLM is one of its biggest strengths. In this section, we will outline how new capabilities—such as reasoning or interacting with external APIs—can be integrated into an LLM by taking advantage of this text-to-text structure. As we will soon learn, advanced capabilities of modern AI agents are largely built upon this basic functionality.

Tool Usage

As LLMs started to become more capable, teaching them how to integrate with and use external tools quickly became a popular topic in AI research. Examples of useful tools that can be integrated with an LLM include calculators, calendars, search engines, code interpreters and more. Why is this approach so popular? Put simply, LLMs are (obviously) not the best tool for solving all tasks. In many cases, simpler and more reliable tools are available; e.g., calculators for performing basic arithmetic or search engines for getting up-to-date factual info on a certain topic. Given that LLMs excel in planning and orchestration, however, we can easily teach them how to use these tools as part of their problem solving process!

The fundamental idea behind tool-use LLMs is endowing an LLM with the ability to delegate sub-tasks or components of a problem to a more specialized or robust tool. The LLM serves as the “brain” that orchestrates various specialized tools together.

Finetuning for tool usage. Early work on tool use—e.g., LaMDA [2] or the Toolformer [3] (depicted above)—used targeted finetuning to teach an LLM how to leverage a fixed set of tools. We simply curate training examples where a function call to some tool is directly inserted into the LLM’s token stream; see below.

During training, these tool calls are treated similarly to any other token—they are just part of the textual sequence! When a call to a tool is generated by the LLM at inference time, we handle it as follows:

Stop generating tokens.

Parse the tool call (i.e., determine the tool being used and its parameters).

Make a call to the tool with these parameters.

Add the response from the tool to the LLM’s token stream.

Continue generating tokens.

The tool call can be handled in real-time as the LLM generates its output, and the information returned by the tool is added directly into the model’s context!

Prompt-based tool usage. Teaching LLMs to call tools via finetuning requires curating—usually with human annotation—a large training dataset. As LLM capabilities improved, later work instead emphasized in-context learning-based approaches for tool usage. Why would we finetune a language model when we can simply explain the tools that are available in the model’s prompt?

Prompt-based tool usage requires less human effort, allowing us to drastically increase the number of tools to which LLMs have access. For example, later work in this space integrates LLMs with hundreds [4] or even thousands [5] of tools; see above. To do this, we treat each tool as a generic API and provide the schema for relevant APIs as context in the model’s prompt. This approach enables LLMs to be integrated with arbitrary APIs on the internet using a standardized structure, which makes countless applications possible; e.g., finding information, calling other ML models, booking a vacation, handling your calendar and much more.

“Today, we're open-sourcing the Model Context Protocol (MCP), a new standard for connecting AI assistants to the systems where data lives, including content repositories, business tools, and development environments. Its aim is to help frontier models produce better, more relevant responses.” - from [15]

Model context protocol (MCP)—proposed by Anthropic—is a popular framework that extends upon the idea of allowing LLMs to interact with arbitrary tools. Put simply, MCP standardizes the format used by external systems to provide context into the prompt of an LLM. To solve complex problems, LLMs will need to integrate with a progressively larger set of external tools over time. To streamline this process, MCP proposes a standard format for these integrations and allows developers to create pre-built integrations, called MCP servers, that can be used by any LLM to connect with a variety of custom data sources; see below.

For those who are interested in digging deeper into tool usage, please see the following series of overview on this topic:

Finetuning LLMs to use tools [link]

Prompt-based tool usage [link]

Integrating LLMs with code interpreters [link]

Allowing LLMs to create their own tools [link]

Limitations of tool usage. Despite the power of the tool usage paradigm, the capabilities of tool-use LLMs are limited by their reasoning capabilities. To effectively leverage tools, our LLM must be able to:

Decompose complex problems into smaller sub-tasks.

Determine what tools should be used to solve a problem.

Reliably craft calls to relevant tools with the correct format.

Complex tool usage requires the LLM to be an effective orchestrator, which is very dependent upon the model’s reasoning capabilities and overall reliability.

Reasoning Models

Given the relationship between agency and reasoning, reasoning capabilities have been a core focus of LLM research for several years. For a more in-depth overview of current reasoning research, please see the overview below. However, we will briefly cover the key ideas behind reasoning models here for completeness.

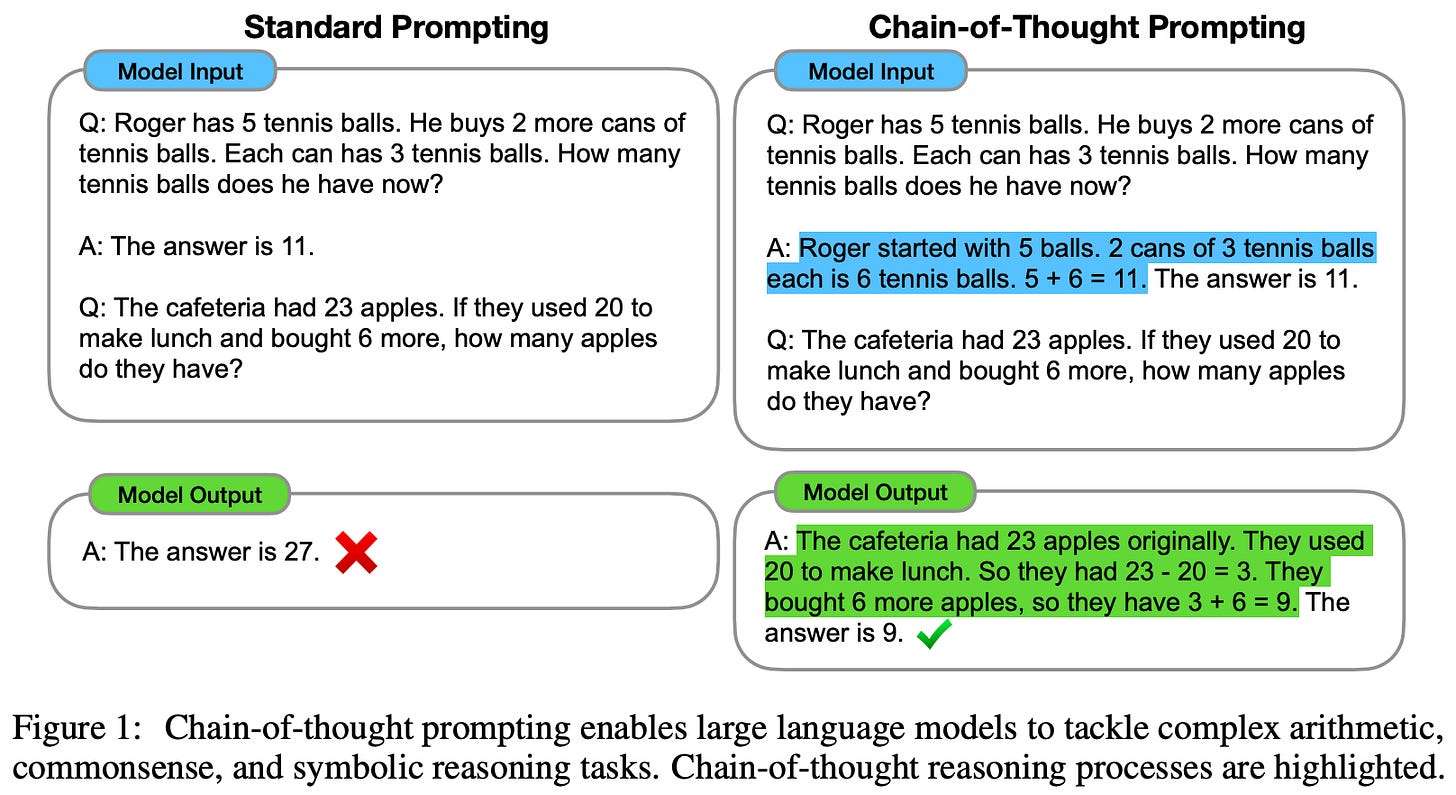

CoT prompting. When LLMs first became popular, one of the most common criticisms of these models was that they could not perform complex reasoning. However, research on Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting [6, 7] revealed that vanilla LLMs are better at reasoning than we initially realized. The idea behind CoT prompting is simple. Instead of directly prompting an LLM for output, we ask it to generate a rationale or explanation prior to its final output; see below.

Interestingly, this approach drastically improves the performance of vanilla LLMs on reasoning tasks, indicating that LLMs are capable of complex reasoning—to a reasonable extent—if we can find the correct approach to elicit these capabilities.

Reasoning models. CoT prompting is incredibly effective and is a core part of all modern LLMs; e.g., ChatGPT usually outputs a CoT with its answers by default. However, this approach to reasoning is also somewhat naive. The entire reasoning process revolves around the CoT generated by the LLM and there is no dynamic adaptation based on the complexity of the problem being solved.

To solve these issues, recent research has introduced new training strategies to create LLMs that specialize in reasoning (i.e., reasoning models). These models approach problem solving differently compared to standard LLMs—they spend a variable amount of time “thinking” prior to providing an answer to a question.

The thoughts of a reasoning model are just standard chains of thought, but a CoT from a reasoning model is much longer than that of a standard LLM (i.e., can be several thousands of tokens), tends to exhibit complex reasoning behavior (e.g., backtracking and self-refinement) and can dynamically adapt based on the difficulty of the problem being solved—harder problems warrant a longer CoT.

The key advancement that made reasoning models possible was large-scale post-training with reinforcement learning from verifiable rewards (RLVR); see above. If we have a dataset of ground truth solutions to verifiable problems (e.g., Math or coding), we can simply check whether the answer generated by the LLM is correct and use this signal to train a model with RL. During this training process, reasoning models naturally learn how to generate long chains of thought to solve verifiable reasoning problems via RL-powered self-evolution.

“We explore the potential of LLMs to develop reasoning capabilities without any supervised data, focusing on their self-evolution through a pure reinforcement learning process.” - from [8]

Reasoning trajectories. In summary, reasoning models, which are trained via large-scale post-training with RLVR, change the behavior of a standard LLM as shown below. Instead of directly generating output, the reasoning model first generates an arbitrarily long CoT1 that decomposes and solves the reasoning task—this is the “thinking” process. We can change how much the model thinks by controlling the length of this reasoning trace; e.g., the o-series of reasoning models from OpenAI provide low, medium and high levels of reasoning effort.

Although the model still generates a single output given a prompt, the reasoning trajectory implicitly demonstrates a variety of advanced behaviors; e.g., planning, backtracking, monitoring, evaluation and more. For examples of these reasoning trajectories and their properties, see the Synthetic-1 dataset, which contains over 2M examples of reasoning traces generated by DeepSeek-R1.

Reasoning + agents. Given recent advancements in reasoning, a sufficiently capable LLM that can plan and effectively reason over its instructions should be able to decompose a problem, solve each component of the problem and arrive at a final solution itself. Providing LLMs with more autonomy and relying on their capabilities—rather than human intervention—to solve complex problems is a key idea behind agent systems. To make the idea of an agent more clear, let’s now discuss a framework that can be used to design these types of systems.

The ReAct Framework [1]

“It is becoming more evident that with the help of LLMs, language as a fundamental cognitive mechanism will play a critical role in interaction and decision making.” - from [1]

ReAct [1]—short for REasoning and ACTion—is one of the first general frameworks to be proposed for autonomously decomposing and solving complex problems with an LLM agent. We can think of ReAct as a sequential, multi-step problem-solving process powered by an LLM at its core. At each time step t, the LLM incorporates any feedback that is available and considers the current state of the problem it is trying to solve, allowing it to effectively reason over and select the best possible course of action for the future. Given that (nearly) any LLM system can be modeled sequentially, ReAct is a generic and powerful framework.

Creating a Framework for Agents

At a particular time step t, our agent is given an observation from its environment o_t. Based upon this observation, our agent will decide to take some action a_t, which may be intermediate—such as searching the web to find data that is needed to solve a problem—or terminal (i.e., the final action that “solves” the problem of interest). We define the function that our agent uses to produce this action as a policy π2. The policy takes the context—a concatenated list of prior actions and observations from the agent—as input and predicts the next action a_t as output, either deterministically or stochastically3. As depicted below, this loop of observations and actions continues until our agent outputs a terminal action.

ReAct [1] makes one key modification to the observation-action loop shown above. The space of potential actions that can be outputted by the policy A typically includes the set of intermediate and terminal actions that can be taken by the agent; e.g., searching for data on the web or outputting a final solution to a problem. However, ReAct expands the action space to include language, allowing the agent to produce a textual output as an action instead of taking a traditional action. In other words, the agent can choose to “think”; see below.

Formally, we can define a thought as a special kind of action as shown above. As one might infer from the name of the framework, the primary motivation behind ReAct is finding a balance between reasoning and action. Similarly to a human, the agent should be able to think and plan the actions that it takes in an environment—reasoning and action have a symbiotic relationship.

“Reasoning traces help the model induce, track, and update action plans, while actions allow it to interface with and gather additional information from external sources such as knowledge bases or environments.” - from [1]

How do agents think?

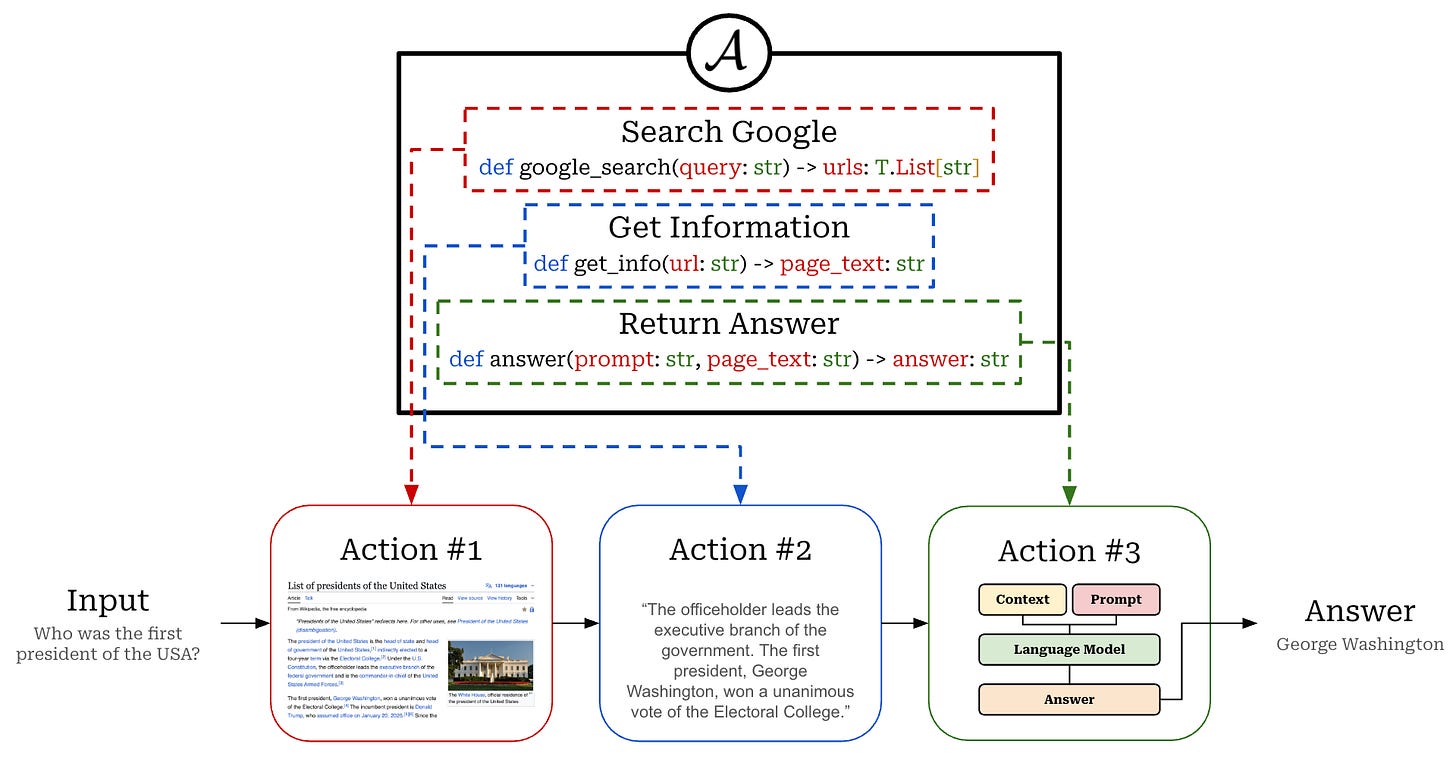

The traditional action space for an agent is discrete and—in most cases—relatively small. For example, an agent specialized in question-answering could have the following options for actions (depicted above):

Perform a Google search to retrieve relevant webpages.

Grab relevant information from a particular webpage.

Return a final answer.

There are only so many actions that this agent can take while working towards a solution. In contrast, the space of language is virtually unlimited. As a result, the ReAct framework requires the use of a strong language model as its policy. In order to produce useful thoughts that benefit performance, the LLM backend of our agent system must possess advanced reasoning and planning capabilities!

“Learning in this augmented action space is difficult and requires strong language priors… we mainly focus on the setup where a frozen large language model… is prompted with few-shot in-context examples to generate both domain-specific actions and free-form language thoughts for task solving.” - from [1]

Thought patterns. Common examples of useful thought patterns that can be produced by an agent include decomposing tasks, creating itemized action plans, tracking progress toward a final solution, or simply outputting information—from the implicit knowledge base of the LLM—that may be relevant to solving a problem.

Agents use their thinking ability to explicitly describe how a problem should be solved and then execute—and monitor the execution of—this plan. In both of the examples above, the agent explicitly writes out the next steps that it needs to perform when solving a problem; e.g., “Next, I need to…” or “I need to search…”.

In most cases, the thoughts produced by an agent—commonly referred to as a problem or task-solving trajectory—mimic that of a human trying to solve a problem. In fact, experiments with ReAct in [1] guide the agent’s approach to a problem by providing in-context examples of task-solving trajectories (i.e., actions, thoughts and observations) used by humans to solve similar problems. Agents prompted in this fashion are likely adopt a human-like reasoning process.

“We let the language model decide the asynchronous occurrence of thoughts and actions for itself.” - from [1]

When should the agent think? Depending on the problem we are solving, the ReAct framework can be setup differently. For reasoning heavy tasks, thoughts are typically interleaved with actions—we can hard-code the agent such that it produces a single thought before every action. However, the agent can also be given the ability to determine for itself whether thinking is necessary. For tasks that require a lot of actions (i.e., decision-making tasks), the agent may choose to use thoughts more sparsely within its problem-solving trajectory.

Concrete Use Cases

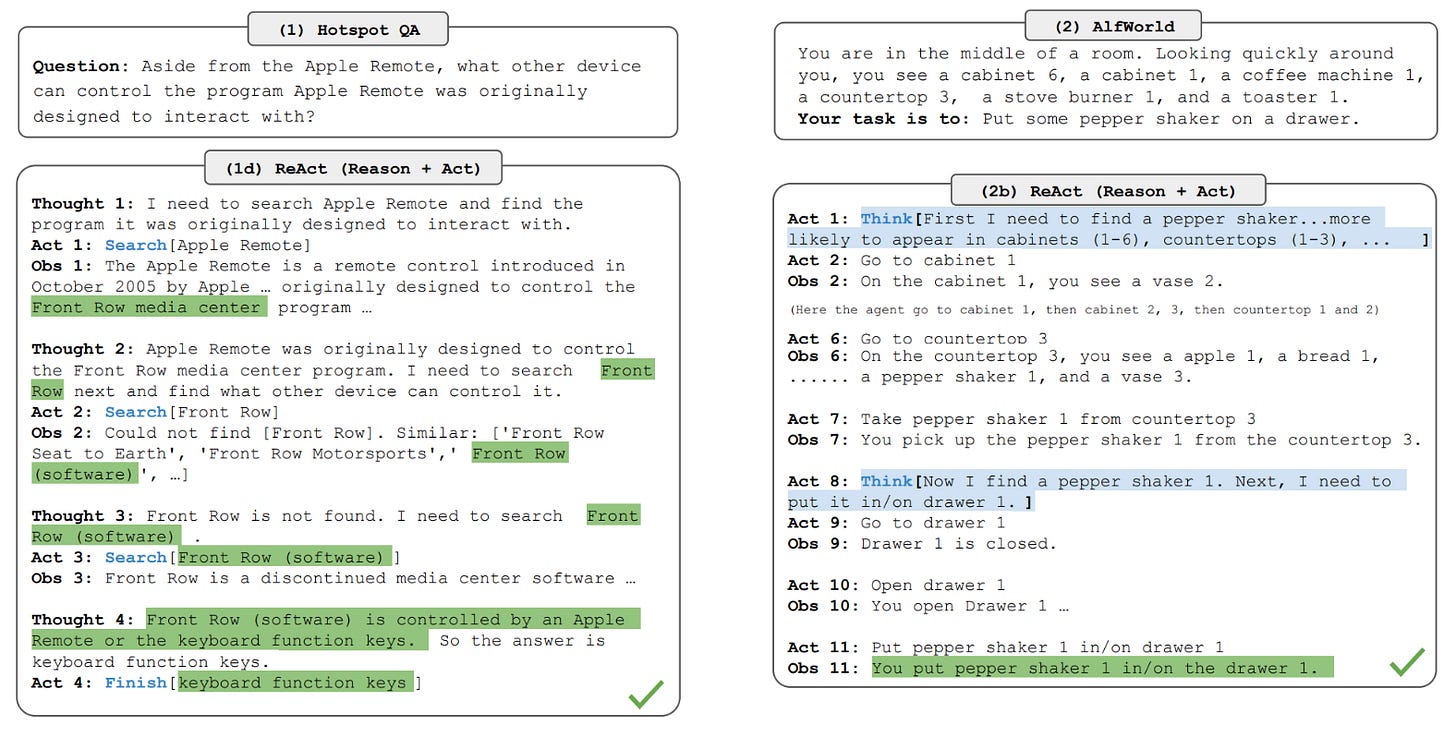

Two use cases are considered for applications of the ReAct framework in [1]:

Knowledge-intensive reasoning: using ReAct for question answering and fact verification tasks (e.g., HotpotQA and FEVER).

Decision making: applying ReAct to interactive (language-based) decision-making tasks; e.g., ALFWorld for navigating simulated households or WebShop for completing autonomous shopping tasks.

Examples of ReAct being applied in each use case are provided above. The ReAct framework is implemented with an LLM—PaLM-540B in particular—that is prompted with several in-context examples that outline the problem solving process. The LLM’s prompt provides human-crafted thought-action-observation trajectories that are followed to arrive at a final solution to a question.

“By interacting with a Wikipedia API, ReAct is able to retrieve information to support reasoning, while also use reasoning to target what to retrieve next, demonstrating a synergy of reasoning and acting.” - from [1]

Knowledge-intensive reasoning. In this domain, the LLM agent is provided only a question (and optionally a claim) as input. To answer a question or evaluate the correctness of a claim, the LLM must either rely upon its internal knowledge base or retrieve necessary information from an external environment. Specifically, the agent’s action space is outlined below. Here, we see that authors in [1] expose basic information retrieval functionality—reflective of how a typical human would lookup information on Wikipedia—to the LLM agent via its action space.

To teach the LLM how to properly think and act in this environment, humans manually craft ReAct-style problem-solving trajectories for each application dataset, including six trajectories for HotpotQA and three trajectories for FEVER. These trajectories are then provided as in-context examples in the prompt provided to the LLM agent, allowing the trajectories to be used as a demonstration of how to solve a problem. A full example of a prompt—with three in-context examples—used for a ReAct agent on HotpotQA is provided below.

Question: Musician and satirist Allie Goertz wrote a song about the "The Simpsons" character Milhouse, who Matt Groening named after who?

Thought 1: The question simplifies to "The Simpsons" character Milhouse is named after who. I only need to search Milhouse and find who it is named after.

Action 1: Search[Milhouse]

Observation 1: Milhouse Mussolini Van Houten is a recurring character in the Fox animated television series The Simpsons voiced by Pamela Hayden and created by Matt Groening.

Thought 2: The paragraph does not tell who Milhouse is named after, maybe I can look up "named after".

Action 2: Lookup[named after]

Observation 2: (Result 1 / 1) Milhouse was named after U.S. president Richard Nixon, whose middle name was Milhous.

Thought 3: Milhouse was named after U.S. president Richard Nixon, so the answer is Richard Nixon.

Action 3: Finish[Richard Nixon]

Question: Which documentary is about Finnish rock groups, Adam Clayton Powell or The Saimaa Gesture?

Thought 1: I need to search Adam Clayton Powell and The Saimaa Gesture, and find which documentary is about Finnish rock groups.

Action 1: Search[Adam Clayton Powell]

Observation 1: Could not find [Adam Clayton Powell]. Similar: [’Adam Clayton Powell III’, ’Seventh Avenue (Manhattan)’, ’Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building’, ’Isabel Washington Powell’, ’Adam Powell’, ’Adam Clayton Powell (film)’, ’Giancarlo Esposito’].

Thought 2: To find the documentary, I can search Adam Clayton Powell (film).

Action 2: Search[Adam Clayton Powell (film)]

Observation 2: Adam Clayton Powell is a 1989 American documentary film directed by Richard Kilberg. The film is about the rise and fall of influential African-American politician Adam Clayton Powell Jr.[3][4] It was later aired as part of the PBS series The American Experience.

Thought 3: Adam Clayton Powell (film) is a documentary about an African-American politician, not Finnish rock groups. So the documentary about Finnish rock groups must instead be The Saimaa Gesture.

Action 3: Finish[The Saimaa Gesture]

Question: What profession does Nicholas Ray and Elia Kazan have in common?

Thought 1: I need to search Nicholas Ray and Elia Kazan, find their professions, then find the profession they have in common.

Action 1: Search[Nicholas Ray]

Observation 1: Nicholas Ray (born Raymond Nicholas Kienzle Jr., August 7, 1911 - June 16, 1979) was an American film director, screenwriter, and actor best known for the 1955 film Rebel Without a Cause.

Thought 2: Professions of Nicholas Ray are director, screenwriter, and actor. I need to search Elia Kazan next and find his professions.

Action 2: Search[Elia Kazan]

Observation 2: Elia Kazan was an American film and theatre director, producer, screenwriter and actor.

Thought 3: Professions of Elia Kazan are director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. So profession Nicholas Ray and Elia Kazan have in common is director, screenwriter, and actor.

Action 3: Finish[director, screenwriter, actor]

Question: Which magazine was started first Arthur’s Magazine or First for Women?In this example, the ReAct agent is explicitly prompted to output a thought prior to every concrete action that it takes. Unlike a traditional LLM, the ReAct agent does not produce a single output per prompt. Rather, the agent generates output sequentially as follows:

Selects an action to perform (either a concrete action or a thought).

Gets feedback from the environment based on this action (e.g., the information retrieved from a search query).

Continues on to the next action with this new context.

Eventually, the terminal action is reached, triggering the end of the problem solving process; see below. This stateful, sequential problem solving approach is characteristic of agents and helps to distinguish them from standard LLMs.

Decision making. The setup for ReAct on decision making tasks in very similar to that of knowledge-intensive reasoning tasks. For both decision making tasks, humans manually annotate several reasoning trajectories that are used as in-context examples for the ReAct agent. Unlike knowledge-intensive reasoning tasks, however, the thought patterns used by ReAct for decision making tasks are sparse—the model is prompted to use discretion in determining when and how it should think. Additionally, the ReAct agent is provided with a wider variety of tools and actions to use for the WebShop dataset; e.g., search, filter, choose a product, choose product attributes, buy a product and more. This application serves as a good test of ReAct when interacting with a more complex environment.

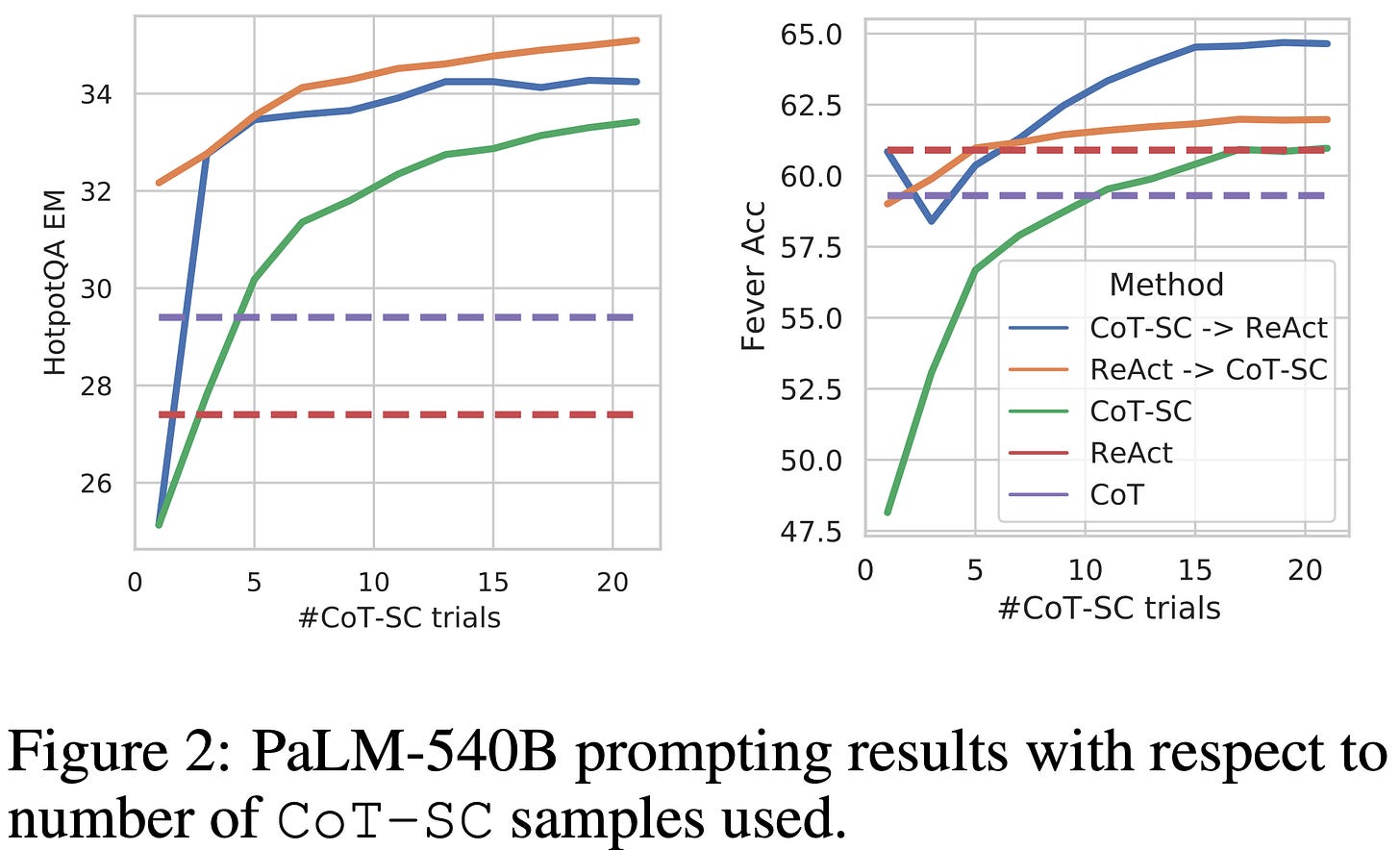

Does ReAct perform well? The ReAct agents described above are compared to several baselines:

Prompting: few-shot prompt that removes thoughts, actions and observations from example trajectories, leaving only questions and answers.

CoT prompting: same as above, but the model is prompted to produce a chain of thought before outputting a final solution4.

Act (action-only): removes thoughts from ReAct trajectories, leaving only observations and actions.

Imitation: agents trained via imitation and / or reinforcement learning to mimic human reasoning trajectories (e.g., BUTLER).

As shown below, the ReAct framework consistently outperforms the Act setup, revealing that the ability of an agent to think as it acts is incredibly important. Going further, we see that CoT prompting is a strong baseline that outperforms ReAct in some cases but struggles in scenarios where the LLM is prone to hallucination—ReAct is able to leverage external sources of information to avoid hallucinating in these cases. Finally, we see that there is much room to improve the performance of ReAct agents. In fact, the agents explored in [1] are quite brittle; e.g., authors note that simply retrieving non-informative information can lead to failure.

ReAct + CoT. ReAct is factual and grounded in its approach to solving problems. Although CoT prompting may suffer from hallucinated facts due to not being grounded in external knowledge, this approach still excels at formulating a structure for solving complex reasoning tasks. ReAct imposes a strict structure of observations, thoughts and actions onto the agent’s reasoning trajectory, while CoT has more flexibility in formulating the reasoning process.

To reap the benefits of both approaches5, we can toggle between them! For example, we can default to CoT prompting if ReAct fails to return an answer after N steps (i.e., ReAct → CoT) or take several CoT samples and use ReAct if disagreement exists among the answers (i.e., CoT → ReAct). As shown above, such a backoff approach—in either direction—boosts the agent’s problem solving capabilities.

Prior Attempts at Agents

Although ReAct was (arguably) the first lasting framework to be proposed for AI agents, there were a variety of impactful papers and ideas previously proposed within the agents space. Here, we will quickly outline some of these key proposals and how they compare, allowing us to understand how the ReAct framework builds upon prior work to create a more useful and popular framework.

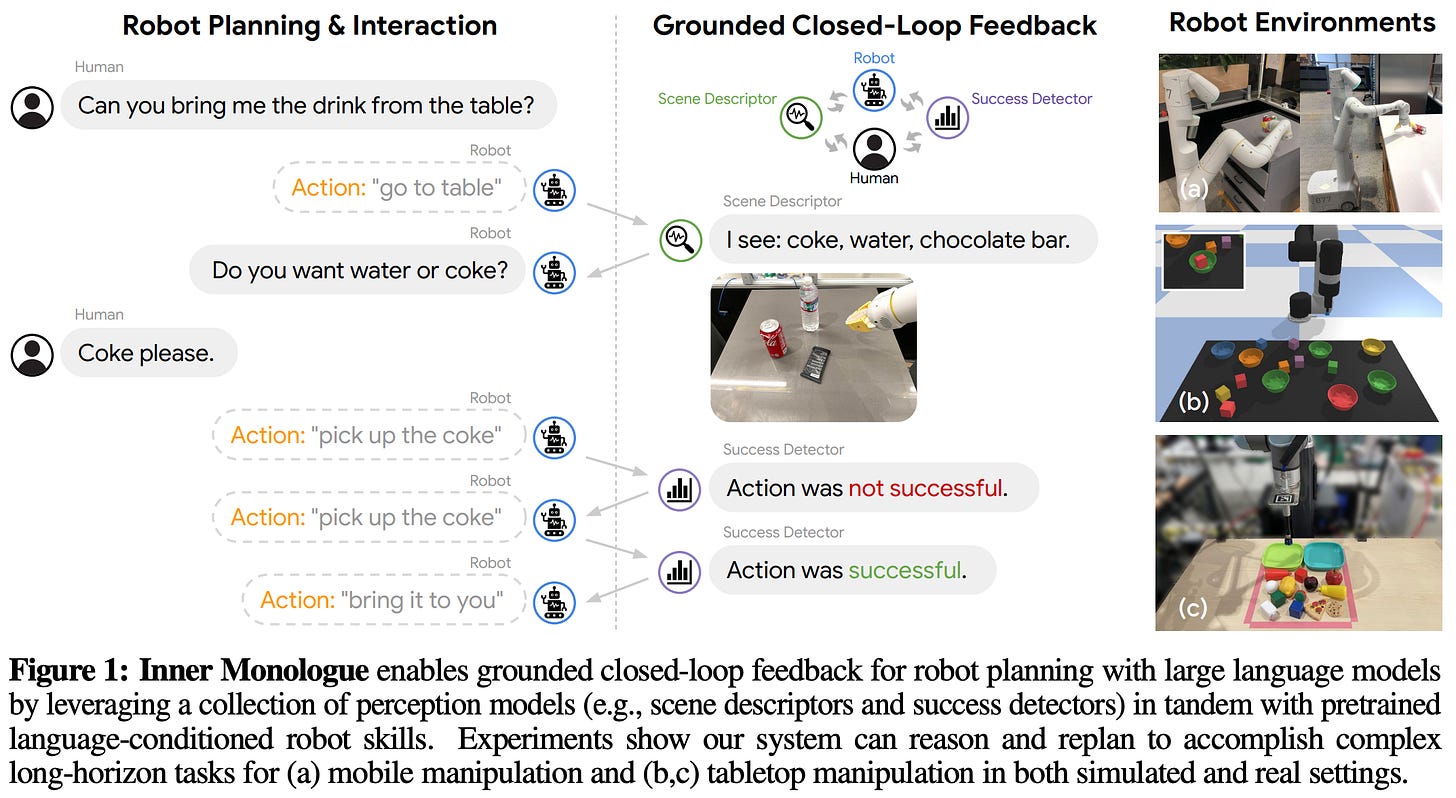

Inner monologue (IM) [10] was one of the most comparable works to ReAct and is applied to planning in a robotics setting. As shown above, IM integrates an LLM with several domain-specific feedback mechanisms; e.g., scene descriptors or success detectors. Somewhat similarly to ReAct, the LLM is used to generate a plan and monitor the solution of a task—like picking up an object—by iteratively acting, thinking and receiving feedback from the external environment.

“We investigate to what extent LLMs used in embodied contexts can reason over sources of feedback provided through natural language… We propose that by leveraging environment feedback, LLMs are able to form an inner monologue that allows them to more richly process and plan in robotic control scenarios.” - from [10]

IM demonstrates the feasibility of leveraging LLMs as a general tool for problem solving in domains beyond natural language. Relative to ReAct, however, the ability of the LLM to “think” within IM is limited—the model can only observe feedback from the environment and decide what needs to be done next. ReAct solves this problem by empowering the agent to output extensive, free-form thoughts.

LLMs for interactive decision making (LID) [14] uses language as a general medium for planning and action by proposing a language-based framework for solving sequential problems. We can formulate the context and action space for a wide variety of tasks as a sequence of tokens, thus converting arbitrary tasks into a standardized format that is LLM-compatible. Then, this data can be ingested by an LLM, allowing powerful foundation models to incorporate feedback from the environment and make decisions; see above. In [14], authors finetune LID using imitation learning to correctly predict actions across a variety of domains.

WebGPT [11] explores integrating an LLM (GPT-3) with a text-based web browser to more effectively answer questions. This work is any early pioneer of open-ended tool use and teaches the LLM how to openly search and navigate the web. However, WebGPT is explicitly finetuned over a large dataset of task solutions from humans (i.e., behavior cloning or imitation learning). Therefore, this system—despite being very forward-looking and effective (i.e., produces answers preferred to those of a human in >50% of cases)—requires a large amount of human intervention. Nonetheless, finetuning LLM agents with human feedback is a hot research topic even today, and WebGPT is a foundational work in this space.

Inspired by the broad capabilities of LLMs, Gato [12] is a single “generalist” agent that is capable of acting across many modalities, tasks and domains. For example, Gato is used for playing Atari, captioning images, manipulating robotic arms and more. As described in the report, Gato is capable of “deciding based on its context whether to output text, joint torques, button presses, or other tokens.” This model truly works towards the goal of creating an autonomous system that can solve almost any problem. Similarly to WebGPT, however, Gato is trained via an imitation learning approach that collects a massive dataset of context and actions—all represented as flat sequences of tokens—across many problem scenarios.

Reasoning via Planning (RAP) [13] aims to endow LLMs with a better world model—or an understanding of the environment in which they act and the rewards that come from it—with the goal of improving the LLM’s ability to plan solutions to complex, multi-step problems. In particular, the LLM is used to build a reasoning tree that can be explored via Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to find a solution that achieves high reward. Here, the LLM itself is also used to evaluate solutions—the LLM serves as both an agent and a world model in RAP!

“The LLM (as agent) incrementally builds a reasoning tree under the guidance of the LLM (as world model) and rewards, and efficiently obtains a high-reward reasoning path with a proper balance between exploration vs. exploitation.” - from [13]

RAP is a useful and effective framework, but it is applied purely to text-based reasoning problems in [13]—it is not a general problem-solving framework like ReAct. There are many such works that bear a high level of resemblance to agent systems but are applied mostly to improving LLM reasoning capabilities:

Selection-Inference improves LLM reasoning capabilities by separating the problem solving process into alternating steps of selection (or planning) and solving. A similar approach is pioneered by Creswell et al.

Re2 is a prompting strategy that improves LLM reasoning capabilities by asking the LLM to re-read the question prior to deriving an answer.

LLM-Augmenter combines an LLM with databases or sources of domain-specific information that provide useful external knowledge to the LLM, thus improving groundedness in question-answering tasks.

For a more complete survey of research on the intersection of agents and reasoning for LLMs (and much more), see this incredible writeup.

What is an “agent”?

“The simplest way to view the starting points for language model-based agents is any tool-use language model. The spectrum of agents increases in complexity from here.” - Nathan Lambert

Despite their popularity in the industry, agents do not have a clear definition—there is a lot of discussion about what qualifies as an “agent”. Lack of clarity on the definition of agents arises from the fact that we encounter a variety of agents in today’s world that lie on a wide spectrum of complexity. At a high level, the functionality of an agent may appear similar to that of an LLM in some cases, but an agent typically has a wider scope of strategies and tools available for solving a problem. Using the information we have learned so far, we will now create a framework for understanding the spectrum of capabilities an AI agent may possess, as well as how these capabilities differ from a standard LLM.

From LLMs to Agents

We have learned about a variety of concepts in this overview, including i) standard LLMs, ii) tool usage, iii) reasoning models and iv) autonomous systems for problem solving. Starting with the standard definition of an LLM, we will now explain how each of these ideas can be used to build upon the standard LLM’s capabilities, creating a system that is more agentic in nature.

[Level 0] Standard LLMs. As a starting point, we can consider the standard setup for an LLM (depicted above), which receives a textual prompt as input and generates a textual response as output. To solve problems, this system purely relies upon the internal knowledge base of the LLM without introducing external systems or imposing any structure upon the problem-solving process. To solve more complex reasoning problems, we may also use a reasoning-style LLM or a CoT prompting approach to elicit a reasoning trajectory; see below.

[Level 1] Tool usage. Relying upon an LLM’s internal knowledge base is risky—LLMs have a fixed knowledge cutoff date and a tendency to hallucinate. To mitigate this problem, we can teach an LLM how to make API calls for the purpose of retrieving useful information and solving sub-tasks with specialized tools. Using this approach, the LLM can more robustly solve problems by delegating the solution of sub-tasks to more specialized systems; see below.

[Level 2] Decomposing problems. Expecting an LLM to solve a complex problem in a single step may be unreasonable. Instead, we can create a framework that plans how a problem should be solved and iteratively derives a solution. Such an LLM system can be handcrafted; e.g., by chaining multiple prompts or executing several prompts in parallel and aggregating their results. Alternatively, we can avoid this manual effort by using a framework like ReAct that relies upon an LLM to sequentially derive and execute a problem-solving strategy; see below.

Of course, the problem of decomposing and solving complex problems with an LLM is intricately related to tool usage and reasoning. The LLM may rely upon various tools throughout the problem solving process, and reasoning capabilities are essential for formulating detailed and correct plans for solving a problem. Going further, this LLM-centric approach to problem solving introduces the notion of control flow to inference with an LLM—the agent’s output is sequentially built as it statefully moves through a sequence of problem-solving steps.

[Level 3] Increasing autonomy. The above framework outlines most key functionalities of AI agents today. However, we can also make such a system more capable by providing it with a greater level of autonomy. For example, we can include within the agent’s action space the ability to take concrete actions (e.g., buying an item, sending an email or opening a pull request) on our behalf.

“An agent is anything that can perceive its environment and act upon that environment… This means that an agent is characterized by the environment it operates in and the set of actions it can perform.” - Chip Huyen

So far, the agents we have outlined always take a prompt from a human user as input. When given this prompt, they begin the process of thinking, acting and formulating an appropriate response. In other words, these agents only take action when triggered by a prompt from a human user. However, this does not have to be the case! We can build agents that continuously operate in the background. For example, a lot of research has been done on open-ended computer use agents, and OpenAI recently announced Codex—a cloud-based software engineering agent that can work on many tasks in parallel and even make PRs to codebases on its own.

AI agent spectrum. Combining all of the concepts we have discussed throughout this overview, we could create an agent system that:

Runs asynchronously without any human input.

Uses reasoning LLMs to formulate plans for solving complex tasks.

Uses a standard LLM to produce basic thoughts or synthesize information.

Takes actions in the external world (e.g., booking a plane ticket or adding an event to our calendar) on our behalf.

Retrieves up-to-date info via the Google search API (or any other tool).

Each style of LLM—as well as any other tool or model—has both strengths and weaknesses. These components provide agent systems with many capabilities that are useful for various aspects of problem solving. The crux of agent systems is orchestrating these components in a way that is seamless and reliable. However, agents lie on a spectrum and may or may not use all of these functionalities; e.g., the system described above, a basic tool-use LLM and a chain of prompts for solving a particular class of problems all fall under the umbrella of an agent system.

The Future of AI Agents

Although AI agents are incredibly popular, work in this space—both from a research and application perspective—is nascent. As we have learned, agents operate via a sequential problem solving process. If any step in this process goes wrong, then the agent is likely to fail. As such, reliability is a prerequisite for building effective agents in complex environments. In other words, building robust agent systems will require creating LLMs with more nines of reliability; see below.

“Last year, you said the thing that was holding [agents] back was the extra nines of reliability… that's the way you would still describe the way in which these software agents aren't able to do a full day of work, but are able to help you out with a couple minutes.” - Dwarkesh Podcast

Many agents today are (arguably) brittle due to a lack of reliability. However, progress is being made quickly, both on LLMs in general (i.e., better reasoning and new generations of models) and agents in particular. Recent research has focused especially on effectively evaluating agents, creating multi-agent systems and finetuning agent systems to improve reliability in specialized domains. Given the pace of research in this area, we are likely to see a significant increase in the capabilities and generality of these agent systems in the near future.

New to the newsletter?

Hi! I’m Cameron R. Wolfe, Deep Learning Ph.D. and Senior Research Scientist at Netflix. This is the Deep (Learning) Focus newsletter, where I help readers better understand important topics in AI research. The newsletter will always be free and open to read. If you like the newsletter, please subscribe, consider a paid subscription, share it, or follow me on X and LinkedIn!

Bibliography

[1] Yao, Shunyu, et al. "React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models." International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). 2023.

[2] Schick, Timo, et al. "Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023): 68539-68551.

[3] Thoppilan, Romal, et al. "Lamda: Language models for dialog applications." arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.08239 (2022).

[4] Shen, Yongliang, et al. "Hugginggpt: Solving ai tasks with chatgpt and its friends in hugging face." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023): 38154-38180.

[5] Patil, Shishir G., et al. "Gorilla: Large language model connected with massive apis." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (2024): 126544-126565.

[6] Wei, Jason, et al. "Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models." Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022): 24824-24837.

[7] Kojima, Takeshi, et al. "Large language models are zero-shot reasoners." Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022): 22199-22213.

[8] Guo, Daya, et al. "Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning." arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948 (2025).

[9] Lambert, Nathan, et al. "T\" ulu 3: Pushing frontiers in open language model post-training." arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.15124 (2024).

[10] Huang, Wenlong, et al. "Inner monologue: Embodied reasoning through planning with language models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.05608 (2022).

[11] Nakano, Reiichiro, et al. "Webgpt: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback." arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.09332 (2021).

[12] Reed, Scott, et al. "A generalist agent." arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.06175 (2022).

[13] Hao, Shibo, et al. "Reasoning with language model is planning with world model." arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14992 (2023).

[14] Li, Shuang, et al. "Pre-trained language models for interactive decision-making." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (2022): 31199-31212.

[15] Anthropic. “Introducing the Model Context Protocol” https://www.anthropic.com/news/model-context-protocol (2024).

In the context of reasoning models, these chains of thought are also referred to as reasoning trajectories or traces.

This is quite similar to the definition of a policy in reinforcement learning (RL); see here for details. In both cases, the policy is implemented as a language model and produces an action as output. The main difference between the agent and RL definition of a policy is the policy’s input. For agents, the input is the current observation. For RL, the the policy’s input is the current state of the environment.

CoT prompting can also be extended with self-consistency with a majority vote to further improve performance.

Notably, ReAct (or any other agentic framework) is not guaranteed to outperform standard CoT prompting! The relative performance of these techniques is highly related to the complexity of problems being solved—CoT prompting performs very well in cases where hallucination is unlikely to be a problem for the LLM being used.

As always, a great and easy to understand write-up. I am subscribed to a lot of publishers on Substack, but you are definitely one of my favourites! Please keep on writing these amazing posts.

This was really long awaited. Tysm ❤️